Iftekhar Ahmed, Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

I. Introduction

The concept of ilzam, often employed by the Promised Messiah, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas (d. 1326/1908), represents a significant aspect of his argumentative strategy, especially when engaging with opponents in both direct debates and theoretical discussions. This concept, represented by the Arabic term ilzam – which gave rise to the Urdu expression ilzami jawab commonly used in the Indian subcontinent – has unfortunately been subject to misinterpretation and controversy, leading some critics to erroneously accuse the Promised Messiahas of blasphemy.

Moreover, the Urdu expression ilzami jawab has often been mistranslated as “accusatory response,” a misconstruction that is not only inaccurate but also misleading, as it suggests a focus on personal attacks rather than logical argumentation. To understand the true meaning of ilzam, we must turn to its Arabic roots. The term derives from the verb alzama, meaning “to compel” or “to obligate.”

This concept is known in the Western logical tradition as argument from commitment (argumentum ex concessis). Unlike, for instance, the ad hominem fallacy, which attacks the person making the argument, argumentum ex concessis, when properly employed, is a valid form of argumentation with a long and distinguished history. It seeks to reveal inconsistencies within an opponent’s position by utilising their own statements and beliefs as premises, targeting the logical coherence of their stance, not their character.

This paper aims to clarify the true meaning and significance of ilzam, situating its usage within the broader context of Islamic intellectual history and demonstrating its connection to established principles of theological debate. The paper will begin by exploring the historical and philosophical underpinnings of ilzam, particularly its relationship to the Western concept of argumentum ex concessis. It will then examine the application of ilzam within Islamic scholarship, drawing on a wide range of sources to establish its legitimacy as a tool of theological discourse. Finally, the paper will discuss the Promised Messiah’sas views on, and justifications for, the use of ilzam, demonstrating that his approach to this technique was consistent with established Islamic scholarly traditions and refuting the accusations of blasphemy.

II. Philosophical and historical roots of argumentum ex concessis

The practice of employing an opponent’s concessions to reveal inconsistencies within their own position has a long history in Western philosophical thought. This technique, known as argumentum ex concessis, forms the basis of the approach we are discussing here.

II. A. Illustrating argumentum ex concessis: A simple example

To illuminate the concept of argumentum ex concessis, let us consider a simple, everyday example:

“Here is a very simple example. There will be eleven people for lunch. The maid exclaims, ‘That’s bad luck!’ Her mistress is in a hurry, and replies, ‘No, Mary, you’re wrong; it’s thirteen that brings bad luck.’ The argument is unanswerable and puts an immediate end to the dialogue.” (Chaim Perelman; L. Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, p. 111)

This short dialogue neatly demonstrates the principle of argumentum ex concessis in action. The maid, by expressing her belief in the bad luck associated with the number eleven, inadvertently concedes to a broader premise: that numbers can influence fortune. The mistress strategically utilises this implicit concession to counter the maid’s specific claim, redirecting the focus to a different number, thirteen, without necessarily endorsing the underlying belief in numerology.

The effectiveness of the mistress’ argument hinges entirely on the maid’s acceptance of the initial premise – that certain numbers are inherently unlucky. If the maid does not genuinely hold this belief, the argument loses its persuasive power. This example illustrates the key mechanism of argumentum ex concessis: leveraging an opponent’s pre-existing beliefs or concessions to support a different, often unintended, conclusion.

II. B. Formal dialectical systems and counterfactual conditionals

In formal dialectical systems, commitment to a proposition and its logical progression are central. The proponent’s role is to defend their thesis using premises that the opponent has already accepted, while both participants strive to maintain consistency in their positions. Should the opponent’s commitments logically support the proponent’s thesis, the opponent is obligated to either accept the conclusion or revise their prior commitments. Likewise, if a contradiction emerges between the proponent’s thesis and their original premises, they must adjust their stance accordingly. This approach requires the opponent to confront the logical implications of their own assertions, highlighting inconsistencies without introducing external assumptions. This method not only exposes logical flaws but also challenges informal fallacies, such as the straw man fallacy, where incorrect or exaggerated positions are attributed to the opponent.

From a formal perspective, an ex concessis argument is structured to establish a counterfactual conditional, where the antecedent includes the premises and the consequent is the argument’s conclusion. This method hinges on the proponent demonstrating that the opponent’s commitment logically extends to the new conclusion. If this inference fails, the argument collapses. Within dialectical exchanges, this technique pressures the opponent to uphold consistency, revealing contradictions that force them to either accept the conclusion or revise their stance. While inherently sound, this approach may be misused if the proponent exaggerates or distorts the opponent’s position.

II. C. Further distinctions within argumentum ex concessis

In Western logic, what is called an argument from commitment rests on the premise that if someone (“a”) is committed to a proposition (“A”) – either generally or based on their previous statements – then they are logically bound to support “A.” This type of argument aims to expose any inconsistencies between a person’s past statements and their current stance.

Argumentum ex concessis specifically refers to a style of argumentation tailored to an opponent’s particular claims. Here, one party may cite a statement made by the opponent, either to refute it directly or to highlight contradictions with other of the opponent’s assertions. This approach demonstrates inconsistency and serves to undermine the credibility of the opponent’s overall position.

Another relevant scenario involves using an opponent’s views to argue for one’s own position. In this case, a person leverages premises they do not necessarily endorse but which they assume the opponent finds convincing. For example, even without believing in spiritualism or vegetarianism oneself, one might employ principles from these doctrines when debating an adherent of one of these beliefs.

II. D. Early examples of argumentum ex concessis

Socrates (d. 399 BCE) used a questioning method known as elenchus to expose contradictions in his interlocutors’ beliefs. Through carefully guided questions, he led them to conclusions that conflicted with their accepted premises, not to impose a particular viewpoint but to encourage deeper reflection on their beliefs.

A similar approach appears in the work of Zeno of Elea (c. 430 BCE), a student of Parmenides (d. ca. 460/455 BCE), who defended Parmenides’ philosophy, notably his denial of motion. Zeno’s hypothetical arguments illustrated how accepting the concept of motion led to contradictions and absurdities. For instance, Zeno argued that if “the things that are” are indeed many, they must simultaneously be both like and unlike – an impossible outcome: “For neither can unlike things be like, nor like things unlike.” (Plato, Parmenides, 127e).

Though Zeno’s arguments may not have reflected his personal views on reality, his purpose was strategic: he sought to challenge the underlying assumptions of Parmenides’ opponents by revealing the inherent contradictions within them. Zeno’s dialectical refutations likely focused solely on exposing these contradictions, without delving into descriptions of the world beyond what aligned with Parmenides’ philosophy.

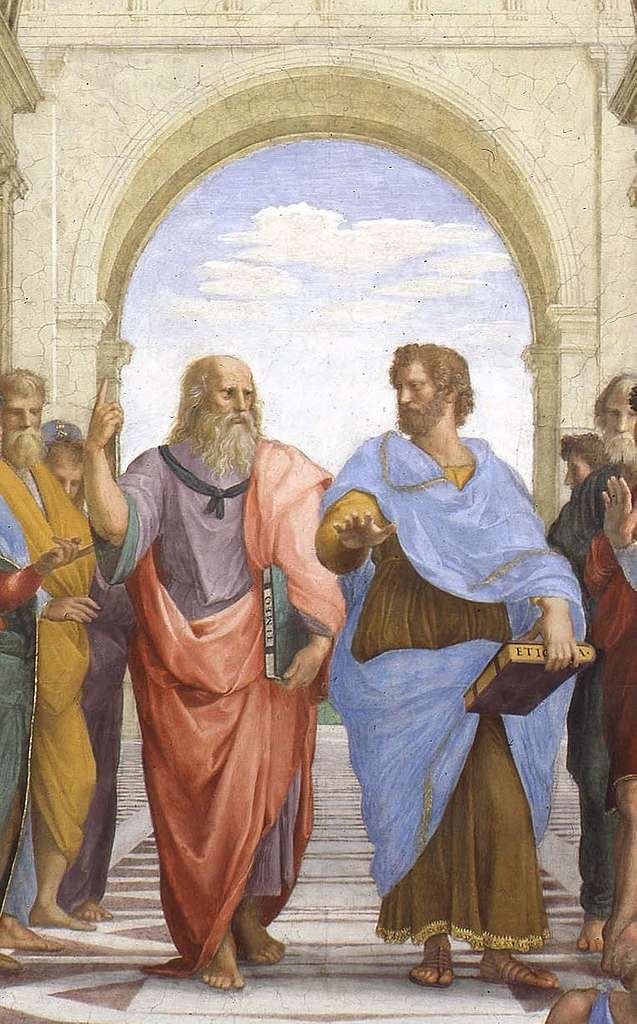

II. E. Aristotle: Formalising dialectic

Aristotle (d. 322 BCE), recognising Zeno as a pioneer of dialectic, formalised this argumentative technique. Aristotle’s dialectic, as elaborated in his Topics, involves arguing from commonly held beliefs to expose their inadequacy or falsehood. This method, distinct from his demonstrative logic, relies on the opponent’s own premises, not on empirically proven facts. This method of argumentation, deeply rooted in dialectical reasoning, involves revealing contradictions within an opponent’s position by employing their own accepted premises:

“It is in like manner necessary also when the questioner, having reached a certain point through induction by means of the view which his opponent has set forth, then attempts to demolish that point; for, if this has been demolished, the view originally set forth is also demolished.” (Aristotle, Topics, 112a)

He also advocates for a strategic, even indirect approach when constructing a refutation:

“Next, do not put forward the thing you actually need to obtain, but rather something which this follows of necessity. For people more readily agree because it is not equally evident what is going to follow from this, and when the latter has been obtained, the former has also.” (Ibid., 156b)

In his Sophistical Refutations, Aristotle underscores the importance of identifying contradictions:

“Moreover, as in rhetorical arguments, so likewise also in refutations, you ought to look for contradictions between the answerer’s views and either his own statements or the views of those who are generally held to bear a like character and to resemble them, or of the majority, or of all mankind.” (Aristotle, Sophistical Refutations, 174b19-23)

Aristotle’s focus on inconsistencies between statements and actions in this quote reflects the ancient Greek emphasis on living virtuously. In this tradition, a philosopher’s personal conduct is relevant to evaluating their ideas since philosophies aim to guide good living. Therefore, discrepancies between a philosopher’s principles and practices legitimately challenge their arguments, as seen in Aristotle’s virtue ethics. In contrast, modern philosophy’s more scientific approach often separates a thinker’s personal life from the evaluation of their theories. However, in ethical theories designed to guide behaviour, the justification is still tied to the proponent’s actions, especially within a virtue ethics framework. Thus, assessing ex concessis arguments remains linked to Aristotelian virtue ethics.

He further refines this approach in Prior Analytics, stating that if an opponent concedes a proposition that logically leads to a conclusion contradicting their stance, a refutation is inevitable:

“Hence if the admitted proposition is contrary to the conclusion, refutation must result, since refutation is a syllogism which proves the contradictory conclusion.” (Aristotle, Prior Analytics, 66b11)

Aristotle reiterates this approach in his Rhetoric, where he advises refuting an opponent by finding discrepancies between them and their statements:

“Another line is to refute our opponent’s case by noting any disagreements: first, in the case of our opponent if there is any disagreement among all his dates, actions, and statements.” (Aristotle, Rhetoric, 1400a15)

The strategic use of an opponent’s concessions also appears in Metaphysics, where Aristotle differentiates between proof and refutation:

“I mean ‘proving by way of refutation’ to differ from ‘proving’ in that, in proving, one might seem to beg the question, but where someone else is responsible for this, there will be a refutation, not a proof.” (Metaphysics, 1006b15-18)

Furthermore, Aristotle acknowledges that some arguments may be refuted not by direct evidence but by illustrating contradictions within an opponent’s stance:

“About such matters there is no absolute proof, though there is proof ad hominem.” (Metaphysics, 1062a2-3)

Aristotle in his above discussion of the principle of non-contradiction distinguishes “absolute proof” (haplos apodeixis) from “proof ad hominem” (Greek pros ton de apodeixis), i.e., proof relative to this person.

