Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

Studies in Islamic history can be riddled with multiple reports from multiple sources muddling up the details of a certain event and, more so, a series of events. With geographical descriptions, this challenge is even more enhanced, thanks to the names of places and locations having changed not once but multiple times over the course of many centuries.

Trying to track the journey of the Holy Prophetsa for the Conquest of Mecca has put the author through the same challenge. Why this attempt was even undertaken is down to the presence of one location in the Holy Prophet’ssa entire journey during this historic conquest, and that too at the very end when he made his final descent into Mecca – a mountain called Jabal Hindi.

While the motive can simply be put down as the author belonging to the Indian Subcontinent, which was broadly named al-Hind in the time of the Holy Prophetsa, the details that emerged during this personal vocation can be of interest for researchers in the geographical imagination of early Islam, and its tributaries that run into Islamic eschatology.

Al-Hind in pre-Islamic Arabia

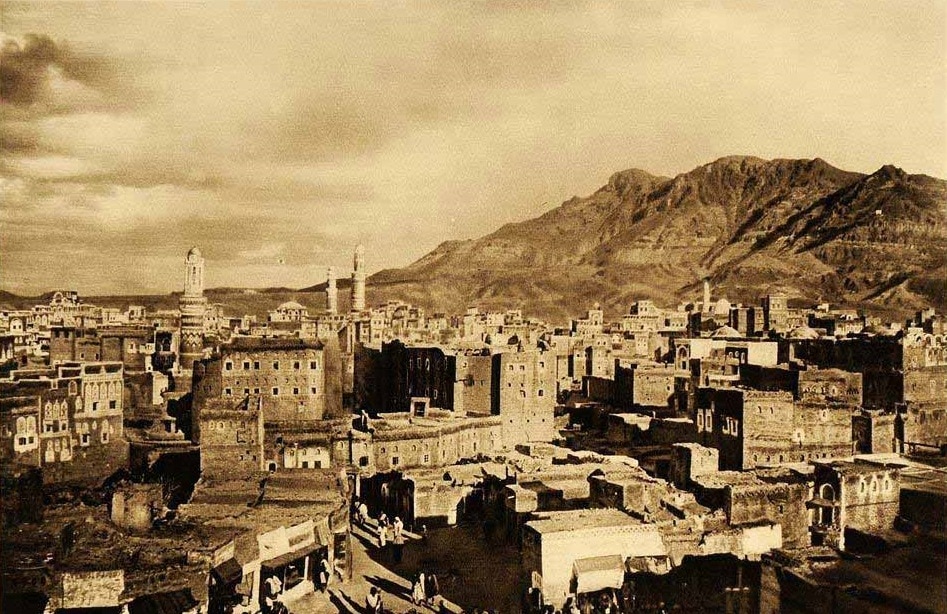

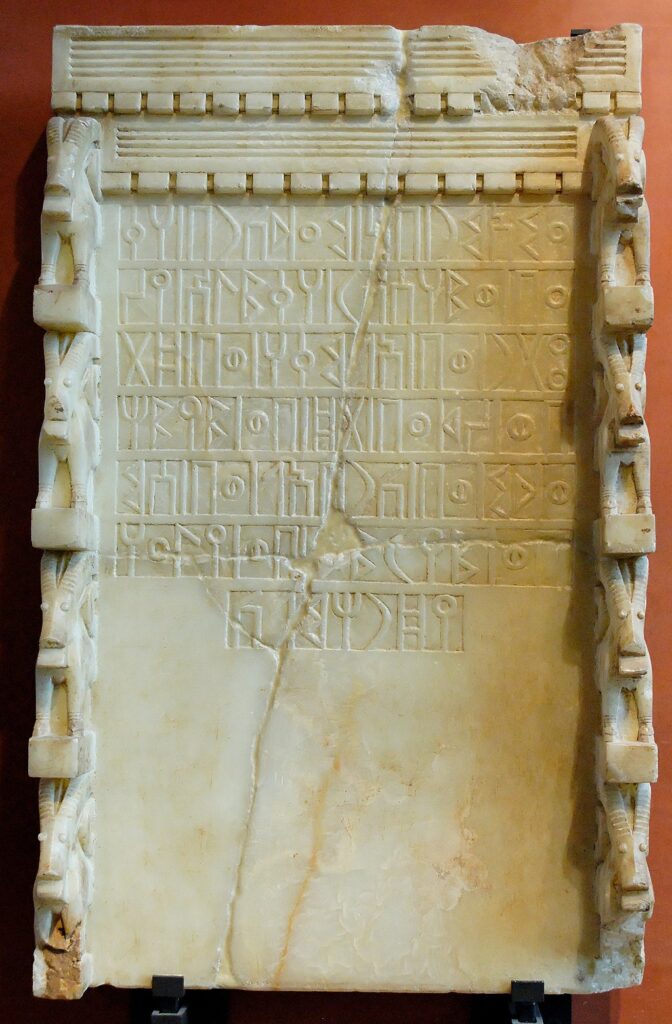

In the 1930s, some rock inscriptions were discovered near Jabal al-‘Uqla in the Sanaa region of Yemen, dating back to around 270-280 CE. Written in Sabaic language, the texts refer to a royal ceremony apparently held in honour of a Hadramite king.

The texts mention the presence of Qrshtn, deciphered by Albert Jamme to mean Qurayshite women, along with representatives of Tadmar, Kashd, and Hind.1 While the objectives of this meeting in Hadramawt remain unclear, it is generally assumed that the meeting must have been about matters of trade.

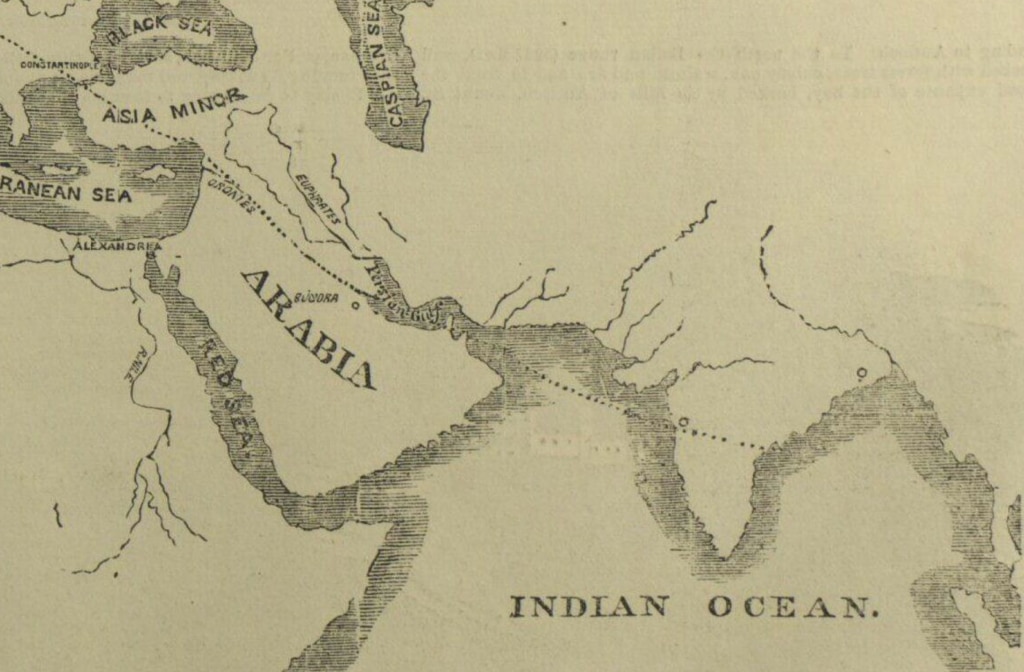

Despite Patricia Crone’s sceptical views, it is a well-established fact that there were, from prehistoric times, strong trade links between Hind and Arabia – or the Indus Valley and the Mesopotamian Civilisations to start with.2 However, we will limit this piece to focus only on late antiquity – 250 to 750 CE3 – and hence keep this study restricted to the eve of Islam and its advent.

