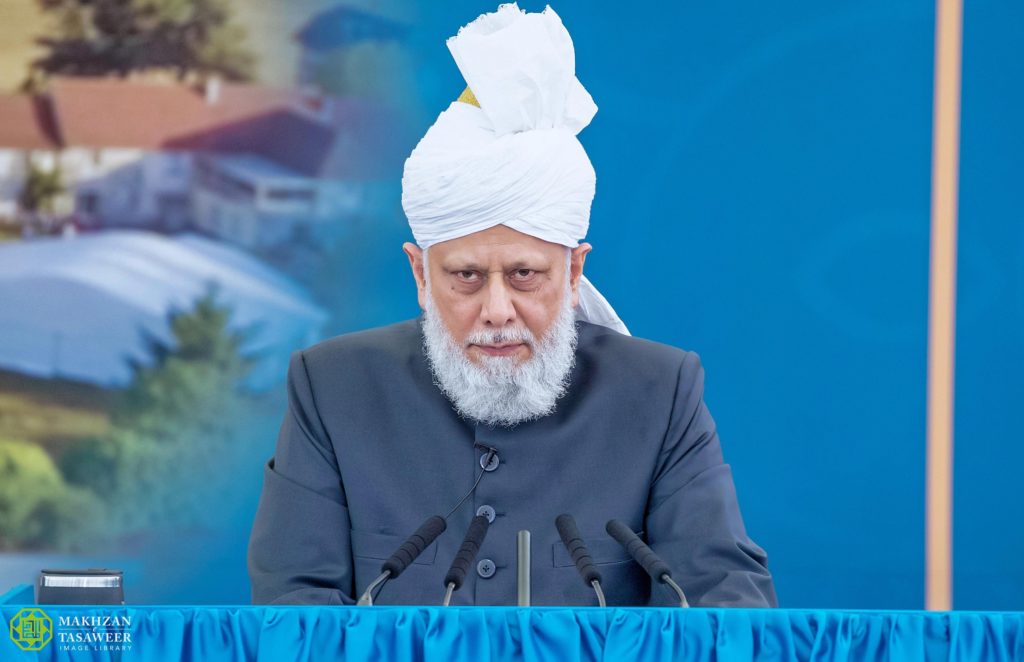

Friday Sermon

4 October 2019

Jalsa Salana France 2019

After reciting the Tashahud, Ta‘awuz, and Surah al-Fatihah, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa stated:

Today, by the grace of Allah the Almighty, your Jalsa Salana [annual convention] is going to commence. The Promised Messiahas has described the Jalsa as “a purely religious gathering”. Thus, it should be clear to every participant of the Jalsa that we have gathered here today to make progress and advancement in terms of religion, knowledge and spirituality. We have gathered here today, and shall remain here over the next three days, reflecting and deeply pondering as to how we can improve our conditions in terms of faith, knowledge and spirituality. If one does not adopt this mindset, then there is no benefit in coming here.

In today’s age, where the world is becoming unmindful of God Almighty, followers of all religions are moving away from their religions. The figures that come out annually indicate that a large number of people express disbelief in the existence of God Almighty. Even the condition of the Muslims indicates that they are Muslims in name only and that materialism has taken over. We claim to believe in the Imam of the Age, sent by Allah the Almighty in this era in accordance with the prophecy of the Holy Prophetsa to revive the faith and while having made this covenant that we will also help fulfil the mission of the Promised Messiah and Mahdias. Therefore, in light of this if we do not pay attention to improving our conditions, then our claim to have come into the Bai‘at of the Promised Messiahas is just a hollow expression. It will be empty of any spirit and our covenant of Bai‘at is merely a covenant in name and we are failing to fulfil it and our attending this Jalsa equals to attending a worldly festival. Thus, every Ahmadi should greatly reflect upon this. There is a need to pay attention towards assessing your conditions with great concern for if we are guilty of having such a mindset, then [all of this] is of no benefit.