In Western thought, to argue ad hominem originally meant to use the concessions of an interlocutor as a basis for drawing a conclusion, thus forcing the interlocutor either to accept the conclusion or to retract a concession or to challenge the inference.

II. F. Later developments and interpretations

The concept of argumentum ex concessis evolved significantly through the works of later thinkers. Boethius (d. 524 CE) introduced the term disputatio temptativa, describing an argument where the speaker leads the opponent to a conclusion based on their own accepted premises. He explains that disputatio temptativa uses premises the opponent accepts or, at least, claims to know:

“[Disputatio temptativa are] those arguments that reason from premises which are accepted by the answerer and which anyone who pretends to possess knowledge of the subject, is bound to know. (Temptativa <est>, uit ait Aristotiles, que sillogizat ex his que videntur respondenti, et necessarium | est ei qui simulat se habere scientiam.)” (Boethius, Summa I, p. 275)

He further elaborates on the form of disputatio temptativa:

“The form of the temptativa is that he must […] return to the first premise, and from that, along with others that have been conceded, infer what one intends to prove. (Forma temptativa est quod debet […] reverti ad primam et ex illa atque aliis sibi concessis inferat quod intendit probare.)” (Ibid., p. 277)

In Europe, confusion regarding terminology arose early on, with argumentum ex concessis often referred to as argumentum ad hominem. Today, the term ad hominem usually refers to a fallacy that attacks the arguer’s character rather than addressing their argument. However, the ad hominem Boethius and his successors described aligns closely with argumentum ex concessis and is not a fallacy. For clarity, this approach is best termed argumentum ex concessis, also known as argument from commitment.

In the 17th century, Galileo Galilei (d. 1642) used the term ad hominem to describe arguments that compel an opponent to accept an unwelcome conclusion based on premises they have accepted, even if the arguer does not endorse these premises personally (M. A. Finocchiaro, The Concept of Ad Hominem Argument in Galileo and Locke, 1974).

John Locke (d. 1704) also adopted this view, defining ad hominem as pressing someone with conclusions drawn from their own principles:

“Thirdly, A third Way, is to press a Man with Consequences drawn from his own Principles, or Concessions. This is already known under the name of Argumentum ad Hominem.” (John Locke, 1735, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, London: A. Betteswort, Vol. 2, p. 306)

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (d. 1716) furthered this concept, emphasising its value in revealing an opponent’s logical errors:

“The argument ad hominem has this effect, that it shows that one or the other assertion is false and that the opponent is deceived whatever way he takes it.” (G. W. Leibniz, 1765, New Essays Concerning Human Understanding, London: Macmillan, pp. 576-577)

This approach underscores the foundational principle of argumentum ex concessis – using the opponent’s own statements to reveal contradictions in their reasoning.

Isaac Watts (d. 1748) reinforced this concept, noting that argumentum ad hominem addresses the opponent’s stated beliefs rather than objective truth:

“When it [i.e. an argument] is built upon the profest [i.e., professed] Principles or Opinions of the Person with whom we argue, whether these Opinions be true or false, it is named Argumentum ad Hominem, an Address to our profest Principles.” (Isaac Watts, 1729, Logick: or, The Right Use of Reason in the Enquiry After Truth, London: Bible and Crown, p. 311)

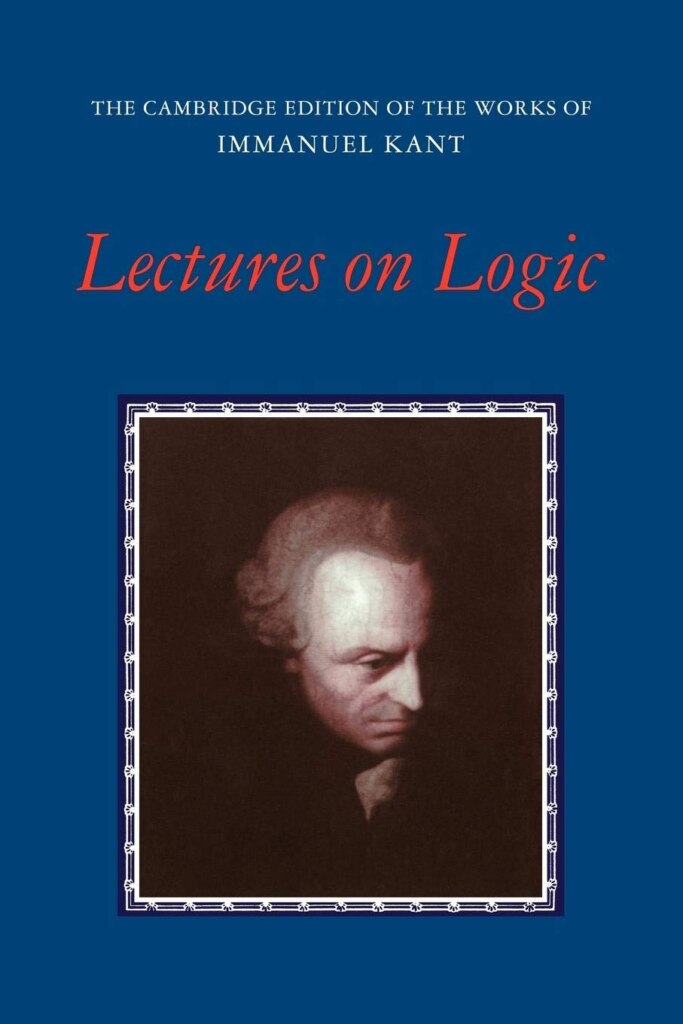

Immanuel Kant (d. 1804) also acknowledged the persuasive power of argumentum ex concessis, particularly its effectiveness in silencing an opponent:

“One can prove much apagogically ex concessis, namely, when the other has already conceded something. These are argumenta ad hominem. In mathematics there are many such proofs. They are always excellent.” (Immanuel Kant, 2009, Lectures on Logic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 483)

However, he cautioned that it does not necessarily lead to truth:

“An argumentum ad hominem is an argument that obviously is not true for everyone, but still serves to reduce someone to silence. E.g., when I get something ex concessis and from the particular propositions that someone else has. These are good means for getting someone off one’s back and for ending the dispute, but not for finding truth.” (Ibid., p. 241)

Arthur Schopenhauer (d. 1860) offered a clear distinction between argumentum ad rem (arguing to the matter) and argumentum ex concessis (arguing based on an opponent’s concessions):

“First of all, we must consider the essential nature of every dispute: what it is that really takes place in it. Our opponent has stated a thesis, or we ourselves, – it is all one. There are two modes of refuting it, and two courses that we may pursue.

“I. The modes are (1) ad rem, (2) ad hominem or ex concessis. That is to say: We may show either that the proposition is not in accordance with the nature of things, i.e., with absolute, objective truth; or that it is inconsistent with other statements or admissions of our opponent, i.e., with truth as it appears to him. The latter mode of arguing a question produces only a relative conviction, and makes no difference whatever to the objective truth of the matter.” (Arthur Schopenhauer, 1896, The Art of Controversy and Other Posthumous Papers, London: Swan Sonnenschein, p. 13)

This distinction highlights how argumentum ex concessis serves as a tool for relative conviction, contrasting with arguments based on objective truth.

These thinkers illustrate the enduring value of argumentum ex concessis across philosophical traditions, from mediaeval scholasticism to Enlightenment thought. Despite shifts in terminology – particularly the blending of argumentum ex concessis with argumentum ad hominem – this form of reasoning has remained a powerful tool in philosophical and theological discourse. By leveraging the opponent’s own commitments, this approach continues to facilitate rigorous debate, exposing inconsistencies and promoting a deeper pursuit of truth. This tradition of dialectical engagement aligns with similar techniques in other intellectual traditions, such as ilzam in Islamic thought, further demonstrating the effectiveness of argumentum ex concessis in fostering critical reflection.

III. Ilzam in the Islamic tradition

Understanding ilzam requires recognising its deep roots within Islamic intellectual history. The integration of Aristotelian philosophy during the 2nd/8th and 3rd/9th centuries significantly shaped Islamic thought, including the development of kalam. Key works such as Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Sophistical Refutations, and the Organon were meticulously rendered into Arabic, stimulating a wave of commentaries and expansions by Muslim intellectuals. This philosophical ferment coincided with, and significantly influenced, the development of Islamic theology (kalam).

However, Arabs and Muslims had long practised debate and intellectual exchange centuries before their formal encounter with Aristotelian dialectical works. Pre-Islamic Arab poets often composed satirical verses (al-hija’) or engaged in poetic battles known as an-naqa’id. Islamic scripture itself, the Quran, incorporates forms of dialectical disputation (mujadala), while Muslim legal and theological scholarship also featured traditions of dialectic (jadal) and disagreement literature (khilaf). These pre-Islamic and early Islamic traditions of argumentation coexisted alongside the newly imported Aristotelian methods.

By the late 3rd/9th century, Aristotelian logical works foundational to dialectic and disputation had been thoroughly studied and adapted by Islamic scholars. These developments, based on Aristotelian works, set the stage for philosophical theologians (mutakallimun) and jurists to engage deeply with both Greek thought and their native traditions of debate. However, to assert that the mutakallimun were merely influenced by Aristotle would be to overlook the complex and multifaceted nature of their intellectual heritage.

The Islamic corpus of argumentation was woven with innumerable and often untraceable threads. While some elements were undoubtedly Aristotelian, others emerged from Islamic and even pre-Islamic traditions. Some of these pre-Islamic elements may have even shaped Hellenic philosophy itself. Furthermore, certain Aristotelian influences were developed so extensively within Islamic thought that they evolved into unique and distinct strands. For instance, the practice of ilzam – strategically employing an opponent’s beliefs to reveal inconsistencies in their position – became a potent instrument in theological debate.

This convergence of native and foreign influences illustrates that while Aristotelian logic provided valuable tools, the Islamic tradition of debate was enriched by a multitude of diverse sources, including pre-Islamic Arab customs and early Islamic practices. The result was argumentation techniques that scholars, theologians, and jurists used to navigate and resolve complex intellectual disputes.

III. A. Defining ilzam

To understand the concept of ilzam within Islamic thought, it is essential to examine how it has been defined and understood by scholars throughout history. The term itself offers insights into its core meaning.

Ibn Faris (d. 395/1005), a renowned lexicographer of the Arabic language, explains in his Maqayis al-lugha:

اللام والزاء والميم أصل واحد صحيح، يدل على مصاحبة الشيء بالشيء دائما

“The letters lam, za’, and mim form a single, sound root that signifies the perpetual association of one thing with another.” (Ibn Faris, 1979, Mu‘jam maqayis al-lugha, ‘Abd as-Salam Muhammad Harun, ed. Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, Vol. 5, p. 245)

This etymological analysis emphasises the idea of continual association inherent in ilzam, indicating a binding connection and constant attachment between two entities. This insight is crucial for grasping the fundamental nature of ilzam as a persistent, inseparable link.