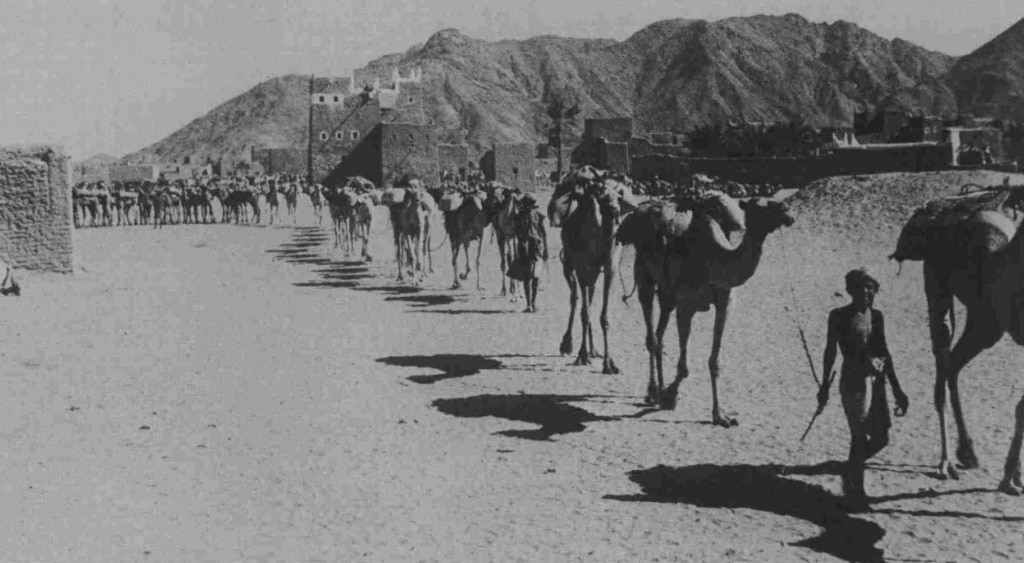

This trade route, commonly known as the Levant trade route, had developed and evolved over centuries, having flown east to west, both on land and through the sea. Ibn Khurdadbeh, the 9th-century Persian geographer, lists the products traded from India to the Arab lands:

Oud, sandalwood, camphor, clove, nutmeg, tamarind, pepper, cotton, bamboo sticks (for spears and arrows), and, most importantly, the Indian sword known in the Arab world as Saif Hindi (also called muhannad and hindwani).4

The Incense Route

The greatest consumer market for the above was around the Mediterranean basin, more so in Syria, where Byzantine traders purchased the goods to take them further into European lands. In the absence of a direct route for Indian merchants to reach the Mediterranean basin, they had to have intermediaries, and they found them in Southern Arabia (now Yemen and Oman) and along the western coast of the Arabian/Persian Gulf.

The western coast of India is linked by sea to the eastern coast of Arabia through a straight line. However, history has it that Indian ships would stick close to the coastal land all along to avoid the dangers posed by rough seas. In doing so, they would safely land on the coast of Oman.

Travelling further on, along the coast of modern-day Yemen, through the ports of Aden and Hadarmawt, they would be met by Arab merchants who would buy the Indian produce/products. It was from here that the Arabs, through the Arabian mainland trade route, would transport the merchandise to Syrian commercial centres. The most feasible, hence popular, trade route remained the route through the Hijaz – along Arabia’s west coast and the Siwar mountain range. The presence of oases and vegetation along the route earned it popularity. Along this route were situated the towns of Mecca and Medina – both to later become centres of Islam.

Indian merchants arriving by sea would not always travel straight on, but navigate northwards into the Arabian/Persian Gulf, stopping briefly at various ports before reaching the final destination of Uballah (modern-day Basra) – also known in the early days of Islam as “the marches of India”.5 Having traded all along this route at the various ports, they would finally trade their merchandise to the Byzantine conduits in Syria. This was along the east coast of Arabia.

Between the eastern and western coasts, the Arabian Peninsula was an epitome of barren land and harsh climatic conditions. The traders from al-Hind were neither accustomed to such harsh weather nor did the monopoly of the Arab intermediaries allow them any further advance.

It was this centuries-old trade route of Indian frankincense and spices, from southern Arabia to Syria, via the Hijaz, that earned it the name of the Incense Route.

Settlers of Indian origin in pre-Islamic Arabia

Centuries of interaction between Arabs and Indians through trade led to more ways for the two nations to mingle. Between the two fell the vast Sassanid Empire with its sophisticated control over land and sea trade routes.

Moreover, the expanse of the empire on each side, east and west, bordered with al-Hind and Arabia, respectively. The borders to the east met the Indian Subcontinent at what we today know as Sind and Baluchistan. This, for the mediaeval Arab, was al-Sind.

Ibn Manzur, in Lisan al-Arab, describes the Zutt as an Arabicised name for those known as “Jatt in the Indian language” and are “dark-skinned” and of “Indian origin”.6 Other social historians have given the same/similar descriptions,7 while Abul Fida, in Taqwim al-Buldan, brackets the Baluch as Zutt.8

They were clearly known as people originating from al-Sind and al-Hind and spread across both expanses of lands – from Makran to Mansura,9 from Sind to Multan.10

While the two could be interchangeably used, some Arab geographers from later mediaeval times identified al-Sind as the gateway into al-Hind – the latter being the vast land that lay beyond the former, all the way up to al-Sin, or what we know as China.

Interaction with the people of al-Hind had attracted them into the Sassanid lands in various roles. Some were recruited into the military, famously known as the Elephant Corps. Hired from India, the Elephant Corps of the Sassanid army held a very prominent position by being foremost in the four major ranks; the elephants, the horses, the archers, and the ordinary footmen, respectively.11

As the elephants and their riders came from India, the chief of the Elephant Corps was known as Zend-kapet, meaning commander of the Indians.12

The Arabian/Persian Gulf had Arabian land as its western shore, while the east was entirely the Sassanid coast, guarded by Sassanid armies of which the Indians were an important part. Where Indian traders had inhabited the east coast of the Arabian Gulf, Indian soldiers, as part of the Sassanid army, had settlements on the west.

Major conflicts between the Sassanid and South Arabian rulers, and the dominance and control of the former over South Arabian lands, led to Indian troops settling in the south of the Arabian peninsula – the fountainhead of the Arab-Syrian trade.

These Sassanid troops were Zutt, which is the Arabicised form of Jatt (also spelt Jaat) – a well-known Indian caste. Known to have come from the South of the Indus Valley civilisation, they were also known as Rejal al-Sind or the people of Sind. As discussed above, al-Sind and al-Hind were interchangeably used in the pre- and early-Islamic Arabia.

Other peoples from al-Sind and al-Hind are known to have inhabited Mediaeval Arabia, but from many centuries before. The Med were a people from the Baluchistan coastal region of Makran. They were known to the early Arabs, through sea trade, as pirates of the Indian seacoast.13

However, some factions of the Meds had travelled across the sea and settled along the Arabian coasts. Other peoples, like the Bayasira, Ahamira (Himyarites) and the Siyabija, were also of Indian origin who, like the Zutts and the Meds, gradually settled along the Arabian coasts, especially towards the south (modern-day Oman and Yemen), and assimilated into the Arab lands and their respective indigenous societies.

Baladhuri, in Futuh al-Baldan, describes the Siyabija as having inhabited “the coastal lands of the Arabian Gulf before Islam”.14 He goes on to state that “same is the case with the Zutt […]”15

Jahiz, in his book Kitab al-Hayawan, quotes a pre-Islamic poet who used the Zutt song as a simile for the whining of a mosquito – proof that people of Indian origin were so much a part of the pre-Islamic society that such similes could make certain concepts easier to comprehend.

Having seen how well-integrated immigrants from al-Hind were in the pre-Islamic Arabian society, and primarily through trade, it will be helpful to see what goods they traded in and around Arabia.

Swords, spices and scents

Although known more commonly as the incense route, an eponym derived from Indian scents and spices, the south-north trade route through mainland Arabia was better known for trading Indian swords.

Briefly touched upon above, incenses like musk, oud, camphor and myrrh all were exported from their habitats in India to Arabia. That these incenses were commodities for the pre-Islamic Arabs is confirmed from, alongside other sources, the poetry of the jahiliyyah. Imr’ul Qais, praising the temptation of two women, wrote:

اذا قامتا تصنوع المسک منھما

نسیم الصبا جاءت بریا القرنفل

“When they both stand, from them emanates the fragrance of musk; as the morning breeze laden with the fragrance of clove”.

Nabigha al-Ja’di, a poet from jahiliyyah days but later converted to Islam, wrote:

أُلْقِيَ فِيهَا فِلْجَانِ مِنْ مِسْكِ دَا

رِينَ ، وَفِلْجٌ مِنْ فُلْفُلٍ ضَرِمِ

Saif Hindi, muhannad and qala’i, as the Indian swords were known, were accepted to be the best weapons for the war-obsessed natives of Arabia.

The pre-Islamic poet Zuhayr ibn abi Sulma said of the Saif Hindi:

کالھند وانی لا یخزیک مشھدہ

وسط السیوف اذا ما تضرب البھم

“The Hindi sword will not let you down; even if fighting an armed battalion.”

Tarafa ibn al-Abd, one of the seven poets celebrated through their mu’allaqat (the pre-Islamic hanging poetry at the Kaaba), praised the muhannad for its thrusting cut in his mu‘allaqah:

وظلم ذوی القربیٰ اشد مضاضۃً

علی المرٔ من وقع الحسام المھند

“A wound inflicted by someone close to us is way deeper and hurtful than one sustained through muhannad [Indian sword].”

