Naosheyrvaan Nasir, Student at The University of Sydney

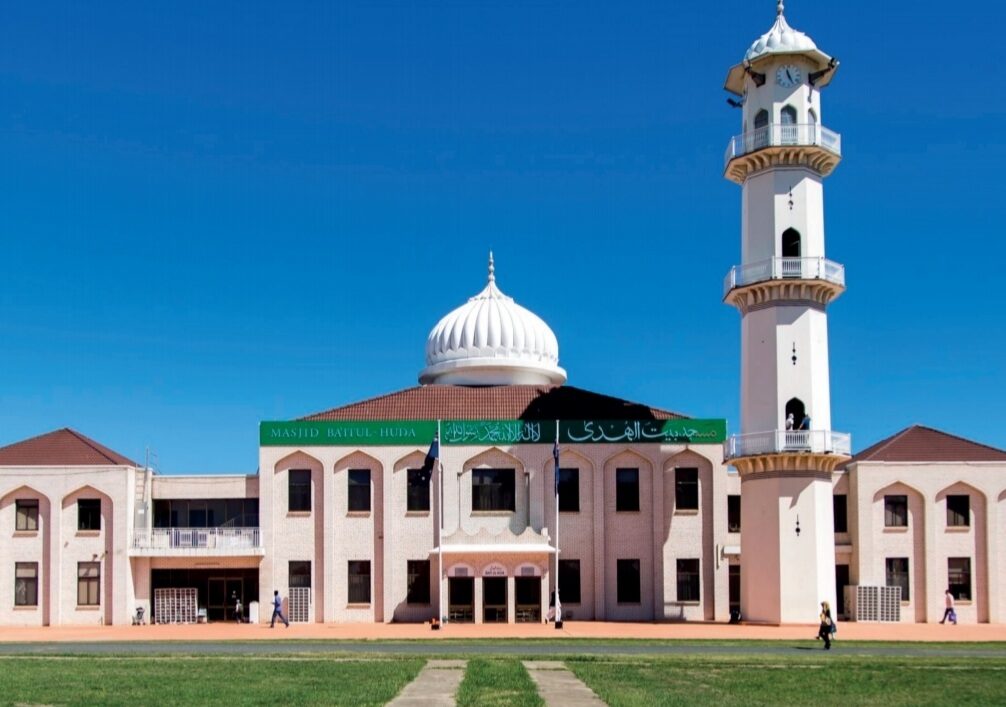

Being born and bred in a country like Australia where religious freedom is guaranteed, going to the mosque is the norm for me. However, the recent – and historically unprecedented – closure of the Bait-ul-Huda Mosque in Sydney due to the Omicron variant’s hold over the state of New South Wales shook me to the core.

Pre-Covid, travelling to the mosque was part of my weekly routine. During the weekdays I would go to school and on Sundays, I would aim to reach the mosque by 10 am for either Sunday school, Waqar-e-Amal (manual labour), or to attend a programme or event which was followed by prayers.

Ever since the mosque was closed in late December of 2021 (literally just two days out from Jalsa Salana) there has been a mosque-shaped hole in my heart whose sting is most painful. My social circle, the skills I gained in administration and teamwork and the people whom I sought career advice from all stemmed from my commitment to go to the mosque. It was my happy place, a place I took pride in talking about when my peers at school would ask me on Monday “how was your weekend?”. I would only mention what I got up to at the mosque as that was always the highlight of my weekend.

This pang that I feel reminds me of a verse from the Holy Quran. In chapter 13 verse 29 it says that “Those who believe, and whose hearts find comfort in the remembrance of Allah. Aye! It is in the remembrance of Allah that hearts can find comfort”. It is only now when the mosque has been closed for an extended period that I have come to truly understand the value it has in my life. It is through my commitment to keeping the mosque relevant to the modern age that my heart finds comfort. Both spiritual comfort through the sense of purpose it gives and worldly comfort through the social and professional networks it opens and the attainment of new skills.

Before the current Omicron outbreak, the mosque did close briefly yet there was some leeway for activities to continue albeit at a reduced scale. During those days I was able to come to the mosque sometimes, but it is not like the condition now where it is simply a concrete decision that the mosque is closed and there is no getting around that blanket ban.

Interestingly, this pang can also be explained using behavioural psychology and behavioural economics through the concept of loss aversion. The theory goes that if an individual is endowed with a product, then the individual will take all the steps necessary to stop that product from being taken away as the loss of losing that product has a much greater effect than the pleasure of gaining it in the first place. To put it another way, “the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining” (www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/loss-aversion/)

In my case, as an Ahmadi Muslim in Sydney, I have been endowed the pleasure of going to the mosque every week for as long as I can remember. However, when that pleasure was taken away from me the pain of not going to the mosque felt at least twice as much as the gain I got from when I did go to the mosque. Of course, reasoning out why the pain is twice as much as the gain is a rabbit hole in itself, but the principle is clear; I miss going to the mosque nowadays.