Murtada az-Zabidi (d. 1205/1790), an expert in lexicography, defined ilzam in his voluminous dictionary Taj al-‘arus as follows:

والإلزام: التبكيت

“ilzam means to silence [an opponent].” (Murtada az-Zabidi, 2000, Taj al-‘arus min jawahir al-Qamus, ed. Ibrahim at-Tarzi, Kuwait: Matbaʻat Hukumat al-Kuwayt, Vol. 33, p. 422)

This definition highlights that ilzam aims to bring the debate to a decisive conclusion where the opponent is left without a valid counter-argument.

Hans Wehr’s (d. 1981) dictionary provides the following definition for the expression alzamahu l-hujja:

“to force proof on s.o., force s.o. to accept an argument.” (Hans Wehr, 1994, A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, Urbana: Spoken Language Services, p. 1014)

This clarifies the purpose of ilzam: to compel an opponent in a disputation to accept the logical conclusions derived from their own stated beliefs or premises.

Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih Ira (d. 1332/1914), while elaborating upon its strategic function, explained that the goal of ilzam is not merely to expose an opponent’s weakness but to provide them with an opportunity for self-correction and deeper understanding. He states:

الزامی جواب اس لئے بھی اختیار کیا جاتا ہے کہ معترض اپنی مسلمہ و مالوفہ کتابوں سے اس قسم کے اشتباہ کو رفع کر لے۔

“Ilzami responses are also employed so that the objector may remove that sort of doubt from their own established and familiar books.” (Nuruddin, 1963, Fasl al-khitab li-muqaddama Ahl al-Kitab, Rabwah: Matba’ Diya’ al-Islam, p. 193)

This perspective highlights the potential of ilzam to facilitate intellectual growth and deeper engagement with one’s own beliefs. By compelling the opponent to confront the implications of their established sources, ilzam encourages a process of self-reflection and critical analysis.

Various scholars have articulated the purpose of ilzam and its characteristics, highlighting its distinct role in theological debate.

Imam al-Juwayni (d. 478/1085), a prominent Ash‘ari scholar and teacher of al-Ghazali, offers a concise definition in his Kafiya:

فأما الإلزام: فهو دفع كلام الخصم بما يوجب فصلا بينه وبين ما تضمن نصرته

“As for ilzam, it is the repudiation of the opponent’s argument by means of what imposes a severance between him and what comprises his support.” (al-Juwayni, 1979, al-Kafiya fi l-jadal, ed. Fawqiyya Husayn Mahmud, Cairo: Matbaʻat ʻIsa al-Babi al-Halabi, p. 70, §173)

This definition emphasises the strategic nature of ilzam, aiming to create a separation between the opponent and the very principles they claim to support.

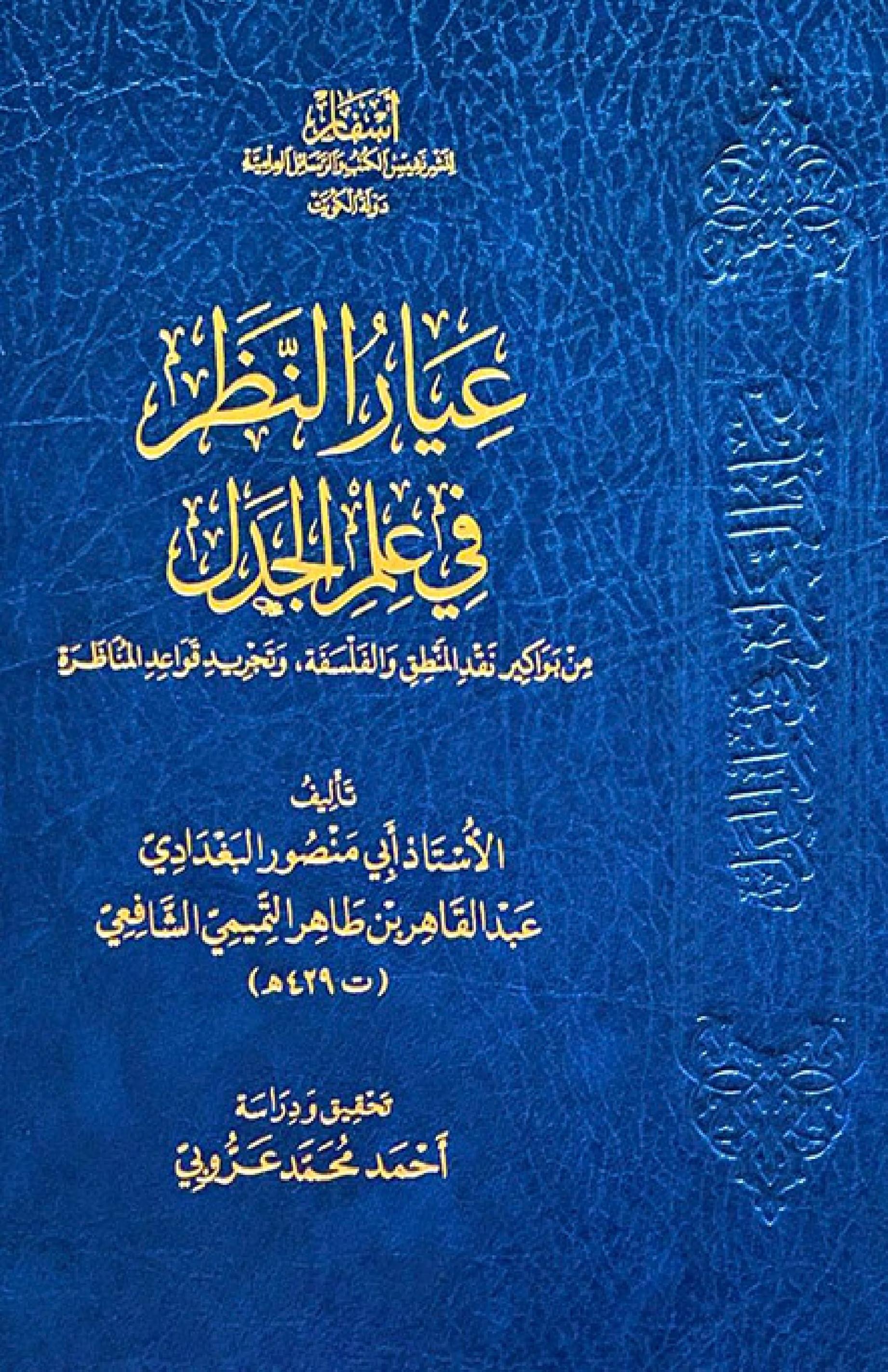

‘Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi (d. 429/1037), a leading Ash‘ari theologian and Shafi‘i jurist, provides a further definition in his ‘Iyar an-nazar. He writes:

أصل الإلزام: إظهار شهادة أصل لفرع، يريد السائل إلزام المسئول قوله فيه

“The rule of ilzam: To demonstrate evidence of a basis for a branch (far‘), where the questioner wants to compel the respondent to address it.” (‘Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi, 2020, ‘Iyar an-nazar fi ‘ilm al-jadal, ed. Ahmad Muhammad ‘Arrubi, Hawally: Asfar li-Nashr Nafis al-Kutub wa-r-Rasaʼil al-ʻIlmiyya, p. 467)

This definition emphasises the methodical nature of ilzam, highlighting how it involves revealing the basis for a claim and forcing the opponent to engage with it directly.

Ibn ‘Aqil (d. 513/1119), a distinguished Hanbali theologian and jurist from Baghdad, provides another perspective:

والإلزام: هو التعليق على الخصم ما لا يقول به بدلالة ما يقول به

“Ilzam: It is pinning onto the adversary what he does not profess, by showing him that it follows as a consequence of what he does profess.” (Ibn ‘Aqil, 1999, al-Wadih fi usul al-fiqh, ed. ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Abd al-Muhsin at-Turki, Beirut: Mu’assat ar-Risala, Vol. 1, p. 197)

This definition emphasises the aspect of compelling the opponent to accept unintended or undesirable consequences of their own beliefs.

In similar vein, ‘Ala’ ad-Din al-Mardawi (885/1480), a Hanbali scholar from Damascus, emphasises the strategic outcome of ilzam in theological debates:

[حقيقة] الإلزام […] إلجاء الخصم إلى الاعتراف بنقيض دليله إجمالا، حيث دل على نفي ما هو الحق عنده على صورة النزاع

“[The essence of] ilzam […] is forcing the opponent to acknowledge the contradiction of his evidence in general, where he indicates the negation of what he believes to be the truth in the form of the dispute.” (al-Mardawi, 2000, at-Tahbir sharh at-Tahrir fi usul al-fiqh, ed. ʻAbd ar-Rahṃan ibn ʻAbd Allah al-Jibrin, Riyadh: Maktabat ar-Rushd, Vol. 2, p. 736)

This definition illuminates the tactical dimension of ilzam, highlighting how it functions not merely to expose inconsistencies, but to compel the opponent to recognise that their own argumentation undermines their position.

Adding to this, the Quranic scholar and Egyptian Shafi‘i jurist Badr ad-Din az-Zarkashi (d. 794/1392) emphasises the conclusive nature of ilzam in forcing the opponent to concede:

والالزام عبارة عن انتهاء دليل المستدل إلى مقدمات ضرورية أو يقيني مشهور، يلزم المعترض الاعتراف به ولا يمكنه جحده فينقطع بذلك

“And ilzam is an expression referring to the arguer’s evidence ending at necessary premises or a well-known certainty that the objector is bound to acknowledge and cannot deny, so he is cut off by that.” (az-Zarkashi, 1998, Tashnif al-masamiʻ bi-Jamʻ al-jawamiʻ, ed. Sayyid ʻAbd al-ʻAziz; ʻAbd Allah Rabiʻ, Cairo: Maktab Qurtuba li-l-Bahth wa-l-ʻIlmi wa-Ihyaʼ at-Turath al-Islami, Vol. 3, p. 400)

Moving beyond general definitions, as-Sayyid ash-Sharif al-Jurjani (d. 816/1413), a leading Ash‘ari theologian, logician and philosopher from Samarqand, in his at-Ta‘rifat provides a concise definition that highlights the role of the opponent’s premises:

الدليل الإلزامي: ما سلم عند الخصم، سواء كان مستدلا عند الخصم أو لا

“Argument from commitment (ad-dalil al-ilzami): That which is among the accepted premises of the opponent, whether it is a proffered position of the opponent or not.” (ash-Sharif al-Jurjani, 1983, Kitab at-Ta‘rifat, Dar al-Kutub al-ʻIlmiyya, p. 104)

Similarly, Muhammad ‘Ali Thanvi (d. 1191/1777), an erudite Hanafi lexicologist from India, states in Kashshaf istilahat al-funun, his encyclopaedia of technical terms which he completed 1158/1745, under the entry for hujja:

والحجة الإلزامية هي المركبة من المقدمات المسلمة عند الخصم المقصود منها إلزام الخصم وإسكاته

“The argument from commitment (al-hujja al-ilzamiyya) is composed of premises accepted by the opponent, and its purpose is to obligate the opponent and silence him.” (Muhammad ‘Ali Thanvi, 1853, Kashshaf istilahat al-funun, ed. Muhammad Wajih; ‘Abd al-Haqq; Ghulam Qadir, Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 2, p. 284)

The Gujarati scholar ‘Abd an-Nabi Ahmadnagari, in his well-known 12th/18th-century encyclopaedic work Dustur al-‘ulama’, further clarifies this:

الجواب الإلزامي: هو الجواب بما هو مسلم عند الخصم وإن كان فاسدا في نفس الأمر

“Dialectical response (al-jawab al-ilzami): A response based on what is accepted by the opponent, even if it is actually incorrect.” (‘Abd an-Nabi Ahmadnagari, 1911, Jamiʻ al-ʻulum: al-mulaqqab bi-Dastur al-ʻulamaʼ fi isṭilahat al-ʻulum wa-l-funun, Hyderabad: Matbaʻat Daʼirat al-Maʻarif an-Nizamiyya, Vol. 1, p. 420)

These definitions emphasise that ilzam is not about imposing external truths but about using the opponent’s own accepted beliefs to expose inconsistencies or lead them to conclusions they find problematic. Indeed, ilzam relies on the opponent’s own accepted beliefs, even if those beliefs might be flawed. This highlights the subjective nature of ilzam in contrast to demonstrative reasoning, which seeks to establish objective truths.