Muhammad al-Idrisi, the renowned geographer, wrote about the Hindi swords in his work Nuzhat al-Mushtaq. The iron ore, wrote al-Idrisi, mined in Sifala and Zanj in the south of Hind, is taken to bladesmith foundries in other parts of al-Hind. He writes how Hindiyin (plural for Indian) were well versed in mixing chemicals (most probably oxidising and reducing agents), and then smelt the iron ore. The end product is then termed Indian iron, to turn it into swords and other forms of arms and armour. The best swords are manufactured in Hind, and, he states quite emphatically: “There is no sharper and better-slashing iron than that of India, and there is no doubt about it.”16

This emphasis on the quality and historicity of Indian iron and steel is justified by the fact that Alexander the Great, about 400 years BCE, brought back Indian steel, having used swords forged out of it.

Other arms and armour known for being of Indian origin, and extensively used in pre-Islamic Arabia, were spears and arrows made with bamboo sticks imported from Sind, Gujrat and Bharuch areas of west India.

Thus, India and people of Indian origin were an important faction of pre-Islamic society, best known for the defence weapons that they manufactured and supplied throughout the Arabian Peninsula, and beyond.

Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia

The existence of Jewish and Christian communities in pre-Islamic Arabia is an established fact and historians have extensively looked into their origins, settlements and integration into Arabian society.

But more than both, the presence of Paganism is even more emphasised when it comes to the emergence of Islam in both Islamic and Western histories of Arabia. The Holy Quran repeatedly mentions all three – the former two as Ahl al-Kitab (People of the Book), and the latter as idolaters and polytheists.

Despite this heavy presence of Pagans in the pre- and early-Islamic Arabia, Paganism remains a loose, blanket term to cover a variety of polytheist belief systems.

Since this part of our study focuses on the presence of Indians on and around the eve of Islam, it is this most mentioned and least studied category that we turn our attention to.

Paganism is often used to indicate religious practices and beliefs with no meaningful mutual connection, yet made to appear as one big community, especially when it comes to the opposition and persecution of nascent Islam.

We find mention of certain Pagans who worshipped a certain god, yet they are also seen as polytheists who, as the term suggests, worshipped more than one or a variety of gods. Whatever the case may have been, little attention is given to what the belief in any such god, or set of gods, entailed. One is bound to imagine that these groups must have had a strong set of beliefs, the strength of which is reflected in the intensity of the opposition to Islam.

If it were only a case of worshipping a certain god, as is conveniently portrayed by most, especially Muslim historians, then what kept them so firmly attached to their own god(s). To justify this strong affiliation, tribal bonds that ensured economic sustenance are brought into the picture, thus once again putting aside their faith and beliefs as unimportant.

With the ancient stone inscriptions found in southern, northern and coastal parts of Arabia, we are left with no choice but to believe that pagan beliefs were of significant faith value for their adherents.

Pagan stone inscriptions, deciphered painstakingly by Western archaeologists and historians, speak of animal sacrifice to gods, seeking their refuge, beseeching them for rain and blessings, etc. They are found praying for the well-being of the deceased, who, to their belief, are now with the gods that they beseech.

Since next to no archaeological evidence of pre-Islamic times (or even early-Islamic times) is available from the mainland Arabian Peninsula – the birthplace of Islam – one can only rely on the evidence available on the fringes of it. This evidence , especially of beseeching idols for the well-being of the deceased dear ones, strongly suggests that, in their eyes, idols carried a metaphysical status and not merely a physical one.

This means that the idols/gods placed in and around the Kaaba belonged to more than one religious group, and each one of them had a belief system attached.

It remains an uncontested fact that Paganism, in its loose and prevalent sense, had existed before the monotheist religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Clues in the Sabean riddle

Another less-mentioned existence in pre-Islamic Arabia is of a people called Sabeans (alt. Sabians, Sabaians). The Quran mentions them (al-Sabein, al-Sabiun) on three occasions and classes them among the Ahl al-Kitab or the People of the Book.17 Of the three occurrences, the first places them after Muslims (alla-zina Aamanu), Jews (alla-zina Haadu) and Christians (al-Nasara); the second places them between Jews and Christians, and the last places them between the two major faiths, but also adds another group named the Magians (al-Majus) and lastly the polytheists who associate other gods with Allah (alla-zina Ashraku).

To surmise, we can say that the Holy Quran identifies five major religious belief systems that preceded Islam: Jews, Christians, Sabeans, Magians and those who associated other gods with God.18 This clearly suggests that the last group (Mushrikun) too believed in God but associated other gods with the Supreme God – the God of Abrahamas.

That the Holy Quran mentions Sabeans alongside major world religions of its time leaves no reason for the Sabeans to be brushed away as a negligible religious community. The Holy Quran acknowledges the diversity of religions by stating, “wa li kulli qaumin haad”.19 When mentioning major Prophets and messengers, the Holy Quran chooses, as a set, Noahas, Abrahamas, Mosesas, Jesusas and the Holy Prophetsa of Islam:

شَرَعَ لَكُم مِّنَ الدِّينِ مَا وَصَّىٰ بِهِ نُوحًا وَالَّذِي أَوْحَيْنَا إِلَيْكَ وَمَا وَصَّيْنَا بِهِ إِبْرَاهِيمَ وَمُوسَىٰ وَعِيسَىٰ ۖ أَنْ أَقِيمُوا الدِّينَ وَلَا تَتَفَرَّقُوا فِيهِ

“He [Allah] has ordained for you the way which He decreed for Noah, and what We [Allah] have revealed to you, and what We decreed for Abrahamas, Mosesas and Jesusas; commanding: ‘Uphold the faith, and make no divisions in it […]”20

Now here we have two sets: a set of major faiths, and another of major Prophets, namely Noahas, Abrahamas, Mosesas and Jesusas. It is hence quite logical to think that the ahl al-kitab mentioned in the aforementioned verses of the Holy Quran – the Muminun, the Yahud, the Nasara and the Sabe’in – have to have origins in the religions founded by the four champion Prophets.

Having remained a contestant religious group with, in reverse order, the Muslims, Christians, and Jews, the Sabeans predate all three, and have to have origins in Abrahamic teachings or that of Noah for that matter.

Since the Holy Quran does not provide any details about the Sabeans, commentators of the Holy Quran have only relied on conjecture and have thus only been able to formulate opinions. However, historical evidence suggests, and most commentators of the Holy Quran seem to agree, that the origin of the Sabeans could be traced back to Iraq – the historical region of Mesopotamia, and the birthplace of Abrahamas.

Historical and archaeological evidence also leaves no room to deny the economic, and the subsequent social intercourse, of the Mesopotamian and the Indus Valley civilisations. Historians have been able to see how deeply Mesopotamian religious beliefs affected Indic belief systems in the Indus Valley. Indologists like Stephan H Levitt have concluded that “Indic religion is in large part a religion of Ancient Mesopotamian type […]” 21

This export of the Mesopotamian belief system is said to have taken place in the last two millennia BCE, the latter part of which was termed the Axial Age by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers – when the pre-Islamic religious theatre was being set for Islam.22

This was an era when prominent religious figures appeared and when previous religious texts were being compiled – the works of Lao-Tzu, Buddha, Greek philosophers, Hebrew Prophets and the Hindu Upanishads.[23]

This Abrahamic faith, albeit in its altered form, underwent further distortion to take a completely new shape of the Vedic tributaries of Hinduism. Gravitated towards their spiritual source, or that of Abrahamas, the Barahmans from this morphed faith are said to have travelled to Mecca to worship their idols in the vicinity of the shrine of the Kaaba. 23

Why the Abrahamic faith so easily gave way to idol worship could have multiple reasons. One of many could be the fact that Abraham’sas faith had sprung up in Mesopotamia at a time when idol worship was part of the common belief systems of his time. He was born, as the Holy Quran attests, not only to an idol-worshipping family, but also one that sculpted them as a means of living. His initial revolt, which marks his proclamation of his newfound monotheistic faith, was against this idol-making, idol-worshipping family and community. 24

Thus, his faith, the genesis of which had been in the midst of idol worship, seems to have reached the Indus Valley along with idols having made their way into it. In addition, the Indus Valley, or al-Hind, which was already imbued in idol worship from ancient times, welcomed it with open arms – only that they now had a Supreme God, or Abraham’sas God, at the centre of their polytheistic practices. Indo-Islamic enthusiasts have drawn parallels between Brahma of the Hindu faith, and Abrahamas, being deeper than merely being an apparent namesake.

Such studies point to Brahma in the Rigveda being “father of all”25, while Biblical Abraham is “father of many nations.”26 Brahma’s wife is Sarasvati and of extraordinary beauty,27 and so is Abraham’s wife, Sara.28 Similarly, the Vedic couple has their first son at the age of a hundred, and so do Abrahamas and his wife.29 More strikingly, Brahma’s son (or grandson) is offered as a sacrifice, but is resurrected with the head of a ram;30 Abraham’sas son is almost slaughtered as a sacrifice but is rescued by a ram, which is killed in lieu of his son.31

With these stark indicators in favour of Vedic origins in the Abrahamic faith, it intrigued the earliest of Indo-Islamic scholars, like al-Biruni, to understand how idol worship seeped through a strictly monotheistic faith.