If we analyse ourselves, while keeping in view the objectives of Jalsa Salana that the Promised Messiahas has stipulated for us, then we will not only be fulfilling the purpose of these three days, but we will also become recipients of the prayers of the Promised Messiahas that he offered in favour of the attendees of Jalsa; we will beautify our life in this world and the Hereafter by making [those objectives] a permanent part of our lives; we will not only be improving our own conditions, but our effort to seek good deeds and our acting upon them will also make our next generations firm in faith, bring them closer to God Almighty and make them recipients of the blessings of Allah the Almighty. In an age where the world is distancing itself from God Almighty and religion, our progeny will come closer to God Almighty and will become a means to bring the world closer to God Almighty.

Thus, if we wish to fulfil the covenant of Bai‘at and save our progeny, then we need to be ever mindful of the objectives of the Jalsa. We need to observe these three days with the firm resolve that these objectives will now continue to be part of our lives. While elucidating the objectives of Jalsa, the Promised Messiahas said that the attendees of the Jalsa should be concerned about their [wellbeing in the] Hereafter. This Jalsa is being held so that the attendees, being in this environment, should develop a concern about their Hereafter, they should inculcate the fear of Allah, righteousness, kind-heartedness, an atmosphere of mutual love and brotherhood, humbleness, humility and that they should establish themselves upon truthfulness and become active in the service of faith. (Shahadatul Quran, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 6, p. 394)

Thus, this is the purpose of our gathering here today. In relation to the words of the Promised Messiahas, every follower, whether a man or a woman, old or young, should be worried about their Hereafter to the extent that worldly things should amount to nothing compared to it. While living in this material world, this is a monumental task and a huge challenge, and in order to accomplish this, we need to undertake a great Jihad. One can only be concerned about one’s Hereafter if one truly believes in the existence of God Almighty and has firm faith that this world is only for a few years.

One can, at most, live for 80 years or 90 years or a maximum of around 100 years, but most do not even reach such an age and pass away much earlier. However, what happens is that we tend to sacrifice the permanent life for the sake of this temporary life and yet, despite this, worldly people consider themselves to be great and wise. Thus, a believer ought to not act in this manner. Only then can he be considered a true believer.

One should instil the fear of God Almighty in their hearts and the love of Allah the Almighty should supersede all other worldly affections. One should not fear Allah the Almighty because they will be punished in the next life, rather they do so because they do not wish for their beloved God to be displeased with them. Only when these sentiments of love develop does a person strive to act in accordance with the commandments of God the Almighty. Every deed of such a person is performed in consideration of the Hereafter.

A person is certain that it is God Alone Who grants him the means for his provisions. It is only God Who blesses him with His rewards. This includes all forms of rewards, worldly as well as spiritual. He believes that if he continues to fulfil the rights of His worship, if he continues to submit himself before God, whilst considering Him to be the Possessor of all powers, he will continue to receive His rewards, Insha-Allah [God willing]. If he continues to live in accordance with His commandments and prohibitions, then he will continue to become the recipient of His blessings. If he continues to fulfil the rights of Allah the Almighty as well as those of His creation, whilst showing complete obedience to Him and whilst maintaining righteousness, God Almighty will be pleased with him. Hence, this mind-set and acting in accordance with it will certainly enable a person to become the recipient of the rewards and blessings of Allah the Almighty in accordance with His promise.

Furthermore, these very people, who have such a mindset, are referred to as those who tread the path of righteousness, that is, those who act in accordance with all of the commandments of Allah the Almighty and whose hearts have softened as God is found within their hearts in each and every moment of their lives. These are the very people, who hold sentiments of love for one another for the sake of God Almighty, that is, their love and brotherhood are not for personal interests, but purely for the sake of God Almighty. Similarly, these are the very people, who tread the path of righteousness and develop modesty. Furthermore, they are not merely modest in front of those, who are higher in status in terms of worldly wealth and stature, rather, they are also modest in front of the poor and the needy. These are the very people, who uphold truthfulness at all times and who believe that saying the right word leads a person to God Almighty and that falsehood leads to Shirk [associating partners with God].

