Daniyal Mahmood Ahmad, Al Hakam

A fragmented world

Loyalty to one’s state is an important Islamic tenet – one which might have been overlooked when Sharif Hussein led his rebellion, known as the Arab Revolt (1916-1918), which contributed towards the collapse of an already declining empire, the resulting fragmentation of Muslim unity and loss of the Caliphate in the political sphere.

This disunity, which was partially sown during the revolt, has had lasting repercussions, leaving the Muslim world fractured and extremely vulnerable to external interventions.

Caliph-less

It is no secret that Trump has his eyes set on Gaza, whilst the Muslim world helplessly looks on at the fleeting dream of an independent Palestinian state. This is a stark contrast to when a Sultan-Caliph would simply turn away powerful and influential people who had set their eyes on Palestine over a century ago.

However, the Muslim world has been without a political Caliphate for over 100 years now, since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk abolished the Ottoman Caliphate on 3 March 1924. Many factors led to the decline and fall of the empire, one of which was Sharif Hussein’s revolt against the Ottoman state.

Guardians of the two holy shrines

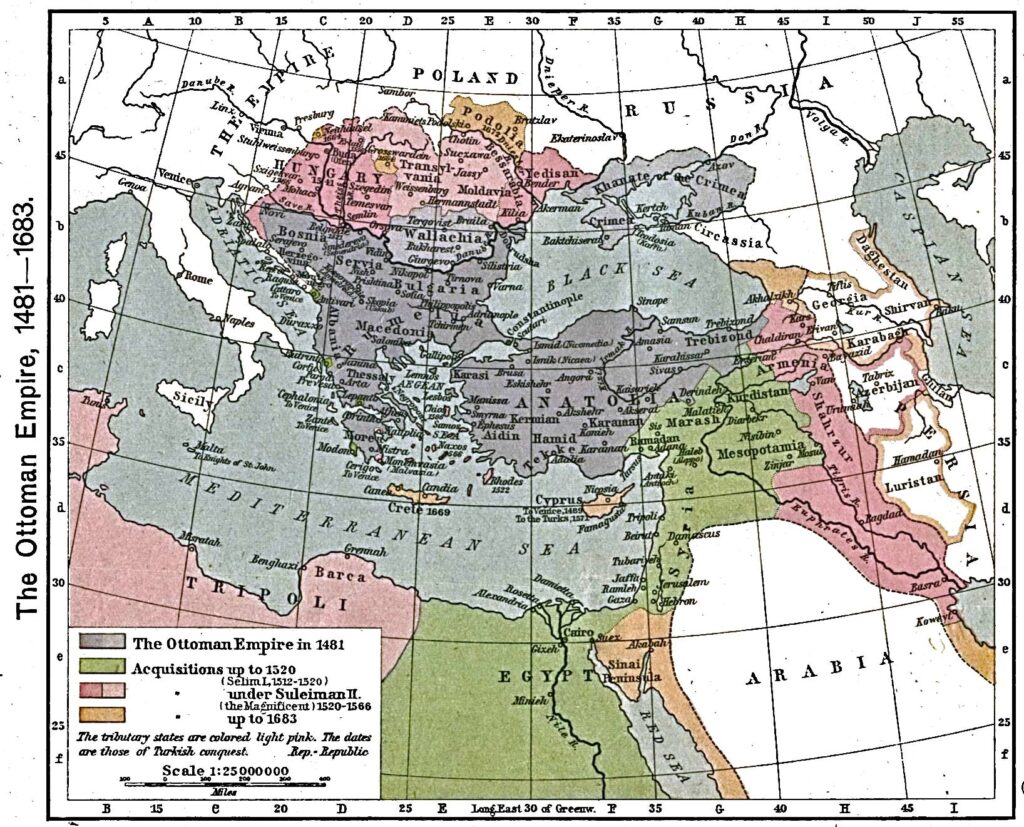

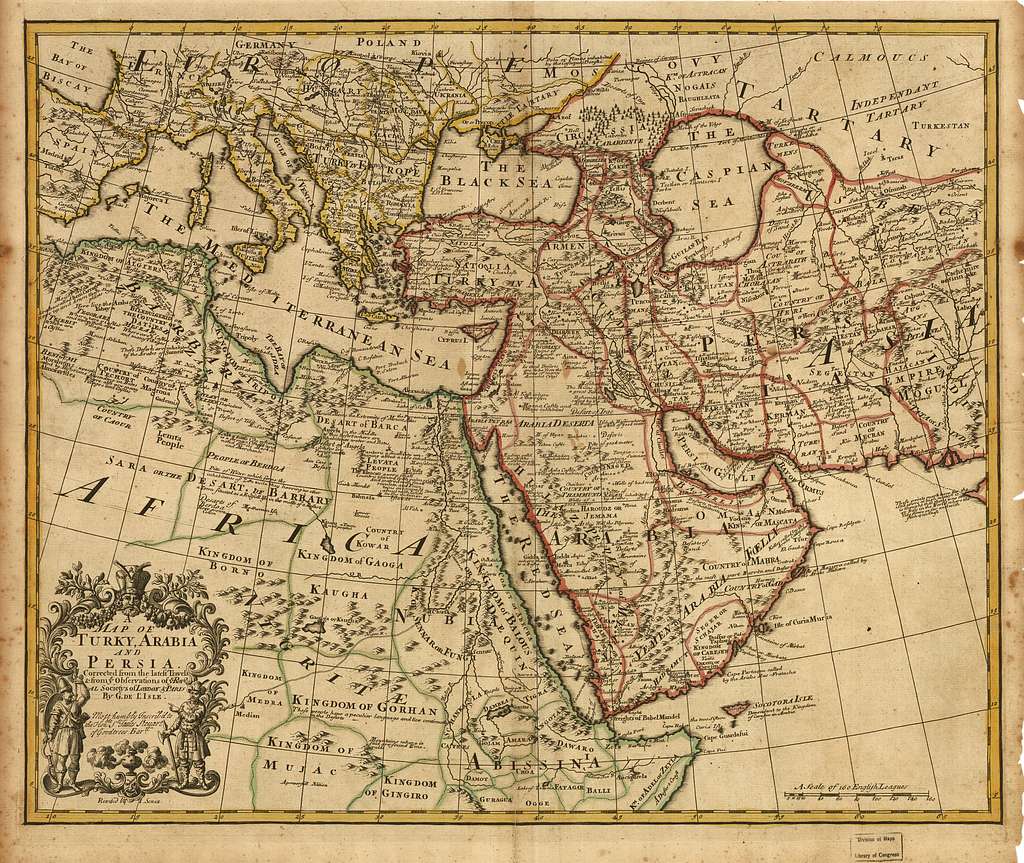

The Ottoman Empire was vast. Throughout its 7-century history, at various times it covered the lands of modern-day Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, Libya, the Balkans and many more thousands of square miles of land. The most important of these, to Muslims, would have been the Hejaz region of modern day Saudi Arabia, which consists of the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

The Sultan – or Caliph, as Sultan Selim I additionally styled himself after the conquest of the Hejaz, and every Sultan after him as well – usually held immense, if not absolute power. One of these was Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ruled absolute from 1876 to 1909.

Zionist aspirations

In the late 19th century, Theodore Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, expressed his desire to approach the Sultan-Caliph with an offer to purchase land in Palestine:

“Supposing His Majesty the Sultan were to give us Palestine, we could in return pledge ourselves to regulate the whole

finances of Turkey.” (Theodore Herzl, The Jewish State, 1917, p. 12)

According to some reports, he even approached the Sultan at least twice with a proposal to purchase land in Palestine for Jewish settlement. (Ibid. pp. vi-vii)

The Sultan’s supposed response to this offer has been immortalised in variations of the following words:

“I cannot sell even a foot of land, for it does not belong to me but to my people. My people have won this Empire by fighting for it with their blood and have fertilised it with their blood. We will again cover it with our blood before we allow it to be wrested away from us.”