Idol-worship in religions of al-Hind

Al-Biruni, in his Tahqiq ma lil Hind maintains that the uneducated commoners, or al-aami/al-awaam as he calls them, had been accustomed to worshipping concrete (mahsus) objects for many centuries and, hence, required physical, tangible symbols to aid their worship of the abstract (ma‘qul) Supreme God that they were being introduced to. The educated class, and those with a deeper understanding, worshipped, and still worship, the One God.32

While al-Biruni’s study was a sociological and not a polemic one, Abu Fath al-Shahrastani (d. 1153) delved into the theological understanding of Hindu idol worship. In his magnum opus, Kitab al-milal wa al-nihal, al-Shahrastani traces the Sabean origins of the Hindu faith, acknowledging the prophetic status of Visnu and Siva – two spiritual figures (ruhaniyat) sent to the people of al-Hind.33

Between al-Biruni and al-Shahrastani falls another prominent scholar, al-Gardizi (d. 1061), who traced monotheistic traits in Hindu Brahmans (al-muwahhida al-barahima) through, as they believed, “an angel sent to them in human form,” i.e., a Prophet.34

These unique insights, from the 11th and 12th-century scholars, into Hinduism’s monotheistic origins were not too keenly welcomed by Muslim scholars for a long span of centuries. However, prominent mystic (sufi), Muslim figures kept the intrigue alive.

Chishti sufi Amir Khusraw (d. 1325), in his famous poetical work Nur Sipihr, described them as

معترفِ وحدت و ہستی و قدام

قدرتِ ایجادِ ہمہ بعدِ عدام

“Believers in unity and existence since eternity, into eternity after the doomsday”

Moving towards more modern times, a great Mughal figure, Dara Shukoh (d. 1659), a staunch adherent of the Qadiri order, and the son of emperor Shahjehan, spent a great part of his life investigating the monotheistic origins of Hinduism. His translations of the Upanishads into the Persian language are clear proof of his obsession with uncovering these hidden tracks. He sees Vedas as heavenly books, and that all heavenly books constitute commentary to each other.35

Taking this legacy forward, another Mughal figure and a Naqshbandi sufi, Mirza Mazhar Jan-i-Janan (d. 1781), also strove to prove the divine origin of the Vedas, revealed to the angel/Prophet Brahma. He went on to debate that all Hindu sects, in their original form, believed in One God. Idol worship does not violate their original monotheist belief but is rather a physical representation of God’s attributes.36

Jan-i-Janan understands the status of Krishna and Ram, referred to as Avtars in Hinduism, translatable in Muslim tradition as a saint of the highest order, i.e., Prophet or Messenger.37

In more recent times, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian, Founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, quite categorically gave Krishna the status of a Prophet of God. “The Holy Quran has it that و ان من امۃ الا خلا فیھا نذیر. And Hazrat Krishn was one of such messengers that God Almighty appointed for guiding the creation of Allah and to uphold the Oneness of Allah the Almighty […]”38

That Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’sas claims were met with bitter opposition, as if no Muslim scholar had ever seen Krishna as a Prophet, could be down to the two-tiered nature of his understanding about Krishna. Unlike his predecessors in this realm of enquiry, he did not merely hold his Krishna-notion as opinion but sealed it with divine assent by basing it on revelation. He took it even further and ascribed to himself as the second manifestation of Krishna. Kenneth Cragg notes:

“Ahmad’s claims were linked with the thought of the Mahdi or guide. Later still, he associated his vocation with the ideas of messiahship and with the name of Krishna. This eclecticism may have been an inverted form of concern about the multiplicity of religions […]”39

Hazrat Ahmadas, alongside the revealed status of his Krishna-notion, relied on a tradition of the Holy Prophetsa where he speaks of a Prophet in al-Hind, dark-skinned and named Kahen – the Arabicised version of Krishna’s sobriquet Kanhaiya.

کان فی الھند نبیاً اسود اللون اسمہ کاھنا

The “black Prophet” has been a cause of intrigue among Muslim scholars of all ages, but what made Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’sas interpretation stand out (and invited a huge outcry) was his assertiveness based on revelation, and his claim to be Krishna’s second advent. His Krishna-notion not only invited opposition from certain Hindu circles, but from his own coreligionists too.

Despite this vehement opposition of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, prominent Muslims continued to venerate Krishna as a saintly figure if not a Prophet. One noteworthy example from the post-Mirza Ghulam Ahmad period is Sayyid Fazl al-Hasan Hasrat Mohani, more commonly known as Maulana Hasrat Mohani in India’s independence history, and Urdu literature for his significant contribution to both.

Aside from his aforementioned claim to fame, Mohani was a devout follower of, first, the Qadiri order, then the Chishti-Sabri order, and then of both. He progressed in his affiliation with both the Sufi orders, becoming eligible to initiate people into both orders.

In his poetical collections (diwan), he opens the seventh Diwan with the following introduction:

“[…] I have occasionally mentioned in these verses the names of saintly elders [buzurg] from whom I have received spiritual boon [faiz]. In addition to the Islamic personages, I have also mentioned Sri Krishna. Concerning Hazrat Sri Krishna ‘aliahi r-rahmah [may blessings be on him], this faqir [mendicant; referring to one’s own self with humility] follows the path of his pir [spiritual mentor] and the path of pir of all pirs, Hazrat Sayyad Abdur Razzaq Bansawi, may Allah sanctify his innermost heart.”40

In these Bhasha/Krishna verses, we find devotional love expressed by Mohani for Krishna:

من تو سے پریت لگائی کنھائی

کاہو اور کی صورت اب کاہے کو آئی

“My heart has fallen in love with Kanhaiya; why should it think of anyone else”41

Almost all poems, what Mohani named “Bhasha/Krishna” poems and spread over diwans 7,8 and 9, carry passionate devotional expression of love for Krishna. Biographers of Hasrat Mohani take him to have believed in Krishna as a Prophet (rasul) of Allah.

Krishna’s romance continued to fascinate many a Muslim Sufi, thinkers and literati, the last example I refer to here being of Hafeez Jalandhari, more known as an activist of the Pakistan movement and the poet of Pakistan’s national anthem. He was a Hafiz-i-Quran (learnt Quran by heart) and is still classed as one of the orthodox Muslim poets of India and later Pakistan.

What is kept obscure from the general public is his devotional love for Krishna. His poem, Krishan Kanhaiya, speaks volumes of how he saw divine agency in the character of Krishna. I present here only the opening lines:

اے دیکھنے والو؛ اس حُسن کو دیکھو؛اس راز کو سمجھو؛یہ نقشِ خیالی؛یہ فکرتِ عالی؛یہ پیکر تنویر؛یہ کرشن کی تصویر؛معنی ہے کہ صورت؛صنعت ہے کہ فطرت؛ظاہر ہے کہ مستور؛نزدیک ہے یا دور؛

یہ نار ہے یا نور؛دنیا سے نرالا؛یہ بانسری والا؛ہے سحر کہ اعجاز؛کھلتا ہی نہیں راز؛کیا شان ہے واللہ؛کیا آن ہے واللہ؛حیراں ہوں کہ کیا ہے؛اک شانِ خدا ہے

“O viewers, look at this beauty and understand the secret, this imaginative art and the high thought behind it. This image of Krishna is light embodied. It is form and meaning imbued in craft of nature like an open secret. Mysteriously distant yet near, like fire and its light, this flute player is a strange being, like from some other world. His magic, his mystique, remains obscure; Praise be to God.”

Pakistan’s hardliner right wing could, of course, not tolerate the creator of Pakistan’s national anthem to have seen Krishna, a Hindu deity, worthy of veneration as a divinely appointed messenger; hence slipping it under the rug. We conclude this part with a few more lines that summarise the Krishna devotion of Muslim saints and thinkers:

بت خانے کے اندر

خود حُسن کا بت گر

بت بن گیا آکر

“Inside the temple; the sculptor of beauty himself; entered and became an idol.”

Jalandhari sums it all up here by stating that the one sent to introduce people to the beauty of God, was turned into a god through the devotional love of his followers. Sharjeel Imam and Saquib Salim, analysing Jalandhari’s poem, see him as reiterating “the age-old belief of a section of Islamic scholars, that Krishna was a righteous Prophet, sent to the people of the Subcontinent”.42

A poetic verse of Muhammad Iqbal, the Indian Muslim poet/thinker, must be mentioned here before moving on:

یہ آیۂ نو جیل سے نازل ہوئی مجھ پر

گیتا میں ہے قرآن، تو قرآن میں گیتا

“It has been revealed to me that Quran and Gita are one and the same”43

Polytheism in pre-Islamic Mecca

Before the dawn of Islam, we clearly know of the existence of four major religions in Arabia: Judaism, Christianity, Paganism, and Sabeanism. While the Holy Quran refers to the first three, the fourth is only sporadically touched upon.