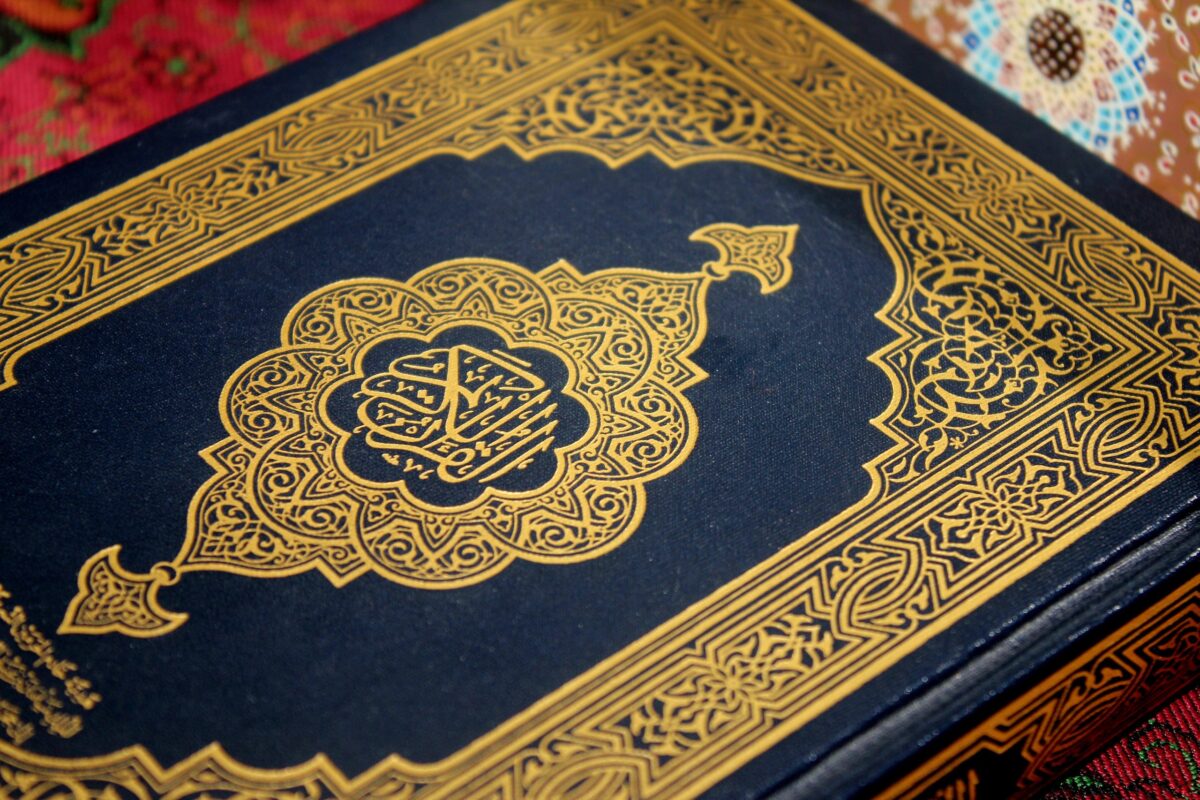

Having established the definition and scholarly understanding of ilzam, it is crucial to examine its presence within the foundational text of Islam, the Holy Quran. As the primary source of Islamic teachings, the Quran’s utilisation of ilzam demonstrates the method’s inherent legitimacy within the Islamic intellectual tradition. This section will explore specific examples of ilzam in the Quran, analysing how this technique is employed to address various theological and philosophical issues.

III. B. Ilzam in the Quran and Sunnah

The Quran, while primarily focused on conveying divine truths and guidance, frequently engages in discourse with those who oppose or question its teachings. In these instances, the Quran employs various argumentative strategies, including ilzam, to address challenges and to expose the inconsistencies inherent in opposing viewpoints.

III. B. 1. The Quran’s use of ilzam

The Quran’s use of ilzam often takes the form of presenting hypothetical scenarios or posing rhetorical questions that lead the reader to recognise the absurdity or contradiction inherent in a particular belief or claim.

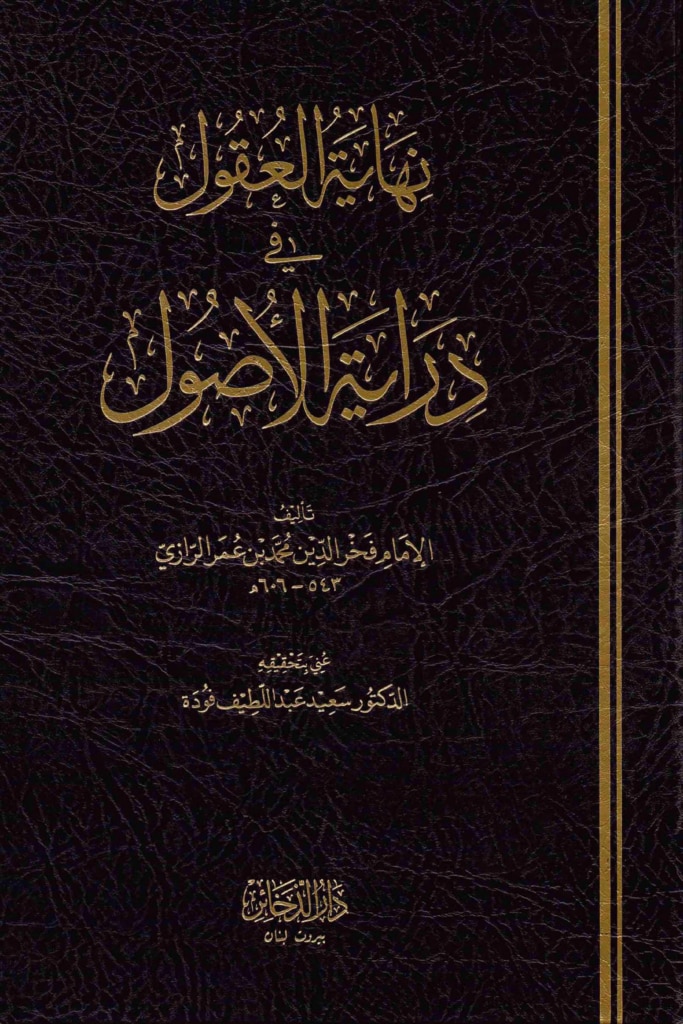

Fakhr ad-Din ar-Razi (d. 606/1210) states in his at-Tafsir al-kabir that the Quran employs various methods to establish the truth of Islam, including dialectical (ilzami) proofs:

اعلم أنا قد بينا أن الله تعالى استدل على صحة دين محمد ﷺ بوجوه، بعضها إلزامية، وهو أن هذا الدين دين إبراهيم فوجب قبوله، وهو المراد بقوله: وَمَنۡ يَّرۡغَبُ عَنۡ مِّلَّةَ اِبۡرٰهٖمَ اِلَّا مَنۡ سَفِهَ نَفۡسَهٗ

“Know that we have already clarified that Allah the Exalted has established proof of the truth of Muhammad’ssa religion in multiple ways. Some of these proofs are dialectical (ilzamiyya), such as stating that this religion is the religion of Abraham, and thus it must be accepted. This is what is meant by the verse: ‘And who will turn away from the religion of Abraham but he who makes a fool of himself?’ (Surah al-Baqarah, 2:131)” (Fakhr ad-Din ar-Razi, 1999, at-Tafsir al-kabir, Beirut: Ihya’ at-Turath al-‘Arabi, Vol. 4, p. 122)

Ar-Razi further highlights the Quran’s use of dialectic (jadal), which he considers one of the three methods of engaging with others, as mentioned in the Quran:

اُدۡعُ اِلٰی سَبِیۡلِ رَبِّکَ بِالۡحِکۡمَۃِ وَالۡمَوۡعِظَۃِ الۡحَسَنَۃِ وَجَادِلۡہُمۡ بِالَّتِیۡ ہِیَ اَحۡسَنُ

“Call unto the way of thy Lord with wisdom and goodly exhortation and argue with them in a way that is best.” (Surah an-Nahl, 16:125)

Alongside wisdom (hikma) and goodly exhortation (maw‘iza hasana), jadal aims to compel the opponent (ilzam) using premises they already accept. The goal is to expose contradictions in the opponent’s position, forcing them to confront the logical consequences of their own beliefs.

Ar-Razi states that:

واعلم أن الدعوة إلى المذهب والمقالة لا بد وأن تكون مبنية على حجة وبينة، والمقصود من ذكر الحجة، إما تقرير ذلك المذهب وذلك الاعتقاد في قلوب المستمعين، وإما أن يكون المقصود إلزام الخصم وإفحامه

“Know that inviting to a doctrine or belief must necessarily be based on evidence and proof, and the purpose of presenting such evidence is either to establish that doctrine and belief in the hearts of the listeners, or the aim is to compel the opponent (ilzam al-khasm) and silence him.” (Ibid., Vol. 20, p. 286)

In his discussion of jadal, ar-Razi highlights the ideal form of this method:

أن يكون دليلاً مركباً من مقدمات مسلمة في المشهور عند الجمهور، أو من مقدمات مسلمة عند ذلك القائل، وهذا الجدل هو الجدل الواقع على الوجه الأحسن

“[T]hat the argument is composed of premises that are accepted either by the public or at least by the opponent. This form of debate is the one that occurs in the best manner.” (Ibid., Vol. 20, p. 287)

This method of jadal, which is the best form, uses the opponent’s own accepted premises to challenge them. Ar-Razi notes that this is the type of argumentation referred to in the Quranic command: “and argue with them in a way that is best” (wa-jadilhum bi-llati hiya ahsan). By emphasising ilzam, ar-Razi shows that the most effective form of jadal is one that compels the opponent by using their own beliefs, leading them to acknowledge the logical consequences of their position. This method aligns with both logical consistency and ethical argumentation.

The Quran’s use of ilzam often takes the form of presenting hypothetical scenarios or posing rhetorical questions that lead the reader to recognise the absurdity or contradiction inherent in a particular belief or claim. For instance, in challenging polytheistic beliefs, the Quran utilises ilzam to demonstrate the logical impossibility of multiple gods:

قُلۡ لَّوۡ کَانَ مَعَہٗۤ اٰلِـہَۃٌ کَمَا یَقُوۡلُوۡنَ اِذًا لَّابۡتَغَوۡا اِلٰی ذِی الۡعَرۡشِ سَبِیۡلًا

“Say, ‘Had there been other gods with Him as they allege, then certainly (by their help the idolaters) would have sought out a way to the Owner of the Throne.’” (Surah al-Isra’, Ch.17: V.43)

This verse employs ilzam by positing a hypothetical scenario: if there were truly multiple gods, as polytheists claim, then those gods would inevitably seek to usurp each other’s power and authority. This scenario, however, contradicts the observed order and harmony within the universe, implicitly demonstrating the falsehood of polytheism.