He stayed true to this statement throughout his reign. This, along with other efforts to unite and lead the Muslim world under his Caliphate resulted in the era of Abdul Hamid II’s reign to be described as the “Era of Pan-Islamism”. (Muhammad Harb, Sultan Abdul Hamid II, The Last Great Ottoman Sultan, p. 208)

With this stance, he made himself an enemy of Herzl and the Zionists, along with the already extensive list of other enemies he had accumulated. Eventually, through various means and factors, the Sultan was deposed and the CUP (Committee of Union and Progress), or Young Turks Movement, took the reins of power, with the new Sultan acting only as a figurehead.

The revolt: Seeds of division

Sharif Hussein was appointed the Emir of Mecca by the Ottomans in 1908. Even before then, anti-Ottoman and nationalistic sentiments were brewing throughout the empire. It was already in decline, and likely would’ve continued to do so after Abdul Hamid II’s reign.

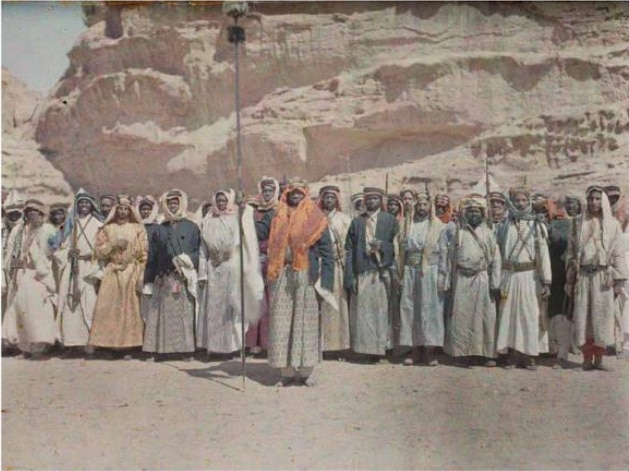

It was only after the CUP took power and joined the First World War on the side of the Entente that Sharif Hussein made his move. In 1916 he initiated a strategy of guerilla warfare against the Ottomans, which Lawrence of Arabia would later write an analysis of, who played a crucial role in instigating and facilitating this rebellion.

The Sharif’s army consisted mainly of the Arabs of the Hejaz, but it was undoubtedly supplemented by Great Britain in various ways. For example, in June 1916, British intelligence officers desperately attempted to recruit Arab prisoners to join the Sharif’s cause through the Viceroy of India. Although 300 prisoners were sent to fight for the Sharif, many declined to fight against the Ottomans out of loyalty. (Mesut Uyar, Ottoman Arab Officers between Nationalism and Loyalty during the First World War, p. 542)

This is an interesting fact as it shows that the Arab revolt cannot be seen in absolute terms of loyalty or disloyalty. It would be an abstract oversimplification to claim that all Arabs betrayed the Ottomans.

The fact remains, however, that certain groups of Muslims betrayed their state – an Islamic state – and sided with Britain, a non-Muslim state. Whatever their reasons and justifications, the irony of this situation might be lost on some.

Promises made, promises broken

Britain went further than just providing military support. It even promised the Sharif an independent Arab Kingdom in event of victory, along with other lofty promises, as the correspondence between the British statesman Sir Henry McMahon and Sharif Hussein shows:

“To his Highness the Sherif Hussein […] We rejoice, moreover, that your Highness and your people are of one opinion – that Arab interests are English interests and English Arab […] our desire for the independence of Arabia and its inhabitants, together with our approval of the Arab Khalifate when it should be proclaimed. We declare once more that His Majesty’s Government would welcome the resumption of the Khalifate by an Arab of true race.” (Sir Henry McMahon, Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, G.C.M.G, His Majesty’s High Commissioner at. Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca, p. 4)

The above correspondence makes one wonder; what’s worse, loyalty to a non-Muslim state which rules over you, or disloyalty to a Muslim state which does? And what would the status of such a caliphate be which depended on the approval of the disbelievers?