Hence, when a person is mindful of the Hereafter, is fearful of God Almighty, comprehends the reality of righteousness, then how can such a person speak falsehood after having become a believer. Furthermore, those who attain these qualities and comprehend the true spirit of virtues are in fact the ones who are truly active in the service of religion. Otherwise, this service also becomes a superficial means of acquiring personal interests. We observe that there are hundreds of scholars among the Muslims, who seem to be very active for the service of their faith, however in reality they are committing cruelties in the name of religion. They lack righteousness, the fear of God cannot be seen in them and worldly interests are dearer to them than the Hereafter, yet, they speak about the importance of God and the Hereafter.

Therefore, it is integral to understand the true spirit of these guidelines which the Promised Messiahas wanted us to develop within us, that is, we should not simply perform these superficially, rather we should understand the true spirit and essence of these teachings. We must assess ourselves whilst being mindful of this, that is, are we attending this convention with this intention? Do we have the heartfelt passion to attain these objectives?

If, due to human weaknesses, we have erred in the past while striving towards these objectives, then are we ready now with a renewed sense of passion to endeavour towards this with the best of our capabilities to exhibit and establish these righteous deeds? Are we going to adopt this practice?

Today, do we pledge that we will become those who are more concerned about the life in the Hereafter than the life of this world? Do we pledge to give preference to the fear and love of God over everything else? Will we endeavour as much as possible to tread the subtle paths of righteousness and will we establish kindness in our hearts towards others? Will we increase our mutual love and brotherhood to the extent that it becomes an example for others to follow? Will we become those who progress in humility and politeness? Will honesty and virtue become our distinctive feature to the extent that everyone will say, “Ahmadis always remain firm on the truth and they speak the truth at any cost, even if they have to endure great losses in doing so”? Will we be ever ready to render exemplary services for our faith?

In order for this to be achieved, we must endeavour to propagate the message of God’s religion more than ever before to every individual in our society. We must inform them about the true image of Islam. If we can fulfil this pledge and we spend our lives accordingly, then we have indeed accomplished our pledge of allegiance.

Thus, let us establish our course of action to attain these goals. A person who is worried about the Hereafter and fears Allah Almighty, directs their attention towards safeguarding their worship. Such a person seeks to enquire the primary objective of their life which God Almighty has established for them. In relation to this, Allah Almighty states:

وَمَا خَلَقۡتُ الۡجِنَّ وَالۡاِنۡسَ اِلَّا لِیَعۡبُدُوۡنِ

The Promised Messiahas has translated this verse in the following manner:

“‘The Jinn and man have been created so that they may recognise Me and worship Me [Surah al-Dhariyat, Ch.51: V.57].’” He further states, “Hence, in light of this, the real objective of one’s life is to worship God Almighty and to become devoted to God and to attain the cognisance of God.”

The Promised Messiahas further states:

“It is obvious that a human being does not possess the status to decide the purpose of his or her life.” Although, a human being does try to decide that, however, they do not have the ability to do so. “Neither do they come to this world by their own choice, nor do they leave on their own accord. They are merely a creation. The One Who created them and granted them excellent and superior faculties when compared to other animals, He has established a purpose for their life, whether someone understands this or not. The purpose of the creation of humanity, without a doubt, is to worship God and to wholly devote oneself in seeking the cognisance of God and to immerse oneself in Him.” (Islami Usul Ki Philosophy, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 10, p. 414)

However, what is the method of this worship which God Almighty has taught us in order to attain this objective? It is to establish prayer. Allah the Almighty states:

اِنَّ الصَّلٰوۃَ کَانَتۡ عَلَی الۡمُؤۡمِنِیۡنَ کِتٰبًا مَّوۡقُوۡتًا

“Verily prayer is enjoined on the believers to be performed at fixed hours.” [Surah al-Nisa, Ch.4: V.104]

The Promised Messiahas states, “Offering prayers at the fixed hours is something that I hold very dear to me.” (Malfuzat, Vol. 3, p. 63)