The Quranic reference to Paganism too is not very defining of their belief, save their polytheistic practices and tendencies. What needs closer attention is where these kuffar (disbelievers) are mentioned as mushrikun – those who believe in other deities alongside God. The term mushrikun intrinsically indicates belief in God, alongside other gods; the mushrikun are recorded in the Holy Quran as saying:

وَقَالَ الَّذِیۡنَ اَشۡرَکُوۡا لَوۡ شَآءَ اللّٰہُ مَا عَبَدۡنَا مِنۡ دُوۡنِہٖ مِنۡ شَیۡ

“Those who set up equals [to Allah] say: ‘If Allah willed, we should not have worshipped anything beside Him […]”44

The Holy Quran further gives a hint into what the mushrikun believed:

وَلَئِنۡ سَاَلۡتَہُمۡ مَّنۡ خَلَقَ السَّمٰوٰتِ وَالۡاَرۡضَ وَسَخَّرَ الشَّمۡسَ وَالۡقَمَرَ لَیَقُوۡلُنَّ اللّٰہُ ۚ فَاَنّٰی یُؤۡفَکُوۡنَ

“And if you ask them, ‘who has created the heavens and the earth and pressed into service the sun and the moon?’, they will surely say, ‘Allah’; How then are they turned away from truth?”45

This verse, and quite a few more, indicate to a belief in a “high God”, but a belief in other gods as well. The mushrikun call for help to this Supreme God, Allah, in times of distress and, once relieved, turn back to His rivals (andaad).

As discussed, the monotheistic origins of Hinduism remained an intriguing domain for Muslims across the centuries to follow, more so in the latter part of the 19th and early parts of the 20th century.

Hinduism, even in its modern forms, maintains a belief in a Supreme God, Brahman, termed in Sanskrit terminology as Svayam-Bhagvan or “God Itself”; or Para-Brahman, meaning “Supreme Being”.

We have already spoken of the possible origins of Hinduism in one of the early Monotheistic laws (sharias) mentioned in the Holy Quran – that of Noahas or Abrahamas – and as being one of the many tributaries of Sabeanism. The idolatry that made its way into this originally monotheistic belief is what turned it into, as Max Muller would call it, Henotheism. Verses of the Rigveda, for instance, mention multiple deities, but consolidate them into the One God46 – ekam to remain literal in Sanskrit, and Tawhid in Arabic.

We can imply from the Quranic description of Arab pagans as being somewhere in the middle of strict monotheism and polytheism. This, as we have discussed above, was and is the case with Hinduism. And it is this form of polytheism that is quite expressly addressed in the Holy Quran:

وَجَعَلُوۡا لِلّٰہِ مِمَّا ذَرَاَ مِنَ الۡحَرۡثِ وَالۡاَنۡعَامِ نَصِیۡبًا فَقَالُوۡا ہٰذَا لِلّٰہِ بِزَعۡمِہِمۡ وَہٰذَا لِشُرَکَآئِنَا ۚ فَمَا کَانَ لِشُرَکَآئِہِمۡ فَلَا یَصِلُ اِلَی اللّٰہِ ۚ وَمَا کَانَ لِلّٰہِ فَہُوَ یَصِلُ اِلٰی شُرَکَآئِہِمۡ ؕ

“And they have assigned Allah a portion of the crops and cattle which He has produced, and they say, ‘This is for Allah,” as they imagine, ‘and this is for idols [that we associate with Allah]’; But that which is for their idols reaches not Allah, while that which is for Allah reaches their idols […]”47

Hindu traits of associating gods with The God can be identified in the Quranic subliminal description of paganism:

لَمۡ یَلِدۡ وَلَمۡ یُوۡلَدۡ وَلَمۡ یَکُنۡ لَّہٗ کُفُوًا اَحَدٌ

“He begets, not is he begotten; and there is none like unto Him”48

Similarly, gender diversity in these pagan gods, again identifiable in Hindu gods and goddesses, is quite clearly mentioned:

وَجَعَلُوۡا لِلّٰہِ شُرَکَآءَ الۡجِنَّ وَخَلَقَہُمۡ وَخَرَقُوۡا لَہٗ بَنِیۡنَ وَبَنٰتِِ بِغَیۡرِ عِلۡمٍ

“And they hold the jinn to be partners with Allah, although He created them; and they falsely ascibe to Him sons and daughters without any knowledge […]”49

Best known of such deities are named in the Holy Quran as al-Lat, al-Uzza and al-Manaat – asking the pagans how they associate these deities with God, and that too as His daughters.50

Further strengthening the Hindu influence on Arab paganism are the depictions of al-Lat, al-Uzza and al-Manat. Discovered from the 5th temple at Hatra (Ninawa Governorate, Iraq) dating back to 1st – 3rd centuries CE, all three are seen together, dressed like Indian goddesses; also quite similarly, with their right hands raised to their shoulders with the palm showing.

Rashid al-Din Hamdani, the Ilkhanid vizier and historian, noted in his book Tarikh-i-Hind (History of India) that Indian religions had great influence on Arab pagans and that “people of Mecca and Medina and some Arabs and Persians followed the religion of Shakyamuni before Islam”; and that “there were idols in the idol house [Kaaba] in the shape of Shakyamuni in front of which they bowed down.”51

The teachings of Sakyamuni, or Gautama Buddha, had thus reached Arabia in their non-monotheist form and had found compatibility with the pagans. The Buddha too is believed by a number of Muslim scholars to have been a Prophet. Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (1928-2003), the fourth Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, is not alone in stating that Buddha is listed among Prophets in the Holy Quran by the name of Dhul-Kifl – Kifl being the Arabicised name of his birthplace, Kapeel.52 Historian WH Siddiqi, tracing Indian influence on Arabia, asserts the same.53

Another 11th-century historian, Abu Said al-Gardizi, describing the temple of Somnath, wrote that “it contained […] the idol of Manat, which had been transported from the Ka’ba by way of Aden in the time of the Lord of the World [Prophet Muhammadsa].”54

The traders and merchants from al-Hind, who were adherents of the Hindu faith or its derivatives, must have brought along their own idols to place in and around the Kaaba. They were travelling merchants and would stay away from their homes and temples for months or even years on end. The presence of Hindu idols and their influence on Arabian paganism is quite a plausible fact.

The Quranic term Ahl al-Kitab, or people of the Book, has thus to be understood in a broader sense that encompasses all major religions that existed in Arabia, in whatsoever distorted shape or form, at the eve of Islam. The Kaaba had gained the status of a multi-faith sanctuary that hosted all types of idols and symbols of a variety of faiths. Hindu idolatry had hence left a deep mark on pagan beliefs, and it was this atmosphere that faced the dawn of Islam in Arabia.

We close this part by quoting al-Shahrastani on the similarities between the pagans and Hindus:

“The Arabs [pagans] and Indians converge on one doctrine. Their greatest inclination is towards determining the properties of things, judging by rulings, the essence of facts and practising spirituality.”55

Thus, the immediate audience of the Holy Prophetsa, when commissioned with prophecy, were the Jews, Christians and a great variety of pagans who had gone astray from their monotheistic beliefs of one time and now worshipped gods alongside the One God.

The Holy Prophetsa and al-Hind

It is reported in Hadith that the Holy Prophetsa would say, “I feel a cool breeze coming from Hind.”56

While this hadith may be put through scrutiny in the midst of the current political conflict between India and Pakistan, there is a lot more to suggest that al-Hind had a special place in the imagination of the Holy Prophetsa. To avoid any misgivings, it must be clear that al-Hind does not refer to modern-day India alone, but the entire Indian Subcontinent as it existed in the time of the Holy Prophetsa.

Whatever the case, we know with as much certainty as possible from hadith and sirah literature, that al-Hind was known to the Prophet through its incense trade – that kept the heart of Meccan trade beating – and also through the weaponry manufactured there and sold in Arabia.

There are only a few geographical areas mentioned in the hadith literature, al-Hind being one from among bilad Arab, bilad Rum, al-Maghrib, al-Mashriq, and al-Habsha. Out of all, al-Hind seems to find the most mention, with a sense of mystique and intrigue, owing to a great deal of myth attached to it.

We know that at the time of the Holy Prophet’ssa birth, Mecca was an established mercantile town where Indian swords were a precious commodity. Born in a family that managed all this trade, he must have been acquainted with the Saif Hindi – the Indian sword – from early childhood. Not forgetting that the family remained occupied with war and defence at all given times.

Ibn Hisham reports that the Jurhum, as they fled Mecca upon defeat by Khuza, buried their treasures in the Zamzam well. The well remained concealed for centuries before Abd al-Muttalib, the grandfather of the Holy Prophetsa, traced it and dug it up. Initially done to reinstate the well as a water source, he discovered the treasures therein which, as Ibn Hisham’s report goes, had to be distributed among other leaders of the clan. Abd al-Muttalib is said to have received swords and other items of armour (ووجد فیھا اسیفا قلعیۃ و ادرعاً). 57 Qala’i, we have discussed above, was a name for the Indian swords.

As for day-to-day life in Mecca, Indian spices were a common commodity and comprised Arabic culinary, as we have already discussed, so much so that they are mentioned by their Sanskrit names, albeit in Arabicised form: Zanjabil (ginger), kafur (camphor, kapur), and mushka (musk).58

The Holy Prophetsa mentioned these products of Indian origin in several traditions. Musk for him is the best fragrance,59 the fragrance of a martyr’s blood and that of a fasting person’s breath, and as good as the company of a righteous person. His Companions and family have reported on his fondness for using musk.