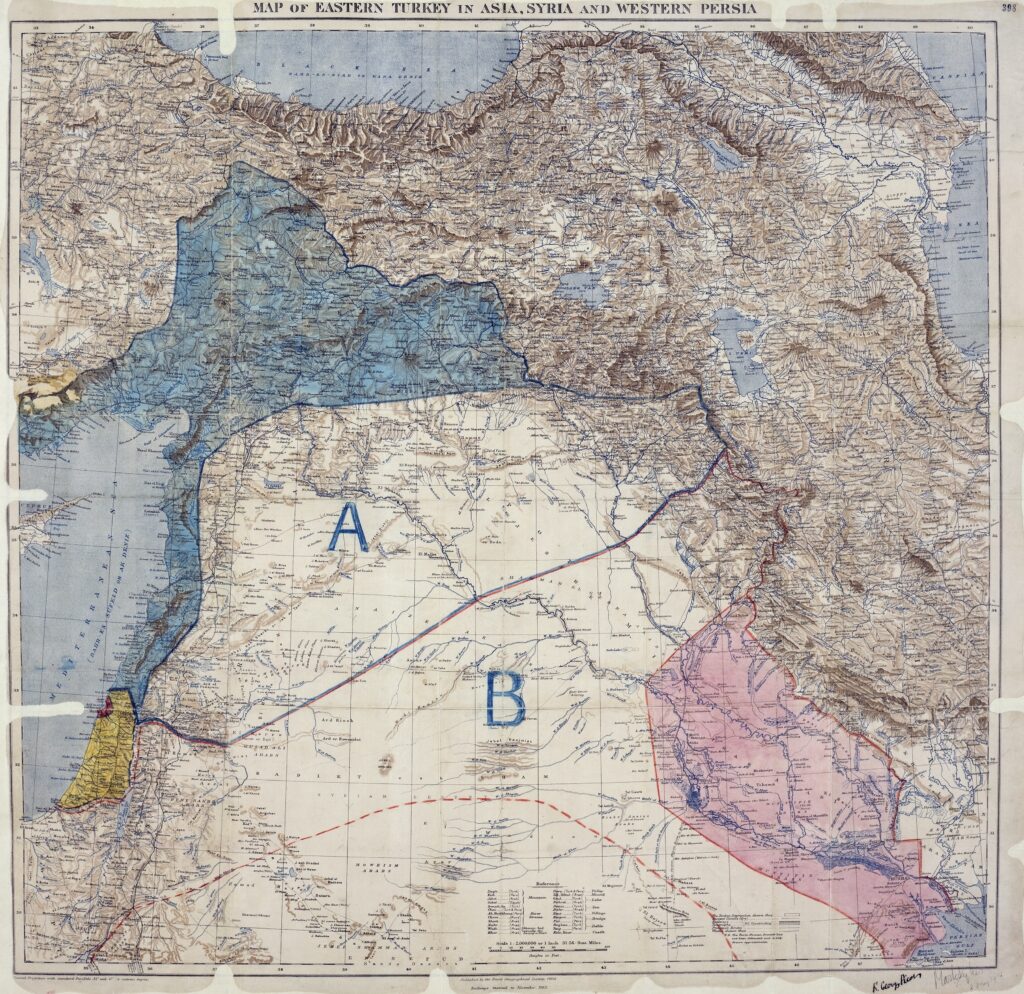

In any case, the British eventually reneged on their promise, and instead of handing over the Arab lands to the Arabs, they carved up the Middle East along with France in the Sykes–Picot Agreement. (Arab Question; Sykes and Georges-Picot, Memorandum, 3 January 1916)