Another example is found in Surah al-Mu’minun, where the Quran challenges the notion of associating partners with Allah:

مَا اتَّخَذَ اللّٰہُ مِنۡ وَّلَدٍ وَّمَا کَانَ مَعَہٗ مِنۡ اِلٰہٍ اِذًا لَّذَہَبَ کُلُّ اِلٰہٍۭ بِمَا خَلَقَ وَلَعَلَا بَعۡضُہُمۡ عَلٰی بَعۡضٍ ؕ سُبۡحٰنَ اللّٰہِ عَمَّا یَصِفُوۡنَ

“Allah has not taken unto Himself any son, nor is there any other god along with Him; in that case each god would have taken away what he had created, and some of them would, surely, have sought domination over others. Glorified be Allah (far) above that which they allege.” (Surah al-Mu’minun, Ch.23: V.92)

Here, the Quran uses ilzam to show that if there were multiple gods, each would claim ownership and control over their creations, leading to conflict and chaos. This again contradicts the observed order and unity within creation, pointing towards the logical conclusion of a single, supreme God.

The Quran also utilises ilzam to address those who deny the possibility of divine revelation. In Surah al-An‘am, for example, it responds to the claim that God has not revealed anything to humankind:

اِذۡ قَالُوۡا مَاۤ اَنۡزَلَ اللّٰہُ عَلٰی بَشَرٍ مِّنۡ شَیۡءٍ ؕ قُلۡ مَنۡ اَنۡزَلَ الۡکِتٰبَ الَّذِیۡ جَآءَ بِہٖ مُوۡسٰی

“[W]hen they say, ‘Allah has not revealed anything to any man.’ Say, ‘Who revealed the Book which Moses brought?’” (Surah al-An‘am, Ch.6: V.92)

This verse employs ilzam by challenging the objector to explain the origin of previous scriptures, such as the Torah revealed to Mosesas. If they acknowledge the divine origin of those scriptures, then their claim that God does not reveal anything to humans becomes self-contradictory.

This method of ilzam within the Quran encourages critical thinking and reflection. By presenting hypothetical scenarios or posing pointed questions, it compels the reader to confront the logical consequences of their beliefs and to recognize the inconsistencies inherent in those who oppose the Quran’s message.

Imam Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (d. 333/944), the eponymous founder of the Maturidi school of Islamic theology, recognises the Quran’s use of ilzam:

وطريقة إلزام الخصم نأخذها من القرآن الكريم، فحينما جاء الحبر السمين وقال للنبي ﷺ: ﴿ما أنزل الله على بشر من شيء﴾ يريد بذلك إنكار نبوة محمد، فرد القرآن عليه: ﴿قل من أنزل الكتاب الذي جاء به موسى﴾ وهذا إلزام أقر به الخصم

“The method of compelling the opponent (ilzam al-khasm) is taken from the Quran itself. For example, when the stout rabbi came to the Prophetsa and said, ‘Allah has not revealed anything to any man,’ in an attempt to deny the prophethood of Muhammadsa, the Quran responded by saying, Say, ‘Who revealed the Book which Moses brought?’, which was a form of ilzam that the opponent had to acknowledge.” (al-Maturidi, 2005, Ta’wilat Ahl as-sunna, ed. Majdi Basallum, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, Vol. 1, p. 148)

Al-Qurtubi also illustrates the use of ilzam in the Quran in his exegesis. In the commentary on the story of Abrahamas breaking the idols in Surah al-Anbiya’, al-Qurtubi highlights how Abraham’sas statement about the largest idol may force his opponents to confront the inconsistency of their beliefs:

وقيل: أي لم ينكرون أن يكون فعله كبيرهم؟ فهذا إلزام بلفظ الخبر. أي من اعتقد عبادتها يلزمه أن يثبت لها فعلا، والمعنى: بل فعله كبيرهم فيما يلزمكم.

“It is said: did they not deny that the largest of them could have done it? This is an ilzam that is expressed in the form of a declarative statement. Whoever believes in their worship is bound (yalzamuhu) to attribute action to them. The meaning is: ‘Rather, their largest one did it, according to what you are bound to accept (yalzamukum).’” (al-Qurtubi, 1967, al-Jami‘ li-ahkam al-Quran, ed. Abu Ishaq Ibrahim Atfish, Cairo: Dar al-Kutub al-Misriyya, Vol. 11, p. 300)

Al-Qurtubi’s explanation shows how Abraham’sas statement forces his audience to confront the absurdity of their beliefs by compelling them to acknowledge the logical consequences of idol worship.

III. B. 2. The Promised Messiah’sas perspective on Quranic ilzam

The Promised Messiahas, in his writings, also refers to the Quran’s use of ilzam to counter those who rejected its message. He states:

چنانچہ اوّل ان کے اسکات و الزام کے لیے ہر ایک قسم کے نشان قرآن شریف نے پیش کئے، مگر انہوں نے اپنے تعصب کی وجہ سے ان دلائل کو قبول نہ کیا۔ آخر جب انہوں نے کسی دلیل کو قبول نہ کیا۔ اور کسی نشان پر ایمان نہ لائے۔ تو اتمام حجت کی غرض سے مباہلہ کے لیے ان سے درخواست کی گئی۔

“Therefore, initially, the Holy Quran presented all kinds of signs to render them [the Christians] silent (iskat) and refute (ilzam) them. However, due to their prejudice, they did not accept these arguments. Finally, when they refused to accept any proof or believe in any sign, they were invited to a prayer duel (mubahala) for the purpose of conclusive argumentation (itmam-e ḥujjat).” (Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, 2019, Majmu‘a-e ishtiharat, Qadian: Nazarat-e Nashr-o-Isha‘at, Vol. 1, p. 232)

As an illustration of the Quran’s use of ilzam, the Promised Messiahas provides the following example in the context of addressing the Christian belief in Jesusas as the son of God:

جواب دو قسم کے ہوتے ہیں۔ ایک تحقیقی، دوسرے الزامی۔ اﷲ تعالیٰ نے بھی بعض جگہ الزامی جوابوں سے کام لیا ہے۔ اس میں معترض کو اپنے مذہب کی کمزوری معلوم ہوتی ہے۔ چنانچہ جب عیسائیوں نے کہا کہ عیسٰی خدا کا بیٹا ہے اور دلیل یہ کہ مریم کنواری کے پیٹ سے پیدا ہوا تو ﷲ تعالیٰ نے فرمایا۔ اِنَّ مَثَلَ عِیۡسٰی عِنۡدَ اللّٰہِ کَمَثَلِ اٰدَم یعنی اگر یہی اس کا بیٹا ہونے کا ثبوت ہے تو آدم بطریق اوّل بیٹا ہونا چاہئیے۔

“Replies are of two types. One by way of tahqiq and the other by way of ilzam. Allah the Exalted has also made use of ilzami replies in certain instances. These inform the critic of the weakness of his own religious worldview. Thus, when the Christians claimed that Jesus is the Son of God and its proof is that he was born of the Virgin Mary, Allah the Exalted replied by saying:

اِنَّ مَثَلَ عِیۡسٰی عِنۡدَ اللّٰہِ کَمَثَلِ اٰدَم

Meaning that if this indeed was the proof of him being the Son [of God] then Adam has the first right to be the Son [of God]. (Surah Al ‘Imran, Ch.3: V.60)” (Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, 2022, Malfuzat [Urdu], Farnham: Islam International Publications Ltd., Vol. 10, p. 316)

Here, the Promised Messiahas highlights how the Quran uses ilzam to point out the flawed logic in the Christian claim. If virgin birth were sufficient proof of divine sonship, then Adam would have an even stronger claim to that title.

The Quran, as exemplified by these examples, utilises a variety of argumentative strategies in its engagement with both polytheistic beliefs and the doctrines of the People of the Book. While ilzam is employed to expose inconsistencies and prompt reflection, other approaches, such as providing direct evidence and appealing to reason and observation, are also used.

III. C. The mechanics of ilzam

Having seen ilzam employed within the Quran itself, it is now helpful to examine in greater detail the mechanics of this argumentative technique – how it functions to achieve its intended purpose. Ilzam centres around the principle that every proposition carries inherent consequences. This involves confronting an opponent with the logical implications of their own statements, even if these consequences are not immediately apparent or explicitly stated. Through ilzam, inconsistencies or contradictions emerging from a flawed premise are brought to light, often revealing the weakness of the original position.

In practice, ilzam presents the opponent with a dilemma: either accept the problematic implications of their view, or abandon their initial position. Since individuals are often unaware of these logical consequences until explicitly exposed through ilzam, it becomes a powerful tool for challenging deeply held but poorly examined beliefs.

This approach resonates with Imam al-Ghazali’s (d. 505/1111) discussion of logical consequence (lazim) and its premise (malzum) in al-Mustasfa:

فإن كل إثبات له لوازم، فإنتفاء اللازم يدل على إنتفاء الملزوم

“Every affirmation has consequents (lawazim), and the negation of the consequent (lazim) indicates the negation of the antecedent (malzum).” (al-Ghazali, 1993, al-Mustasfa, ed. Muhammad ‘Abd as-Salam ‘Abd ash-Shafi, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, p. 163)

Al-Ghazali highlights that demonstrating the falsehood or absurdity of a proposition’s consequences directly undermines the validity of the original proposition itself. This is precisely the mechanism employed in ilzam, where, by demonstrating the untenable consequences of an opponent’s claim, the flaws in their reasoning are revealed. This reflects the logical principle known as modus tollens, which states that if a conditional statement (“if P, then Q”) is true, and the consequent (Q) is false, then the antecedent (P) must also be false.

The process of ilzam typically unfolds as follows: the obligating party (mulzim) begins by presenting a premise (malzum) already accepted by the opponent. Building on this accepted premise, the mulzim constructs a logical argument leading to a conclusion (lazim) that the opponent cannot readily dispute. The strength of ilzam lies in its logical rigour: once the opponent accepts the initial premise, they are compelled to accept its logical implications, even if it contradicts their broader stance.

For an argument to qualify as ilzam, three conditions must be met:

- The premise must be accepted by the opponent.

- The opponent must not dispute the conclusion drawn from the premise.

- There must be a clear and necessary logical connection between premise and conclusion. A demonstrable disconnect invalidates the ilzam.

The logical structure of ilzam often involves a disjunctive syllogism (qisma or taqsim), systematically eliminating propositions to affirm a sole remaining possibility. This relies on basic inference (istidlal) from immediate data acting as an indicator (dalil). The indicator’s validity rests on a causal relationship (‘illa) between it and the signified object. Once this causal link’s relevance is established, the argument is deemed valid.

Ilzam functions by using the opponent’s own beliefs against them, making the arguer’s personal stance irrelevant. The antecedent is granted and the consequent is affirmed, solely to demonstrate the problematic implications of the opponent’s view. This has been a key technique in Islamic theology, allowing scholars to refute doctrines without personally endorsing the counterarguments.

‘Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi categorises ilzam into six forms, each with a different method of logical implication:

- Causality (al-‘illa): The accepted principle necessitates a specific, and perhaps problematic, effect.