Oud Hindi (aloes- and agarwood) appears as one of his favourite incenses, which he burnt along with kafur (camphor).60 Abdullah ibn Umarra perfumed himself with oud on its own, and sometimes used kafur on top of it, saying that the Holy Prophetsa perfumed himself thus.61 He prescribed the use of Oud-Hindi as medicine for various ailments.62

Abu Said al-Khudrira narrates that a raja from al-Hind sent zanjabil (ginger) as a gift to the Holy Prophetsa, which he distributed among his Companions and consumed some himself.63

We have already seen how people from al-Hind and al-Sind had settled in various parts of Arabia, especially along the coastal regions. It is established from various Hadith and sirah literature that the Holy Prophetsa was well acquainted with these people.

The Holy Prophetsa sent Khalidra ibn al-Walid to invite the people of Najran to Islam. Ibn Hisham reports that upon his success, Khalidra returned to Medina with a group of these people. Upon seeing them, the Holy Prophetsa enquired, “Who are these people that resemble the people of al-Hind?”64

While this shows that the Holy Prophetsa was very much aware of the people of al-Hind, it also goes to prove the presence of such people in the southern parts of Arabia.

Upon his experience of Mi‘raj, the Holy Prophetsa described Mosesas as having features of the Zutt people, who, we have discussed earlier, were people from the lands of al-Hind. 65

Abdullah ibn Masudra narrated in a long report that on the night the Holy Prophetsa met the jinns, he had accompanied the Holy Prophetsa. He was told to remain confined in an area and not leave it whatsoever happens. While the Holy Prophetsa was away, the jinns came quite close to Abdullah ibn Masudra who identified them as Zutt.66

In Medina, Aishara fell ill and is said to have been treated by a physician who was from the Zutt. Although this incident is from after the demise of the Holy Prophetsa, it still shows the presence of people from al-Hind in Medina.67

Now we have three elements of al-Hind around the Holy Prophetsa: Indian swords, Indian incense, and people of Indian origin. All these find a fair share in the Holy Prophet’ssa description of the apocalypse, or, as the genre is called, Islamic eschatology.

Al-Hind in the latter-day imagination of the Holy Prophetsa

It appears that al-Hind in the imagination of the Holy Prophetsa, as with other Arabs of his times, was a very peculiar place. He associated with it incense and warfare, both. He is reported to have said:

“I feel a cool breeze coming from al-Hind.”68

While this tradition always carried a romance in it for Muslims, the current geopolitical tensions in the region of al-Hind – Pakistan and India – have led to Pakistani scholars most vehemently rejecting the authenticity of this hadith.

It is as sad as interesting to note how hadith literature is kept fluid so as to serve desired political purposes in any given time and circumstances. Sir Muhammad Iqbal, generally and almost unanimously accepted by South Asian Muslims as a great Muslim thinker, found this hadith sound enough to allude to it in his verse:

میرِ عرب کو آئی ٹھنڈی ہوا جہاں سے

میرا وطن وہی ہے، میرا وطن وہی ہے

“From where reached cool breeze to the lord of Arabia; that is my homeland, indeed it is.”69

Was this cool breeze from a land that the Holy Prophetsa believed to be the homeland of Adam, or was he referring to the signs of a breeze that was yet to blow from al-Hind towards Arabia? No one can say with certainty, but one can further investigate, although by way of speculation.

Another tradition has it that the Holy Prophetsa stated, “I am an Arab, but Arabia is not in me; I am not from al-Hind but al-Hind is in me.”70

Stalwarts of South Asian Islam like Shah Waliullah Muhadith Dehlvi, found this very tradition to be sound enough that he applied it in his revivalist polemics.

Thus far, we see hope and anticipation in the Holy Prophet’ssa imagination of al-Hind. This element of hope is disturbed by a great war, yet only to be revived in the aftermath.

Ghazwa-e-Hind, or the Indian war, makes up part of eschatological Hadith literature. This war is mentioned primarily in Sunan al-Nisa’i, later to be quoted and alluded to through Hadith literature that emerged through the centuries to follow. While al-Nisa’i notes only three variants of transmissions, he dedicates a chapter titled exclusively as “Bab Ghazwa-t al-Hind”. It is best to first see the wording of the tradition, and its variant, before moving on:

- There are two groups of my Ummah whom Allah will free from the Fire: The group that invades al-Hind, and the group that will be with Isa ibn Maryam.71

- We will invade India. If I live to see that, I will sacrifice myself and my wealth. If I am killed, I will be one of the best of the martyrs, and if I come back, I will be Abu Hurayrah and free of fire.72

Having remained acceptable to the likes of Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal and Ibn Kathir, the latter seeing it as already manifest in the conquest of India through Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712 CE, the tradition got to be either vigorously rejected or mercilessly misconstrued in the current India-Pakistan political tensions.

Radical Muslim circles in Pakistan jumped on to any such material, be it a hadith or any form of its interpretation, to justify their war (and militant struggles in Kashmir) against India. Indian Muslims have generally rejected not only the status of this hadith, but also any interpretation of it aimed at Islamising the current conflict.

The author is of the opinion, based on what has been presented above, that this hadith has absolutely no connection, in word or spirit, to any geopolitical tensions between India and Pakistan. However, the author is also inclined not to justify any outright rejection of the hadith itself, as the Isa ibn Maryam version is classed as hasan, i.e., one with the probability of being factual.

To gain a better understanding, we continue to look into the hadith further, placing the tradition against the aforementioned information and other historical facts that are yet to follow.