This means that it is vital to offer prayers at its prescribed time. However, we see in this day and age that prayers are not offered on time due to very trivial reasons and people show negligence in this regard. In fact, there are some people who do not offer prayers altogether. They offer three or four prayers instead of the five daily prayers and show indolence in this regard, whereas Allah Almighty has commanded the believers to protect their prayers. He states:

حٰفِظُوۡا عَلَی الصَّلَوٰتِ وَالصَّلٰوۃِ الۡوُسۡطٰی

“Watch over Prayers and the middle Prayer.” [Surah al-Baqrah, Ch.2: V.239]

This means that we should watch over our prayers, particularly the middle prayer. However, due to worldly endeavours and employment, some people miss their Zuhr and Asr prayers and because of television programmes or other personal plans in the evening, they miss their Maghrib and Isha prayers. Some miss Fajr and use sleep as an excuse. Hence, every one of us must evaluate ourselves and see whether or not we are acting on the commandment of Allah Almighty.

There are some people who offer prayers in congregation during special Jamaat programmes or in the month of Ramadan and consider this as following the commandments of Allah Almighty, and it does not matter whether or not they adhere to these commandments during the rest of the year. However, one must pay heed to what Allah the Almighty and His Messengersa have said about the importance of observing prayer. Allah Almighty states:

اِنَّمَا یَعۡمُرُ مَسٰجِدَ اللّٰہِ مَنۡ اٰمَنَ بِاللّٰہِ وَ الۡیَوۡمِ الۡاٰخِرِ

“He alone can keep the Mosques of Allah in a good and flourishing condition who believes in Allah, and the Last Day [Surah al-Taubah, Ch.9: V.18] ”

The Holy Prophetsa stated, “When you see someone come to the mosque to offer prayers, then you should testify that such an individual is a believer. This is because Allah the Almighty states that only those individuals populate the mosque who believe in God and the Last Day.” (Sunan ibn Majah, Kitab-ul-Masajid Wa Al-Jamaat)

Although we all call ourselves believers, but only those people are believers in the sight of God and His Messengersa who populate His house, and this is because they believe in Allah the Almighty and the Last Day. Thus, it is also made clear here that simply coming to the mosque is not enough; rather, it is vital to attend the mosque with a firm belief in Allah and the Hereafter.

Whosoever adopts this mindset will fear God and such an individual will not come to the mosque to create disorder and will not be one of those worshippers whose prayers become a means of their ruin. Instead of attaining Allah’s pleasure, such worshippers incur the wrath of God. However, those who are truly righteous are concerned about the Hereafter and instil the fear of God in their hearts.

Their hearts are tender and filled with love, affection and brotherhood. They are humble and remain established on truthfulness. They propagate the peaceful message of Islam. Their mosques are places which one does not fear and nor are they places where evil ploys are hatched. It is for this reason that God Almighty states that only stand in those mosques whose foundations have been established on Taqwa [righteousness] and not to spread evil and disorder. Thus, those who populate the mosques while remaining firm on Taqwa, they also fulfil the due rights of God and also the rights of His creation. It is regarding these very people the Holy Prophetsa has given the glad-tiding that on the Day of Judgment, the first question that His servants will be asked about is the observance of prayer. God Almighty will ask the angels whether or not they offered their obligatory prayers; those who have offered all their prayers, their account in this regard will be complete and will declare that they have observed all their prayers. However, those who have some deficiencies in their obligatory prayers, God Almighty will ask about their nawafil prayers [voluntary prayers]; if there is any shortcoming in the observance of obligatory prayers, it can be fulfilled from their nawafil prayers. (Sunan Abi Daud, Kitab-ul-Salat, Hadith no. 864)