- Opposition (al-mu‘arada): Exposing contradictions between the opponent’s accepted ideas.

- Indication (ad-dalala): Using accepted evidence to compel acceptance of a related conclusion.

- Division (at-taqsim): Showing how every logical possibility of an opponent’s argument leads to an unacceptable outcome.

- General Meaning (i‘ta’ al-ma‘na fi l-jumla): Applying the broader implications of the opponent’s argument consistently to demonstrate unintended consequences.

- Rational Implication (iqtida’ al-‘aql): Using pure logic to compel the opponent to accept a conclusion necessitated by their premises, without external evidence. (‘Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi, ibid., pp. 469-471)

III. D. The strategic nature of ilzam: Dissociating argument from belief

While ilzam relies on logical deductions from an opponent’s accepted premises, it is crucial to understand that employing this method does not necessitate personal belief in those premises or the resulting conclusions. It can function as a strategic tool to highlight the inherent weaknesses or inconsistencies within an opposing viewpoint, even if the arguer does not subscribe to the specific premises used in the process. Indeed, scholars throughout Islamic history have recognised this strategic nature of ilzam, distinguishing between its function as a tool of refutation and the arguer’s own theological convictions.

In the concept of the dialectical strategy of ilzam, the debater may utilise arguments to expose the logical inconsistencies of their opponent’s position, even if they do not personally subscribe to the premises of those arguments. This technique prioritises demonstrating the absurdity or incoherence of the opponent’s stance, compelling them to reconsider.

Al-Ghazali, in his influential work Tahafut al-falasifa (The Incoherence of the Philosophers), articulated this approach:

فأبطل عليهم ما اعتقدوه مقطوعا، بإلزامات مختلفة؛ فألزمهم تارة مذهب المعتزلة، وأخرى مذهب الكرامية، وطورا مذهب الواقفية

“I will render murky what they believe in [by showing] conclusively that they must hold to various consequences (ilzamat) [of their theories]. Thus, I hold them to the [full and undesirable] consequences of their doctrine (ulzimuhum) by arguing at times from the position of the Mu‘tazila, at times from the position of the Karramiyya, and at other times from the position of the Waqifiyya.” (al-Ghazali, 1966, Tahafut al-falasifa, ed. Sulayman Dunya, Cairo: Dar al-Ma‘arif, p. 82)

al-Ghazali later elaborated on this approach in his al-Iqtisad fī l-i‘tiqad, explicitly stating that some of the positions he adopted in Tahafut al-falasifa did not represent his actual doctrines. They were only assumed for the sake of argument: he wanted to show that the philosophers’ premises did not lead to their conclusions. Referring to an instance in which he used ilzam, he states:

وقد أطنبنا في هذه المسألة في كتاب التهافت، وسلكنا في إبطال مذهبهم تقرير بقاء النفس التي هي غير متحيز عندهم وتقدير عود تدبيرها إلى البدن سواء كان ذلك البدن هو عين جسم الانسان أو غيره، وذلك إلزام لا يوافق ما نعتقده؛ فإن ذلك الكتاب مصنف لابطال مذهبهم لا لاثبات المذهب الحق، ولكنهم لما قدروا أن الانسان هو ما هو باعتبار نفسه وأن اشتغاله بتدبير كالعارض له والبدن آلة لهم، ألزمناهم بعد اعتقادهم بقاء النفس وجوب التصديق بالاعادة وذلك برجوع النفس إلى تدبير بدن من الأبدان

“We have discussed this matter with elaboration in the book at-Tahafut, and based our refutation of their doctrine on positing the persistence of the soul, which for them is not extended, and positing its return to govern a body, whether this body is the exact same body of the man or another body. This is an ilzam that is not in accordance with what we believe; for that book was composed to refute their doctrines, not to establish the true doctrines (madhhab al-haqq). Given that they assumed that man is what he is by virtue of his soul and that his occupation with governing a body is accidental to him, and since, according to them, the body is an instrument, we made an ilzam on them – since they believe in the persistence of the soul – to affirm the reality of re-creation as the return of the soul to its governing a body – any body.” (al-Ghazali, 2004, al-Iqtisad fi l-i‘tiqad, ed. ‘Abd Allah Muhammad al-Khalili, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, p. 117)

Al-Ghazali’s explanation clarifies that his goal in the Tahafut was to demonstrate the limitations of the philosophers’ arguments, not to endorse the alternative positions he employed through ilzam. This highlights the strategic nature of ilzam: it allows for the deconstruction of an opponent’s argument without requiring the debater to subscribe to the specific premises used in the refutation.

Sayf ad-Din al-Amidi (d. 631/1233), a major Ash‘ari theologian, rationalist philosopher and Shafi‘i jurist, in his Abkar al-afkar, echoes this sentiment:

قلنا: ما يذكر بطريق الإلزام لا يلزم أن يكون معتقدا للملزم

“We said: What is mentioned by way of ilzam is not necessarily something the one employing it (al-mulzim) believes in.” (al-Amidi, 2004, Abkar al-afkar fi usul ad-din, ed. Ahmad Muhammad Mahdi, Cairo: Matbaʻat Dar al-Kutub wa-l-Wathaʼiq al-Qawmiyya, Vol. 1, p. 507)

This statement explicitly states that the one using ilzam may not personally subscribe to the premises or conclusions employed. The focus is on demonstrating the logical consequences of the opponent’s position, not on advocating for the arguer’s own beliefs.

Therefore, employing ilzam does not necessitate belief in its premises. Agreement with an opponent’s claims for the sake of argument does not equate to endorsing those claims as truth. This distinction is important for understanding the legitimacy of ilzam and for deflecting accusations of hypocrisy or insincerity.

Ibn Hazm (d. 456/1064), the Cordoban polymath, in al-Taqrib li-hadd al-mantiq, exemplifies this point by addressing a common accusation levelled against Muslims:

وكثيرا ما يحتج علينا اليهود بأننا قد وافقناهم على أن دينهم قد كان حقا ونبيهم حق ويريدون من ها هنا إلزامنا الإقرار به حتى الآن فاضبط هذا المكان واعلم أنا إنما وافقناهم على مقدماتهم

“Often the Jews argue against us that we have agreed with them that their religion was true and their prophet was true, and from this, they want to compel us to acknowledge it even now. So grasp this point and know that we have only agreed with them on their premises.” (Ibn Hazm, 1983, Rasa’il Ibn Hazm, ed. Ihsan ‘Abbas, Beirut: al-Muʼassasa al-ʻArabiyya li-d-Dirasat wa-n-Nashr, Vol. 4, p. 269)

This passage illustrates that agreement on premises for the sake of argument does not necessarily imply endorsement of the opponent’s position.

In conclusion, ilzam, when employed strategically, allows for the exposure of flaws in an opposing argument without requiring the arguer to personally endorse the premises or conclusions utilised.

III. D. Distinguishing dialectic from demonstration

Understanding the relationship between ilzam and other forms of argumentation, particularly demonstrative proof, i.e., burhan or tahqiq, is crucial for a comprehensive appreciation of ilzam‘s role in Islamic theological discourse. This section will explore how classical Islamic scholars and the Promised Messiahas distinguished between these methods, highlighting their distinct characteristics, objectives, and applications.

Ilzam operates as a subjective or relative argument. It is relative because it depends on principles that are not necessarily universally true but are accepted by the opponent. The arguer uses these principles to force the opponent into a logical impasse, exposing contradictions within their beliefs. This often involves demonstrating the problematic consequences that arise from the opponent’s position.

In contrast, burhan or tahqiq is an objective or absolute form of argumentation (argumentum ad veritatem), grounded in universally accepted principles. It seeks to establish truths independent of any opponent’s views. This approach is employed when the goal is to demonstrate a universally valid truth rather than simply refuting an opponent’s position.

This distinction between demonstrative and dialectical argumentation has deep roots in the philosophical tradition that influenced Islamic thought. Aristotle provides a clear articulation of this distinction:

“Now a deduction is an argument in which, certain things being laid down something other than these necessarily comes about through them. It is a demonstration, when the premisses from which the deduction starts are true and primitive, or are such that our knowledge of them has originally come through premisses which are primitive and true; and it is a dialectical deduction, if it reasons from reputable opinions.” (Aristotle, Topics, 100a25–26).

This Aristotelian framework, distinguishing between arguments based on true and primitive premises versus those based on reputable opinions, provided a philosophical foundation that Islamic scholars would build upon and adapt to their theological discussions.

III. D. 1. Classical Islamic perspectives

Classical Islamic scholars recognised the distinction between ilzam and burhan, employing both methods strategically within their theological discourse.

Ibn Sina (d. 428/1037), a towering figure in Islamic philosophy, provides valuable insights into these distinct forms of argumentation. He discusses how dialectic (jadal) and burhan function within the broader context of debate or disputation (munazara). He explains that every syllogistic address (khitab qiyasi) aims at tasdiq, i.e., credibility, belief, or acceptance, and those syllogistic addresses which aim at tasdiq either intend to clarify truth (al-idah li-l-haqq) – which can be achieved through demonstration (burhan) and instruction (ta‘lim) – or intend victory (ghalaba) and forcing conclusions (ilzam):

والتي القصد فيها التصديق فإما أن يكون المراد فيها الإيضاح للحق، وهو البرهان والتعليم؛ وإما أن يكون الراد فيها الغلبة والإلزام

“And those [syllogistic addresses] that aim at credibility (tasdiq) either intend to uncover the truth (al-idah li-l-haqq), which is demonstration (burhan) and instruction (ta‘lim), or intend victory (ghalaba) and forcing conclusions (ilzam).” (Ibn Sina, 1965, Kitab ash-Shifa’, al-Mantiq, al-Jadal, ed. Ahmad Fu’ad al-Ahwani, Cairo: al-Matba‘a al-Amiriyya, p. 18)

This categorisation of syllogistic addresses reveals a crucial aspect of ilzam: its potential to be employed for achieving victory in a debate, rather than solely for clarifying truth. This emphasis on prevailing over the opponent, through compelling them to accept a position, aligns ilzam with the broader category of jadal, as Ibn Sina further clarifies:

واسم المناظرة مشتق من النظر، والنظر لا يدل على غلبة أو معاندة بوجه. وأما الجدل فإنه يدل على تسلط بقوة الحطاب في الإلزام

“The word munazara is derived from nazar, and nazar signifies neither victory (ghalaba) nor contention (mu‘anada). But jadal signifies prevailing through speech in forcing one’s opponent to accept one’s position (ilzam)”. (Ibid., p. 20)

This explanation highlights the forceful and persuasive nature of jadal, as it involves compelling the opponent to accept a position. This emphasis on prevailing over the opponent through ilzam distinguishes jadal from the approach of munazara.

This understanding of the limitations of jadal contrasts with the definitive nature of burhan. Avicenna, for instance, succinctly articulates this point:

لا يفيد اليقين إلا البرهان

“Nothing yields certainty except burhan.” (Ibid., p. 11)

This statement emphasises that burhan possesses a unique epistemic quality: it alone can produce certainty (yaqin) regarding the truth of a proposition. While jadal, including the technique of ilzam, may effectively compel or silence an opponent, it does not necessarily lead to the same level of epistemic certainty that burhan aims to achieve.