The Conquest of Mecca and Jabal Hindi

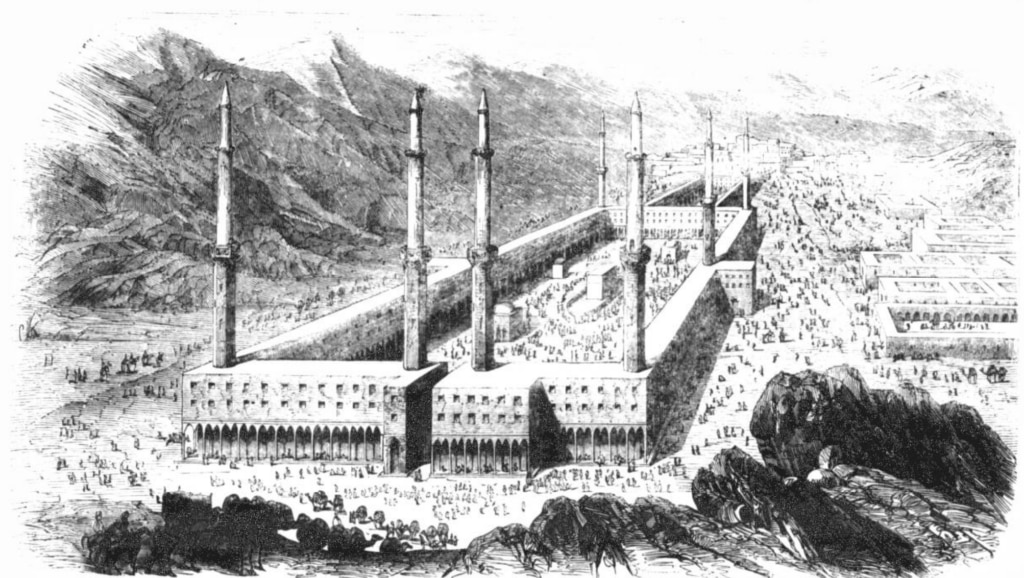

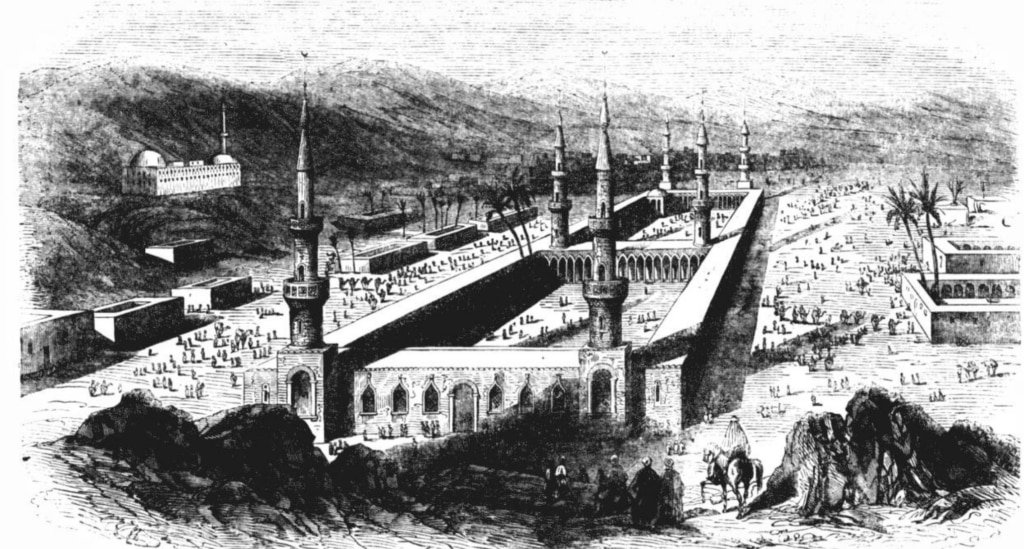

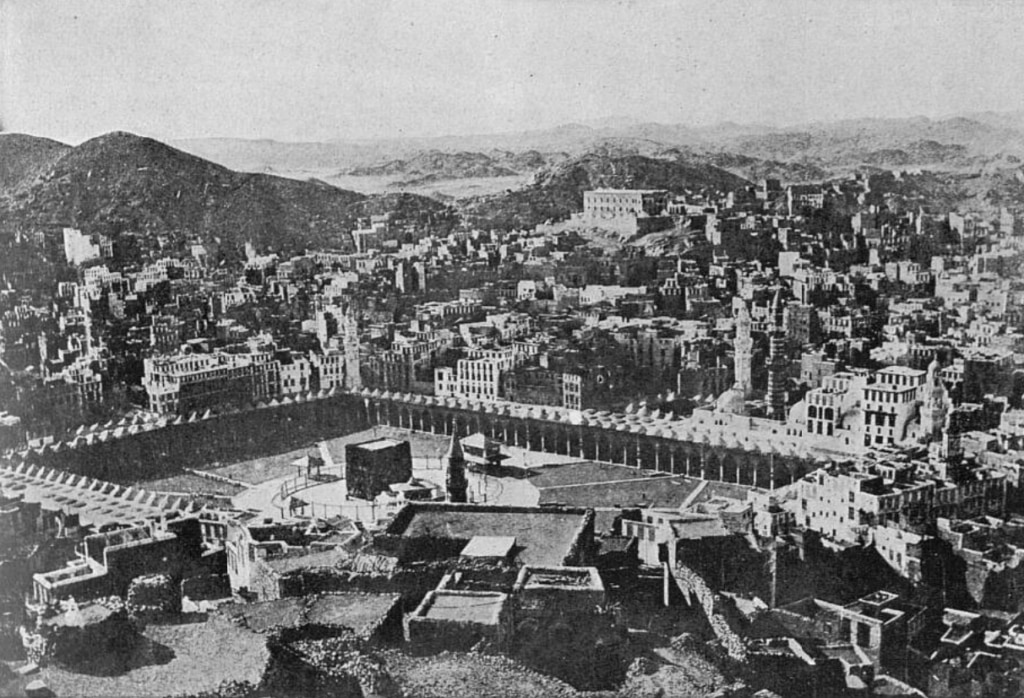

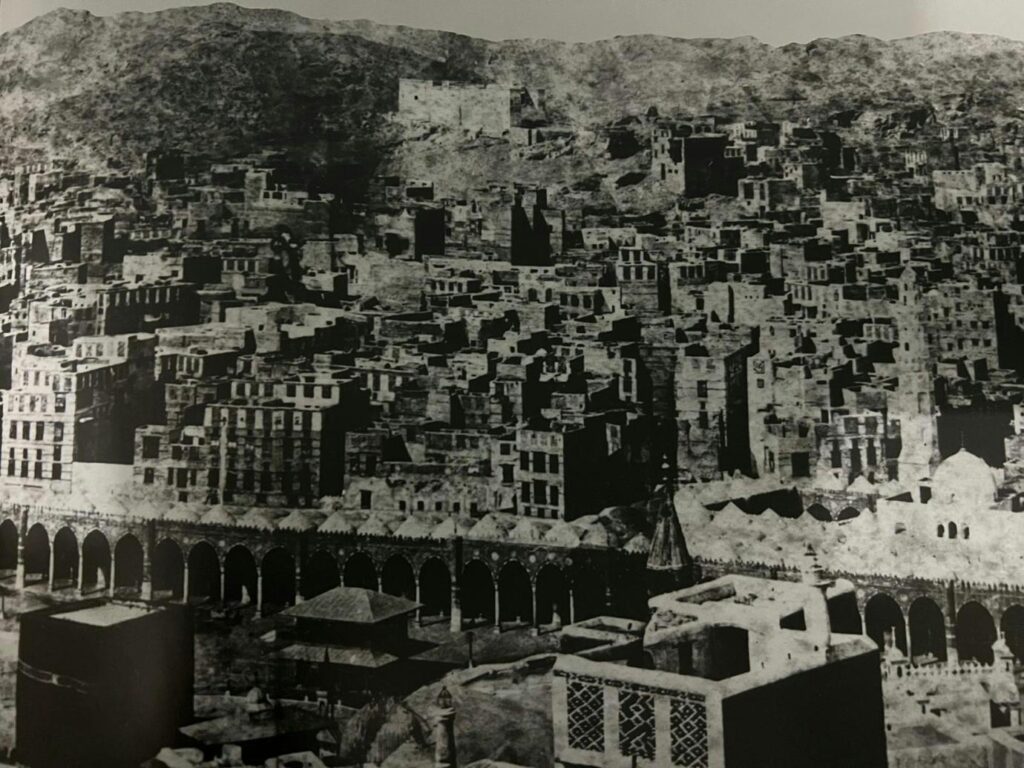

Coming back to where this study all started, we understand from various books of Islamic history that the Holy Prophetsa entered Mecca through the northern part of the town, through a passage called Kada‘ – the point where al-Akhshabayn meet. Al-Akhshabayn are the two sets of mountains that surround Mecca – Jabal Abu Qubays to the east and Jabal Qaiqaan (alt. Qayqa’an) to the west of the Kaaba.

Both ranges of mountains bracket the Kaaba and meet at the northern and the southern part of Mecca, forming a ravine at both ends – the northern one called Kada‘, the southern Kudai. The Holy Prophetsa, along with his army of around 10,000 men entered through Kada‘ and marched along the Qaiqaan range through Al-Zakhir (alt. Az-Zakhir, Azzakhir, Thakhar) all the way to the foot of Jannat al-Maala where he stationed himself at Jabal Hajun – overlooking the graves of his wife Khadijara, and uncle Abu Talib.

He split his army into four battalions led by his Companions, to enter Mecca from all four sides. He himself remained at the topmost mount of Qaiqaan, called Jabal Hindi; with the instruction that all battalions were to join him before the final descent into Mecca.

The primary motive behind my intrigue into this entire matter, that is, how Jabal Hindi got its name, was a puzzle to solve in its own right. For this, we have to go a long way back into history.

The Jurhum had attacked and taken control of Mecca from the Bani Ismael (the children of Ismaelas). They stationed themselves on Jabal Hindi in the Qaiqaan stretch of mountains. As a means of defence against contesting tribes like Qatura and Khuzaa, the Jurhum built a strong artillery of swords and arrows, both, as we know, imported from al-Hind.

Some think that the Himyarite King Tubba stored his Indian swords, or hindawiyyah, in this mountain and hence the name Jabal Hindi.

Located just beside the Kaaba, it made a perfect garrison as well as an artillery for the Hindi weapons to be stored, and hence got its name, Jabal Hindi. The clanking of these swords when the Jurhum and the Qatura had a decisive war that lent the name Qaiqaan to the entire range of hills that stretches from the west through the northwest of Mecca. The lowest point of Jabal Hindi is Jabal Marwa and is just beside the Kaaba.

The Holy Prophetsa made his victorious and triumphant descent into Mecca from Jabal Hindi, and approached the holy Kaaba from the nearest point, which is thus called Bab al-Fath (the victory gate).

Jabal Hindi was, much later, to gain great historic importance by housing a citadel known as Qil‘a Hindi, in Ottoman times. This fortress served the purpose of defending Mecca from any foreign attacks, which it was much prone to.

After the Ottomans were driven out of Mecca, the fortress was turned into The Sharia College in 1949, which later evolved into what is now Umm al-Qura University in 1981 – the first university to be established in the Holy Prophet’ssa hometown.

The same Qil‘a Hindi was used to broadcast radio signals in Saudi Arabia for the first time ever through the radio station named Huna Macca-t al-Mukarramah, or “This is the Noble Mecca.”73 This historic event, where the verses of the Holy Quran were broadcast through radio for the first time in Mecca, happened on the day of Arafat, 9 Dhul Hajjah, 1368 H (1948 CE).74

So it was this mountain, Jabal Hindi, that the Holy Prophetsa chose to step into Mecca as a victorious general of the triumphant army of Islam.

He must have had the history of Jabal Hindi in mind – and the swords from al-Hind that lent it its name. He and his army were carrying these Hindi swords themselves for this most magnificent victory of his prophetic mission – it was, after all, the House of Allah coming into the fold of Islam. His first task here was to cleanse the Kaaba of all idols, which he carried out before performing its tawaf.