This agreement wasn’t Syke’s only contribution. He was, in fact, the person who designed the flag of resistance for the Arabs, which many modern-day Arab states have taken inspiration from for their national flags. (William Easterly, The White Man’s Burden, 2006, p. 295)

Fall of the Ottomans

With his own Hashemite forces, along with backing from the British military’s Egyptian Expedition Force, Sharif Hussein successfully fought and expelled the Ottoman forces from the Hejaz and surrounding Arab lands. The rebels had captured Damascus by 1918 and declared their independent Arab Kingdom of Syria, which was short-lived due to the Sykes-Picot agreement.

This was a massive blow to the Ottoman Empire. By this time it not only lost its Arab provinces, but also World War I in general, along with the other Entente powers.

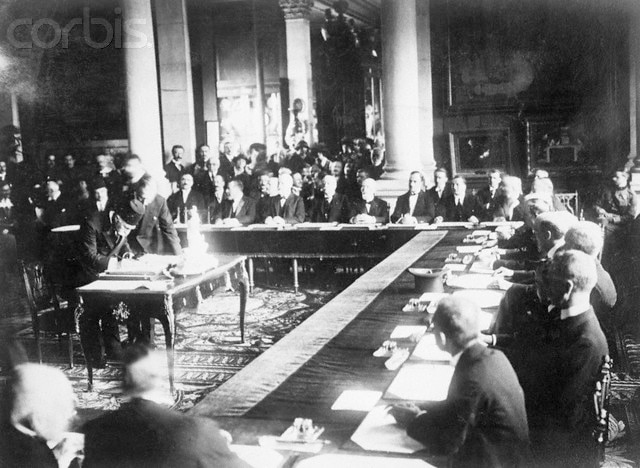

Greatly weakened, Britain, France and other allied nations enforced the signing of the Treaty of Sevres, which would have the allies occupy the former territories of the empire, including the Turkish heartland of Anatolia as well as Palestine. Although completely and utterly defeated, the Ottoman Empire remained intact in name, whilst being occupied by foreign powers. (Eugene Rogan, The Fall of Ottomans, p. 397)

This blow to the Muslim world had been intended all along, as David Fromkin states:

“[..] .the assumption that Europeans had shared about the Middle East for centuries: that its post-Ottoman political destinies would be taken in hand by one or more of the European powers.” (David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, 1989, pp. 76)

Eventually, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk led his rebel forces to liberate the Turkish mainland from the allies, and after successfully doing so, finalised the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, deposing the Sultan and establishing the Republic of Turkey. (Caroline Finkel, The History of the Ottoman Empire, Osman’s Dream, p. 1)

End of the Caliphate

Throughout this turmoil, perhaps the deepest wound that the Muslim world suffered on the political stage was the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate.

The Times reported on 3 March 1924:

“The Motion for the abolition of the Caliphate was passed in the Grand National Assembly to-day after a stormy debate.”

Abdulmecid II, the last Caliph of the Ottoman dynasty was deposed and exiled.

This was the last generally recognised political caliphate in the Islamic world. Accompanied by the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate signified the breakup of a unified Islamic authority and entity that could have been able to potentially protect not just the rights and interests of Palestine as it had done in the past, but also much of the rest of the Muslim world. The Muslim world, it seemed, was fragmented and leaderless.

Islamic perspective on unity & loyalty to state

This situation could have been avoidable if Islamic injunctions were properly followed. Islamic literature is replete with teachings on unity and loyalty to the state.

The Holy Quran mentions that Muslims should hold fast to the rope of Allah and not to become divided (Surah Al-e-’Imran, Ch. 3:104). This is a clear instruction and call for unity among Muslims.