Thus, God Almighty stating “His servants” signifies that these people strive in the servitude of God Almighty and seek to fulfil His due rights. At times, in certain extreme cases and owing to one’s natural weaknesses, there can be shortcomings or one can forget, however God Almighty, granting His mercy and forgiveness, fulfils the deficiencies of one’s obligatory prayers by accepting their nawafil in its place and thus forgives His servant and increases his deeds in this way. However, those who offer the nawafil prayers are ones who instil the fear of God Almighty in their hearts. Nawafil is a prayer which one does not even have to leave their home to offer, rather it is offered in seclusion and in privacy, thus one who offers the nawafil prayers truly fears God Almighty. These are the very people regarding whom God Almighty states that they are “My servants”. Indeed, His servants can err, but they do not persistently go on committing them, in fact they seek to expiate those sins. Thus, this is the mercy of God Almighty whereby on the one hand, God Almighty has stated that prayer is not an ordinary matter and that is the very first thing which one will be asked, therefore one must pay attention to this, but on the other hand God Almighty has also stated that if one enters the servitude of God and fulfils the rights of His worship whilst adopting Taqwa [righteousness], then the nawafil will be of the same rank in virtue as the obligatory prayers and will cover His servants in the mantle of His forgiveness.

Therefore, on the one hand, whilst God Almighty has given glad tidings of His forgiveness, He has also directed our attention towards offering the nawafil prayers in order to become the recipient of His grace. Hence, a believer is one who whilst adopting the fear of God Almighty, not only directs his/her attention towards observing the obligatory prayers, but also observes the nawafil, so that they can fulfil any shortcomings in the obligatory prayers. These are the people who truly fear Allah the Almighty and adopt Taqwa – and it is owing to Taqwa that their attention is then directed towards fulfilling other virtuous deeds as well. Their hearts become tender for one another and instead of seeking revenge, they forgive one another.

In order to attain the love of God Almighty, they treat one another with love and affection and their hearts are filled with humility. They develop a spirit of sacrificing for the sake of others. Therefore, in this regard, everyone should assess their own condition as to whether they have these characteristics. A true believer is one who strives to adopt every form of virtue. If a person does not show love towards his fellow brother, then he does not have true Taqwa within him. Similarly, one should be concerned if they are not kind-hearted. One whose wife and children are deeply annoyed at him over his conduct, lacks in Taqwa. Similarly, those wives who fail to fulfil the rights of their husbands and children and make unjust demands, their hearts are also devoid of Taqwa. Those who treat one another with love and kindness for the sake of God Almighty, they are the ones who truly adopt Taqwa. The Holy Prophetsa stated that on the Day of Judgment, God Almighty will declare:

“Where are those who love each other for the sake of My glory? Today, I will shelter them in My shade on a day when there is no shade but Mine.” (Sahih Muslim, Kitab-ul-Birr, Hadith no. 2566)

Thus, those who love one another whilst adhering to the commandments of God Almighty purely for His sake, they are the ones who become the recipients of His grace. On the other hand, those who do not do this can incur the displeasure of God Almighty. Therefore, each and every one of you must instil this spirit within them. We proclaim the slogan of “Love for all, hatred for none”, however we must practise this within our own homes and in our societies so that this message can spread in the world in the true sense. Moreover, through just a small effort on our part, we can enter the shade of God Almighty’s mercy. On numerous occasions, the Holy Prophetsa has granted advice on how one can establish peace and tranquillity in society and to increase love, affection and brotherhood for one another. In regard to this, the Holy Prophetsa once stated:

“Muslims are brothers of one another, he does not treat his brother unjustly and nor abandons him.”

The Holy Prophetsa also stated:

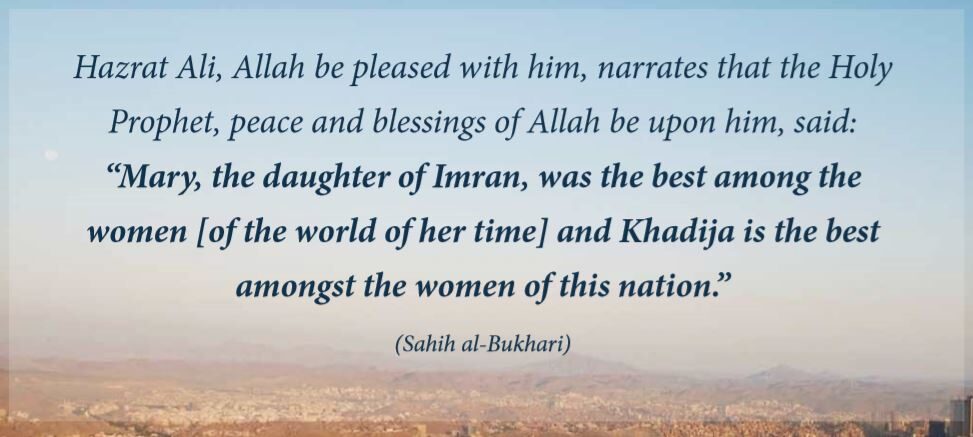

“One who remains occupied in helping his fellow brother, God Almighty Himself fulfils his needs. Whosoever alleviates his brother’s affliction, God Almighty shall lessen one affliction from him on the Day of Judgment. One who covers the fault of his fellow brother, God Almighty shall also cover his fault on the Day of Judgment.” (Sahih Al-Bukhari, Kitab-ul-Mazalim, Hadith no. 2442)

Thus, God Almighty bestows His mercy and benevolence through different means and provides means of our forgiveness, but despite this if one incurs the displeasure of God Almighty, then it is owing to his own inefficiencies, ego and stubbornness incurs the displeasure of God Almighty.

Thus, one should be greatly concerned and deeply ponder over this matter. During these days while everyone’s attention and emotions are directed towards virtue and you have also gathered here with the view that you are to take part in a gathering where you will listen to talks of virtue and piety, you should asses your conditions and focus towards fulfilling the rights of God Almighty and His creation. You should seek to recognise the true essence of developing kindness and love for one another and also humility.

This is also important for us to achieve because the pledge of Bai‘at that we have taken with the Promised Messiahas is on the conditions of abstaining from Shirk, observing prayers – both obligatory and voluntary prayers – but also in addition to these conditions is that under the impulse of any passions, he/she shall cause no harm whatsoever to the creatures of God in general and Muslims in particular.

This is not only limited towards fellow Muslims or members of the Jamaat; indeed we must begin from our own home, then in our dealings with other Muslims, but then ultimately, this should apply to the whole of mankind and we should have love and affection in our hearts for every single person. We must become free from our inner passions and we should also treat our subordinates with kindness. Our conduct should be such that if anyone wishes to assess and determine whether our standard is according to what we claim, they may do so. Moreover, when others assess our standard and it is truly according to what we claim, only then can we say that indeed we are true believers and are fulfilling the due rights of our Bai‘at.

Another condition of our Bai‘at is that he/she shall entirely give up pride and vanity and adopt humility and meekness. (Izala Auham, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 3, p. 564)

To adopt humility and meekness is not just one of the objectives for which the Promised Messiahas established the Jalsa [annual convention], in fact to adopt meekness and humility is also amongst the conditions of the Bai‘at that we have pledged with the Promised Messiahas. Thus, it is our responsibility to fulfil this pledge and this in fact is the very first step towards the truthfulness that is to fulfil the pledge we have made. Therefore, we should regularly read the conditions of our Bai‘at and assess whether we are holding true to these conditions and striving to lead our lives according to them. If this is not the case, then our claim of wanting to reform the world is wrong, therefore we should first seek to reform ourselves, otherwise we would be counted amongst those whose actions are not in harmony with their words and God Almighty has expressed His displeasure at such people. Moreover, in such an instance, instead of testifying to the truth, our actions would be testifying to falsehood. When there is incongruity between our words and deeds, then our claim to serve faith and all our efforts towards this will also be false. Indeed, the Promised Messiahas is true, his claims are true, there is no doubt that God Almighty has vouchsafed His promises of granting him victory; indeed, God Almighty has promised to grant him a Jamaat of sincere devotees, but if our condition remains the same, then we will not be counted amongst those who are the true helpers of the Promised Messiah’sas Jamaat.