He must have had the future of Islam in mind too – the ghazwa-t al-Hind. The idols that he cleansed the Kaaba of had arrived from al-Hind over centuries and had the potential to make their way back into the heart of Islam, from all various tracks and in all various shapes and forms. We know from his traditions that he had envisaged his Ummah coming under attack by various religions. He foretold how his Ummah would split into many sects like the Jews, come under the influence of Christianity, and also warned the Ummah to abstain from idolatry creeping back into their faith.

Was this the backdrop against which he mentioned the ghazwa-t al-Hind – the great war of India? The Indian Subcontinent had developed into a melting pot of most religions alongside being the home of the idol-worshipping majority population.

In a time when religious wars had shifted to battlefields of discourse and debate, was al-Hind again going to provide the sword of argument? Was al-Hind once again going to house the fort for the defence of Islam? Of the two groups that were promised protection from fire, one was to fight this war, and one was to be with Isaas ibn Maryam, the Promised Messiah. Was the Messiah of the latter days to have such a close connection to al-Hind? Just like his earliest predecessor, Adamas, was the Promised Messiahas of the Latter Days to descend in al-Hind and defend the heartland of Islam? Technically speaking, a ghazwah is a war in which the Holy Prophetsa participated personally. For the ghazwa-t al-Hind, was it to be a second manifestation of the Holy Prophetsa, or was the Messiah to represent him?

Without forcing any conclusion on my reader, I wish to conclude with these questions for them to ponder, reflect on, and reach conclusions of their own.

1 W. F. A. Jamme, The Al-‘Uqlah Texts (Documentation Sud-Arabe, III), Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1963, as quoted in:Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987, p. 169

2 For detailed information on this period, see L. A. Waddell, The Indo-Sumerian Seals Deciphered: Discovering Sumerians of Indus Valley as Phoenicians, Barats, Goths & famous Vedic Aryans 3100-2300 BC, Luzac & Co, London, 1925

3 As defined by the Oxford Centre for Late Antiquity

4 Ibn Khordadbeh, Al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik

5 “Indian Migration to the Gulf Countries: Past and Present”, Prakash C. Jain, India Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 2 (April-June, 2005), pp. 50-81

6 Ibn Manzur, “زط”, Lisan al-Arab, Beirut: Dar Sad, Vol. 7, p. 308

7 Muhammad Tahir, Majma‘ Bihar al-Anwar fi Ghara’ib al-Tanzil wa Lata’if al-Akhbar, Vol. 2, Hyderabad: Majlis Da’irat al-Ma‘arif al-‘Uthmaniyya, 1967 CE, p. 424; Fakhr al-Din Muhammad ibn ʿAli al-Turayhi al-Najafi, Majmaʿ al-Bahrayn wa Matlaʿ al-Nayyirayn, Vol. 2, p. 276

8 Abu al-Fida, Taqwim al-Buldan, 355, Dar Sadir, Beirut,

9 Al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik, p. 35; Ibid., p. 56

10 Ibid.

11 George Rawlinson, The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World: The History, Geography, and Antiquities of Chaldaea, Assyria, Babylon, Media, Persia, Parthia, and Sassanian or New Persian Empire, Worthington Co, New York

12 Ibid.

13 Sabir Badalkhan, “Coastal Makran as Corridor to the Indian Ocean World,” Eurasian Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2002), pp. 237–262; André Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Volume I: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries, Brill, 1990, Chapter IV: “The Frontier of al-Hind,” pp. 109–218

14 Futuḥ al-Buldan, p. 367

15 Ibid.

16 al-Idrisi, Nuzhat al-Mushtaq

17 Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.63; Surah al-Ma’idah, Ch.5: V.69; Surah al-Hajj, Ch.22: V.18

18 I have intentionally avoided the term “polytheists” for the mushrikun, as it does not strictly mean associating gods with God, but worshipping multiple gods.

19 Surah ar-Ra‘d, Ch.13: V.8

20 Ibid.; Surah ash-Shura, Ch.42: V.14; similar classification of the four Prophets is found in Surah al-Ahzab, Ch.33: V.8

21 Stephen Hillyer Levitt, “Vedic–Ancient Mesopotamian Interconnections and the Dating of the Indian Tradition,” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 93 (2012), pp. 137–192.

22 Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, 3 volumes, University of Chicago Press, 1974

23 Tarikh Ferishta, Vol. 2, p. 604

24 Surah al-An‘am, Ch.6: V.75

25 Rigveda, 7.97b

26 Genesis, 17:5

27 Sama Veda, 96.2

28 Genesis, 20:14

29 Ibid., 21:5

30 RV, 3.23.1; AV, 19.42.2

31 Genesis, 22:1-13

32 Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni, Alberuni’s India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about A.D. 1030, Translated by Edward C. Sachau, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., London, 1910

33 Abu al-Fath al-Shahrastani, Kitab al-Milal wa al-Nihal, Part 2, tr. W Cureton, London, 1842

34 Al-Gardizi, p. 98

35 Surah al-Waqi‘ah, Ch.56: V.78-80; Dara Shukoh, Sirr-i-Akbar, edited by Tara Chand and Sayyid Muhammad Riza Jalali Naini, Taban Printing Press, Tehran, 1957

36 Naimullah Bahraichi, Basharat-i Mazhariyya dar Fazail-i Hazarat-i Tariqiya-i Mujaddidiyya, compiled letters of Mirza Mazhar Jan-i-Janan, Ms. IOR/4431

37 Ibid.

38 Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, Malfuzat, Vol. 10, 1984, p. 143

39 Kenneth Cragg, Counsels in Contemporary Islam, Islamic Surveys No. 3, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1965, p. 156

40 Kulliyat-i-Hasrat Mohani, Sheikh Ghulam Ali Publishers, Lahore, 1964

41 Ibid., Diwan, p. 8

42 Sharjeel Imam and Saquib Salim, “In pre-partition India, Muslims too celebrated Janmashtami: A look back at the reverence for Krishna in works of Urdu poets,” Firstpost, published 14 August 2017, accessed 9 January 2025

43 Muhammad Iqbal, Bang-e-Dara (The Call of the Marching Bell), 1924

44 Surah an-Nahl, Ch. 16: V.36 (bold emphasis by author)

45 Surah al-‘Ankabut, Ch. 29: V.62

46 Rigveda, Book 5, Hymn 3, Verses 1-2

47 Surah al-An‘am, Ch.6: V.137

48 Surah al-Ikhlas, Ch.112: V.4-5

49 Surah al-An’am, Ch.6: V.101

50 Surah an-Najm Ch.53: V.20-21

51 Tarikh-I Hind, Chapter 20

52 Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh, An Elementary Study of Islam, Islam International Publications Ltd., 1997, p. 24

53 W. H. Siddiqi, “India’s Contribution to Arab Civilization,” in India’s Contribution to World Thought and Culture, edited by Lokesh Chandra, Madras: Vivekananda Rock Memorial Committee, 1970, p. 586

54 Abu Sa‘id ‘Abd al-Hayy Gardizi, The Ornament of Histories: A History of the Eastern Islamic Lands AD 650–1041, Translated and edited by C. Edmund Bosworth, I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 96.

55 Kitab al-Milal wa al-Nihal, Vol. 1, p. 2-3

56 Al-Hakim al-Nishapuri, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala al-Sahihayn, Hadith 4056

57 Ibn Hisham, Sirat Rasul Allah, Vol. 1, p. 146.

58 Sayyid Sulaiman Nadvi, Arab Wa Hind Ke Taalluqat, Hindustani Academy, Allahabad, 1930

59 Sahih Muslim, Hadith 2252b

60 Kunz-ul-Ummal, Kitab shamaili n-nabi

61 Mishkat, Hadith 4436

62 Tirmidhi, Hadith 952; Abu Dawud, Hadith 3877

63 Al-Hakim al-Nishapuri, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala al-Sahihayn, Kitab al-at‘imah, Dhikru ihda’i maliki l-hindi z-zanjabila ila n-nabiyy, Hadith 7272

64 Ibn Hisham, As-Sirah an-Nabawiyyah, Volume 2, p. 593; Al-Tabari, Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk, Volume 3, p. 157

65 Sahih al-Bukhari, Kitab ahadithi l-’anbiya, Hadith 3438

66 Tirmidhi, Kitab al-’amthal, Hadith 2861

67 Al-Adab Al-Mufrid, p. 27

68 Al-Hakim al-Nishapuri, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala al-Sahihayn, Hadith 3954

69 Muhammad Iqbal, Bang-e-Dara

70 Hakim, Al-Mu‘jam al-Awsat

71 Sunan an-Nisa’i, Kitab al-jihad, Bab ghazwati l-hind, Hadith 3175

72 Ibid., 3173

73 Fauzi bin Muhammad bin Abdahu Sa’ati, Harat al-Shamiyyah (Al-Shamiyyah Neighbourhood), Jamia Umm al-Qura, 2011, p. 59

74 Ahmad bin Muhammad al-Maghribi, al-Inayat bil-Quran al-Karim fi Makka-t al-Mukarramah, p. 136