The Holy Prophetsa expounded further on this concept in one of his narrations:

مَثَلُ الْمُؤْمِنِينَ فِي تَوَادِّهِمْ وَتَرَاحُمِهِمْ وَتَعَاطُفِهِمْ مَثَلُ الْجَسَدِ إِذَا اشْتَكَى مِنْهُ عُضْوٌ تَدَاعَى لَهُ سَائِرُ الْجَسَدِ بِالسَّهَرِ وَالْحُمَّى

“The similitude of believers in regard to mutual love, affection, fellow-feeling is that of one body; when any limb of it aches, the whole body aches, because of sleeplessness and fever.” (Sahih Muslim, Hadith 2586)

With regard to loyalty to the state in which a Muslim lives, the Holy Quran categorically states:

يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوٓاْ أَطِيعُواْ ٱللَّهَ وَأَطِيعُواْ ٱلرَّسُولَ وَأُوْلِي ٱلۡأَمۡرِ مِنكُمۡ

“O ye who believe! obey Allah, and obey [His] Messenger and those who are in authority among you.” (Surah an-Nisa’, Ch.4: V.60)

The Holy Prophet Muhammadsa further reinforces this injunction:

مَنْ أَطَاعَنِي فَقَدْ أَطَاعَ اللَّهَ، وَمَنْ عَصَانِي فَقَدْ عَصَى اللَّهَ، وَمَنْ أَطَاعَ أَمِيرِي فَقَدْ أَطَاعَنِي، وَمَنْ عَصَى أَمِيرِي فَقَدْ عَصَانِي

“Whoever obeys me, obeys Allah, and whoever disobeys me, disobeys Allah, and whoever obeys the ruler I appoint, obeys me, and whoever disobeys him, disobeys me.” (Sahih al-Bukhari, Hadith 7137)

The above verses and ahadith provide us with the valuable insight that Muslims, as an entity, can derive immense benefit in unity and loyalty. The natural conclusion would be that disunity and disloyalty would result in harm and damage, as can be deduced from the events mentioned in this article.

Power of true Caliphate

The factors which led to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Caliphate and the current turmoil that the fragmented Muslim world finds itself are many.

Depending on perspective, the Arab revolt led by Sharif Hussein might be to blame. Whilst others may consider Mustafa Kemal Ataturk to have been the final nail in the coffin. Yet again, some might argue that it was the interference of the Western powers that led to the fragmentation of the Muslim world.

The abolition of the political Caliphate was definitely a deep wound, even though by that time the characters and acts of the caliphs didn’t resemble those of the four righteous Caliphs.

There is no doubt, however, that true Khilafat – as promised by Allah the Almighty in the Holy Quran in Surah an-Nur, Ch.24: V.56 – would have provided the Muslim world with the right guidance to navigate the stormy seas of the modern-day political landscape.

Additionally, perhaps a stronger counterbalance to external interference – past and present – could have been provided by stronger Muslim unity, which would have been the natural result of loyal obedience to Khilafat.

Conclusion

With the helpless situation of the Muslim world and its leaders in the face of powerful entities and people such as Trump and his plans for Gaza, it’s worth reflecting whether unity amongst the Muslim world and loyalty to the state and people in authority, such as the caliph, might have provided a more robust defence of the interests of the Muslim world today.

With the above in mind, and now that the Muslim world has entered the second century of no political caliphate, it can learn a powerful lesson from the words of Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, the second Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community:

“When the Turks ruled over the Arabs, we supported the Turks. When Sharif Hussein became the ruler, people strongly opposed him, but we said that it was not appropriate to spread disorder and conflict. The person whom God has made a ruler should be accepted so that the continuous unrest in Arabia may come to an end.

“After that, when the Najdis took over the government, despite the fact that people raised much commotion, accusing them of demolishing tombstones and disrespecting the Sha’airillah, we supported Sultan Ibn Saud solely because we did not approve of frequent battles in the sacred city of Makkah […] We do not wish for unrest in these regions.” (Khutbat-e-Mahmud, Vol. 16, pp. 549-550)