Therefore, in order to receive the blessings of our Bai‘at, we must assess our conditions and also ponder over the objectives of the Jalsa. We are very fortunate that we have been granted three days of the Jalsa to reflect over this. Thus, each and every one of you should assess their condition and instead of engaging in idle conversations, you should spend your time in supplications, seeking forgiveness and sending salutations upon the Holy Prophetsa [Durood], it is only then that we can truly benefit from the Jalsa. The Promised Messiahas states:

“The members of my Jamaat, wherever they might be, should listen with attention. The purpose of their joining this Movement and establishing the mutual relationship of spiritual preceptor and disciple with me is that they should achieve a high degree of good conduct, good behaviour and righteousness. No wrongdoing, mischief or misconduct should even approach them.”

This is the standard of true Taqwa, in that they should be free of such ills. The Promised Messiahas states:

“They should perform the five daily prayers regularly in congregation, should not utter falsehood and should not hurt anyone by their tongues. They should be guilty of no vice and should not let even a thought of any mischief, wrong, disorderliness or turmoil pass through their minds. They should shun every type of sin, offence, undesirable action, passion and unmannerly behaviour. They should become pure-hearted and meek servants of God Almighty (they should become such individuals whose hearts are pure and free from all ills). And no poisonous germ should flourish in their beings.

“Sympathy with mankind should be their principle and they should fear God Almighty. They should safeguard their tongues and their hands and their thoughts against every kind of impurity, disorderliness and dishonesty. They should observe the five daily prayer services without fail. They should refrain from every kind of wrong, transgression, dishonesty, bribery, trespass, and partiality.”

One should refrain from usurping the rights of others, showing unlawful bias and causing harm to others.

The Promised Messiahas further states:

“They should not participate in any evil company.”

The youth should be mindful of ensuring to abstain from keeping bad company and the parents should also be mindful of this and ensure that their children are not keeping bad company, otherwise they will take their influence and become like them. The Promised Messiahas further states:

“If it should be proved that one who frequents the company of such a one who does not obey God’s commandments … or is not mindful of the rights of people, or is cruel or mischievous, or is ill-behaved then it should be their duty to repel him and to keep away from such a dangerous one.” Thus, an Ahmadi should always keep good company.

The Promised Messiahas further states:

“They should not design harm against the followers of any religion or the members of any tribe or group. Be true well-wishers of everyone.”

If one wishes to advise others, they should do so in a sincere manner, in other words, one’s speech and actions should be such that the words of advice should have an impact and one should not show bias towards anyone. The Promised Messiahas states:

“And take care that no mischievous or vicious person, or disorderly one or ill-behaved one should ever be of your company or should dwell among you for such a person could, at any time, be the cause of your stumbling.”

The Promised Messiahas states:

“It is the duty of every member of my Jamaat to act upon these instructions. You should indulge in no impurity, mockery or derision. Walk upon the earth with good hearts, pure tempers, and pure thoughts. Do not attack anyone improperly and keep your passions under complete control. If you take part in a discussion or in an exchange of views on a religious subject, express yourself gently and be courteous. If anyone misbehaves towards you, withdraw from such company with a greeting of peace.

God Almighty desires that you should become a Jamaat that should set an example of goodness and truthfulness for the whole world. Therefore, be alert, and be truly good-hearted, gentle and righteous. You will be known by your regular attendance at prayer services and your high moral qualities.”

Thus, you will be recognised by your observance of the five daily prayers and high morals. If you can develop these traits, then consider that you have fulfilled the rights of your Bai‘at.

The Promised Messiahas further states:

“He who has the seed of evil embedded in him will not be able to conform to this admonition.” (Majmua Ishtiharat, Vol. 3, pp. 46-48, Ishtihar no. 188)

May God Almighty grant us all the ability to fulfil the rights of our Bai‘at with the Promised Messiahas and may we adhere to his instructions and fulfil his expectation from us.

May we also avail as much benefit as possible from this Jalsa and thereby improve our religious, spiritual and intellectual conditions, and then may we continue to remain established upon these virtuous deeds.

(Original Urdu published in Al Fazl International, 25 October 2019, pp. 5-8. Translated by The Review of Religions.)