Al-Ghazali offers a concise distinction between demonstrative and dialectical arguments in his Mustasfa based on the nature of their premises:

فإن كانت المقدمات قطعية سميناها برهانا، وإن كانت مسلمة سميناها قياسا جدليا

“If the premises are definitive (qat‘iyya), we call it demonstration (burhan), and if the premises are [merely] accepted (musallama), we call it dialectical syllogism (qiyas jadali).” (al-Ghazali, al-Mustasfa, ibid., p. 31)

This statement clearly delineates the epistemological distinction between burhan and dialectical arguments like ilzam. For al-Ghazali, the key difference lies in the nature of the premises used: burhan relies on premises that are definitively true (qat‘iyya), while dialectical arguments use premises that are simply accepted (musallama) by the opponent, regardless of their objective truth value. This aligns with the broader classical understanding that burhan aims at establishing truth, while dialectical methods like ilzam aim at victory in debate through the opponent’s own concessions.

‘Abd an-Nabi Ahmadnagari offers a more concise distinction between demonstrative and dialectical arguments:

ثم اعلم أن الدليل تحقيقي وإلزامي. (والدليل التحقيقي) ما يكون في نفس الأمر ومسلما عند الخصمين. (والدليل الإلزامي) ما ليس كذلك فيقال هذا عندكم لا عندي

“Furthermore, an argument (dalil) can be either demonstrative (tahqiqi) or dialectical (ilzami). The tahqiqi dalil is what is true in reality and accepted by both disputants. The ilzami dalil is not so, and it is said, ‘This is valid according to you, not according to me.’” (‘Abd an-Nabi Ahmadnagari, ibid., Vol. 2, pp. 108-109)

Ibn Wahb al-Katib (d. 335/947) elaborates on this distinction in his Burhan, contrasting the aims of bahth (research) and jadal (dialectic), which correlate with burhan and ilzam, respectively:

وحق الجدل أن تبنى مقدماته بما يوافق الخصم عليه، وإن لم يكن نهاية الظهور للعقل، وليس هذا سبيل البحث، لأن حق الباحث أن يبني مقدماته بما هو أظهر الأشياء في نفسه، وأثبتها لعقله، لأن يطلب البرهان ويقصد لغاية التبيين والبيان، وألا يلتفت على إقرار مخالفه. فأما المجادل فلما كان قصد، إنما هو إلزام خصمه الحجة، كان أوكد الأشياء أن يلزمه إياها من قوله

“The proper approach to dialectic (jadal) is to construct its premises based on what the opponent agrees with, even if it is not the most self-evident to reason. This differs from the method of research (bahth), as a researcher (bahith) should base their premises on what is most apparent to themselves and most firmly established in their own mind. The researcher seeks demonstrative proof (burhan) and aims for ultimate clarity and explanation, without concern for their opponent’s acknowledgment. As for the debater (mujadil), since their intention is only to force conclusions (ilzam) upon their opponent with proof (hujja), the most effective approach is to force conclusions (ilzam) upon them using their own words.” (Ibn Wahb al-Katib, 1969, al-Burhan fi wujuh al-bayan, ed. Hifni Muhammad Sharaf, Cairo: Maktabat ash-Shabab, p. 179)

‘Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi further elucidates the roles of burhan and ilzam within kalam:

أصل الآلات في علم الكلام شيئان، هما: البرهان والإلزام.

“The primary instruments in ‘ilm al-kalam are two things: (i) proof (burhan), and (ii) refutation (ilzam).” (‘Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi, ibid., p. 151)

Thus, kalam employs both burhan for constructive argumentation and ilzam for deconstructive refutation.

Ibn as-Salah at one point clarifies the respective contexts for each method:

الإلزام يصلح للمناظر في مقام الجدل دون مقام التحقيق

“Ilzam is suitable for the debater (munazir) in the context of dialectical debate (jadal), but not in the context of verification or thorough investigation (tahqiq).” (Ibn as-Salah, 2011, Sharh mushkil al-Wasit, ed. ʻAbd al-Munʻim Khalifa Ahmad Bilal, Riyadh: Dar Kunuz Ishbilya li-n-Nashr wa-t-Tawziʻ, Vol. 2, p. 211)

Finally, there are certain situations in which scholars even considered ilzam to be preferable to burhan. Najm ad-Din at-Tufi (d. 716/1316) provides such an example. He argues that against the notion of absolute free will (qadar), ilzam should be employed instead of demonstrative methods due to the topic’s inherent complexity and the limitations of human comprehension:

اعلم أن هذه المسألة، أعني مسألة القدر، هي سر من أسرار الله سبحانه، لا سبيل لبشر إلى الاطلاع على كنهه وحقيقته، إلا إن شاء الله. […]

وإنما غرضنا وغرض غيرنا بالكلام فيها دفع شبه الخصوم […]. فإذا تبين بطلانها، رجع الشخص إلى ما جاء به الشرع، من الإيمان والتسليم، بقلب من الشبهات نقي سليم. […]

فلهذا، كل من وقفنا على كلامه في هذه المسألة من القدرية، إنما نجيبهم بالمدافعات والإلزامات، بأن نبين أن الاشكال الذي يوردونه لازم عليهم، ولا نأتي في توجيه حقيقة المسألة بما يمثل إليه العقل مثله إلى شبه الخصوم.

“Know that this issue, I mean the issue of free will (qadar), is one of the mysteries (asrar) of Allah the Most Glorified, the nature (kunh) and reality (haqiqa) of which no human being has a route to realise, except by the will of God. […]

“Indeed, our objective, and the objective of others, in discussing it is to respond to the fallacies of opponents […]. Once their falsehood is made apparent, one will revert to what revealed religion (shar‘) stipulates, namely having belief (iman) and acquiescent assent (taslim) in a heart that is clear (naqiyy) and free (salim) of fallacies (shubuhat) […].

“Therefore, when we address the discussions of Qadaris on this issue, we only respond to them in the manner of rebuttal (mudafa‘a) and ilzam, by showing that the dubiety (ishkal) that they raise will in fact apply to their own position. We will not seek to establish the truth on this issue positively by affirming something that the mind leads to in the same way it leads to the fallacies of our opponents.” (at-Tufi, 2005, Dar’ al-qawl al-qabih bi-t-tahsin wa-t-taqbih, ed. Ayman Mahmud Shihadah, Riyadh: Markaz al-Malik Faysal li-l-Buhuth wa-d-Dirasat al-Islamiyya, p. 163)

at-Tufi’s position clarifies certain theological topics might be better addressed through the indirect refutations offered by ilzam, particularly when engaging with those holding opposing views.

Ibn Rushd (d. 595/1198), the influential philosopher and Maliki jurist, offers a complementary perspective in his Fasl al-maqal that acknowledges the pragmatic necessity of different forms of argumentation based on the diverse cognitive capacities of different audiences:

طباع الناس متفاضلة في التصديق: فمنهم من يصدق بالبرهان، ومنهم من يصدق، بالأقاويل الجدلية تصديق صاحب البرهان بالبرهان، إذ ليس في طباعه أكثر من ذلك

“The natures of humans are on different levels with respect to [their paths to] assent. One comes to assent through demonstration; another comes to assent through dialectical arguments, just as firmly as the demonstrative man through demonstration, since his nature does not contain any greater capacity”. (Ibn Rushd, 1983, Fasl al-maqal fi-ma bayna l-hikma wa-sh-shariʻa mina l-ittisal, ed. Muhammad ʻImara, Cairo: Dar al-Maʻarif, p. 31)

This perspective from Ibn Rushd suggests that the choice between demonstrative and dialectical methods should not only consider the subject matter but also the cognitive capacities and predispositions of the audience. It provides a pragmatic justification for the coexistence of multiple argumentative approaches within Islamic theological discourse, recognising that different individuals may require different paths to arrive at the same truths.

III. D. 2. The Promised Messiah’sas approach

The Promised Messiah’sas approach reflects a nuanced understanding of the distinction between ilzam and tahqiq or burhan, recognising their respective roles and strategic applications within theological debate.

Munshi Nabi Bakhsh narrates the Promised Messiah’sas instructions regarding the use of these two types of responses:

حضرت مجھ کو عیسائیوں کے اعتراضات کے جوابات دو قِسم کے دیا کرتے تھے۔ الزامی اور تحقیقی۔ الزامی جوابات کے متعلق آپ کا ارشاد یہ ہوتا تھا کہ جب تم کسی جلسۂ عام میں پادریوں سے مباحثہ کرو تو ان کو ہمیشہ الزامی جواب دو۔ اس لئے کہ ان لوگوں کی نیّت نیک نہیں ہوتی۔ اور لوگوں کو گمراہ کرنا اور اسلام سے بد ظن کرنا اور آنحضرت صلّی اللہ علیہ وآلہٖ وسلّم پر حملہ کرنا مقصود ہوتا ہے۔ پس ایسے موقع پر الزامی جواب ان کے منہ کو بند کر دیتا ہے۔ اور عوام جو اس وقت محض تماشے کے طور پر جمع ہو جاتے ہیں۔ ایسے جواب سے متأثر ہو کر ان کے فریب میں نہیں آتے۔ لیکن اگر کسی ایسے شخص سے گفتگو کرو۔ جو اُن کے پھندے میں پھنس چکا ہو یا جس پر ایسا شبہ ہو کہ وہ اُس پر یہ ڈورے ڈال رہے ہیں تو اس کو ہمیشہ تحقیقی جواب پہلے دو۔ اور اس پر مقابلہ کر کے دکھاؤ کہ اسلام اور عیسائیت کی تعلیم میں کیا فرق ہے۔ ایسے لوگوں کو اگر الزامی جواب پہلے دیا جائے تو وہ یہ ٹھوکر کھا سکتے ہیں کہ حقیقی جواب کوئی نہیں۔

“The Promised Messiahas used to provide me with two types of responses to the objections raised by Christians: dialectical (ilzami) and demonstrative (tahqiqi). Regarding the ilzami responses, he would instruct that when you are engaging in a public debate with Christian missionaries, always use the ilzami argument. This is because their intentions are not sincere; their aim is to mislead people, create doubts about Islam, and attack the Holy Prophetsa. In such situations, the ilzami argument effectively silences them, and the general public, who often gather merely out of curiosity, are not influenced by their deception. However, if you are speaking with someone who has already fallen into their trap or whom you suspect they are trying to influence, always start with a tahqiqi argument. Show through reason and comparison the differences between the teachings of Islam and Christianity. If you start with an ilzami argument in such cases, they might mistakenly think that there is no real, substantive answer to their objections.” (Ya‘qub ‘Ali ‘Irfani, 2013, Hayat-e Ahmad, Rabwah: Nizarat-e Isha‘at, Vol. 1, pp. 412-413)

This narration highlights the Promised Messiah’sas nuanced understanding of the strategic application of ilzam and tahqiq in different contexts. He recognised that while ilzami arguments could effectively counter insincere opponents in public settings, tahqiqi arguments, focusing on demonstrative reasoning, were more appropriate for engaging with individuals seeking genuine understanding.

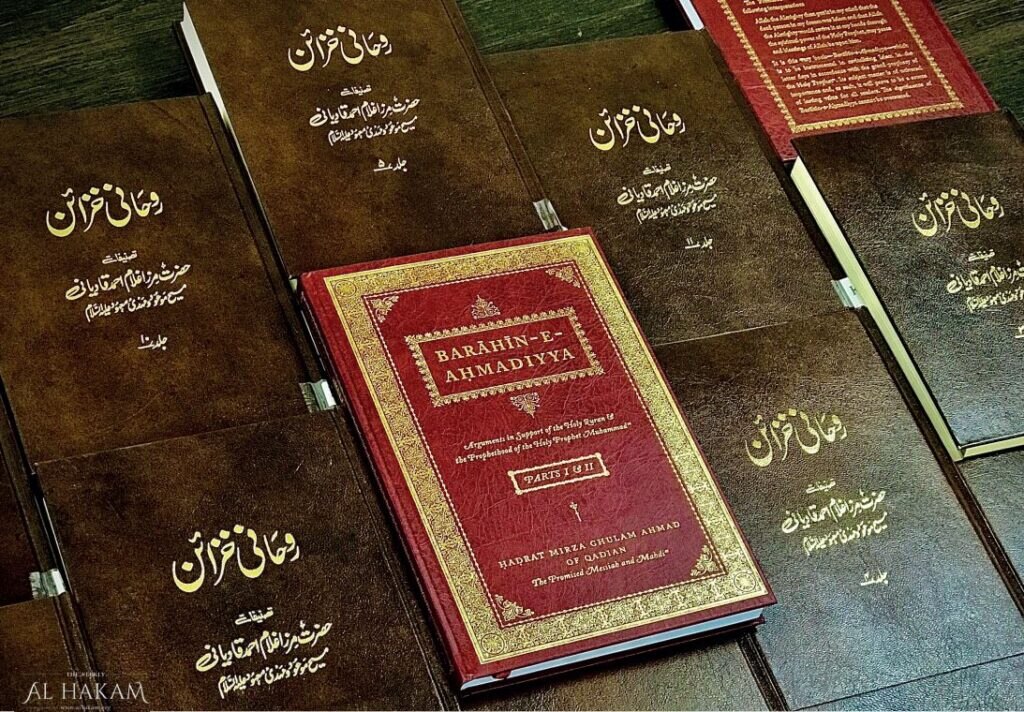

In Barahin-e Ahmadiyya, the Promised Messiahas writes:

شاید بعض صاحبوں کے دل میں اس کتاب کی نسبت یہ وسوسہ گزرے کہ جواب تک کتابیں مناظرات مذہبی میں تصنیف ہو چکی ہیں کیا وہ الزام اور افحام مخاصمین کے لئے کافی نہیں ہیں کہ اس کی حاجت ہے لہذا میں اس بات کو بخوبی منقوش خاطر کر دینا چاہتا ہوں جو اس کتاب اور ان کتابوں کے فوائد میں بڑا ہی فرق ہے وہ کتابیں خاص خاص فرقوں کے مقابلہ پر بنائی گئی ہیں اور ان کی وجوہات اور دلائل وہاں تک ہی محدود ہیں جو اس فرقہ خاص کے ملزم کرنے کے لئے کفایت کرتی ہیں اور گو وہ کتابیں کیسی ہی عمدہ اور لطیف ہوں مگر ان سے وہی خاص قوم فائدہ اٹھا سکتی ہے کہ جن کے مقابلہ پر وہ تالیف پائی ہیں لیکن یہ کتاب تمام فرقوں کے مقابلہ پر حقیت اسلام اور سچائی عقائد اسلام کی ثابت کرتی ہے اور عام تحقیقات سے حقانیت فرقان مجید کی بپایہ ثبوت پہنچاتی ہے اور ظاہر ہے کہ جو جو حقائق اور دقائق عام تحقیقات میں کھلتے ہیں خاص مباحثات میں انکشاف ان کا ہر گز ممکن نہیں کسی خاص قوم کے ساتھ جو شخص مناظرہ کرتا ہے اس کو ایسی حاجتیں کہاں پڑتی ہیں کہ جن امور کو اس قوم نے تسلیم کیا ہوا ہے ان کو بھی اپنی عمیق اور مستحکم تحقیقات سے ثابت کرے بلکہ خاص مباحثات میں اکثر الزامی جوابات سے کام نکالا جاتا ہے اور دلائل معقولہ کی طرف نہایت ہی کم توجہ ہوتی ہے اور خاص بحثوں کا کچھ مقتضاہی ایسا ہوتا ہے جو فلسفی طور پر تحقیقات کرنے کی حاجت نہیں پڑتی اور پوری دلائل کا تو ذکر ہی کیا ہے بستم حصہ دلائل عقلیہ کا بھی اندراج نہیں پاتا۔

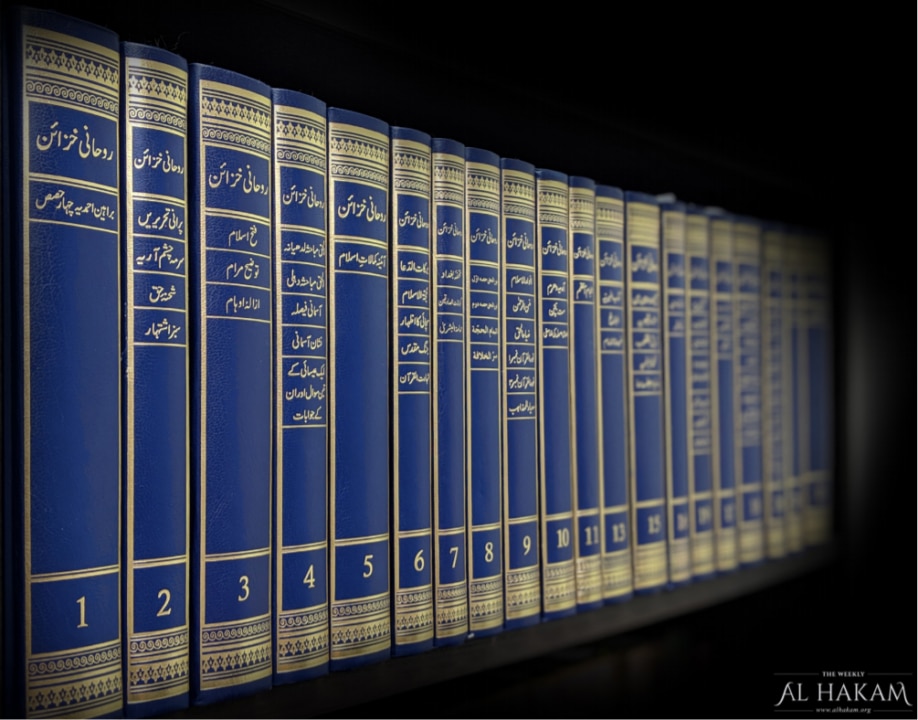

“Some people may harbour doubts about this book and ask, ‘Are the books that are already written on religious subjects (munazarat) not sufficient to refute (ilzam) and silence (ifham) the critics? Why do we need another book?’ Let it be clear that this book is unlike any other in its effectiveness. All those books have been written in the context of a particular faith and their arguments are confined to refuting (ilzam) the specific beliefs of that faith. No matter how great or scholarly those books may be, they serve only the people to whom they have been addressed. This book, on the other hand, proves the divine origin of Islam and the superiority of the teachings of Islam over all faiths and establishes the authenticity of the Holy Quran through comprehensive demonstrations (tahqiqat). It is obvious that truths that unfold in such a manner can never be revealed through focussed arguments. When debating with the people of a particular faith, one does not need to provide in-depth and solid demonstrations (tahqiqat) regarding beliefs that they already hold; instead, one relies primarily on dialectical (ilzami) answers, and rarely resorts to logic and reason (dala’il-e ma‘qula). By their very nature, such debates do not necessitate philosophical demonstrations (tahqiqat), let alone exhaustive reasoning. Only a fraction of rational arguments (dala’il-e ‘aqliyya) is employed in such debates.” (Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Barahin-e Ahmadiyya: Part 1, in: Id., 2021, Ruhani Khaza’in, Farnham: Islam International Publications, Vol. 1, pp. 8-9)

The Promised Messiah’sas approach demonstrates a nuanced understanding of ilzam and tahqiq, i.e., burhan. He writes:

اس بات کو کون نہیں جانتا کہ بحث مباحثہ اظہار حق کی غرض سے ہونا چاہئے یعنے اس نیت سے کہ اگر حق ظاہر ہو تو اسے قبول کرلیں مگر وہ شخص جو ایک بات کو اپنے لئے تو جائز رکھتا ہے لیکن اگر فریق مخالف کے کسی امر مسلم میں اس کے ہزار جز میں سے ایک جز بھی پائی جائے اور کیسی یہ خوبی سے پائی جائے تب بھی اس کو قبول نہیں کرتا ایسے شخص کی نیت ہرگز بخیر نہیں ہوتی اور جو وقت اس کے ساتھ بحث میں خرچ ہو وہ ناحق ضائع جاتا ہے پس کیا یہ ُ بری بات ہے کہ ایسے شخص کو سمجھایا جائے کہ بھائی جبکہ تو خود آپ ہی ایسی باتوں کو مانتا ہے کہ نہ صرف بالاتر از عقل بلکہ خلاف عقل بھی ہیں تو جو امور عقلِ محدود انسانی سے بالاتر ہیں اور ان کا ثبوت بھی تجھے دیا جاتا ہے۔ ان کے ماننے میں تجھے کیوں تامل ہے بلکہ تمام تر دینداری و پرہیزگاری تو اس میں ہے کہ اگر انسان ایک بات کو اپنی رائے میں صحیح سمجھتا ہے تو اسی نوع کی بات میں اپنے مخالف کے ساتھ منکرانہ جھگڑا نہ لے بیٹھے کہ یہ اوباشانہ طریق ہے جس میں فریقین کی تضیع اوقات ہے پھر پر ظاہر ہے کہ ایسا جھگڑا کس قدر برا اور خلاف طریق انصاف ہوگا کہ ایسی بات سے انکار کیا جائے کہ جو اپنے مسلّمات سے صدہا درجہ صاف اور پاک اور قدرت الٰہی میں داخل اور تاریخی طور پر ثبوت بھی اپنے ساتھ رکھتی ہو۔ بے شک ایسا نکما جھگڑا کرنے والا اپنا اور اپنے مخالف کا وقت عزیز کھونا چاہتا ہے جس کو الزامی جواب سے متنبہ کرنا اپنے حفظِ اوقات کے لئے فرض طریق مناظرہ ہے اور نیز چونکہ دنیا میں مختلف طبیعتوں کے آدمی ہیں بعض لوگ جو نادر الوجود ہیں وہ تحقیقی بات سن کر اپنی ضد چھوڑ دیتے ہیں اور اکثر عوام جو تحقیقی جواب سمجھنے کا مادہ ہی نہیں رکھتے یا بعض ان میں سے کچھ مادہ تو رکھتے ہیں مگر چاند پر خاک ڈالنا چاہتے ہیں اس لئے ان کا مونہہ الزامی جوابوں سے بند ہوتا ہے یہی وجہ ہے کہ الزامی طور پر چند مسلّمات آپ کے آپ کو سنائے گئے ورنہ اصل مدار جواب کا تو تحقیق پر ہی ہے۔

“Everyone knows that debates (bahth mubahatha) should be conducted with the intention of revealing the truth, meaning with the intention that if truth becomes manifest, one should accept it. However, a person who considers something permissible for himself, but if even a thousandth part of that same thing is found in an established matter of the opposing party, no matter how excellently it is found, still does not accept it – such a person’s intention is never good, and any time spent debating with him is wasted. So, is it not appropriate to explain to such a person, ‘Brother, when you yourself believe in such matters that are not only beyond reason but also contrary to reason, then why do you hesitate to accept those matters which are beyond limited human intellect and for which proof is also provided to you?’ In fact, true religiosity and piety lie in this: if a person considers something correct in his opinion, he should not engage in a contentious argument with his opponent over a similar matter, for this is a vulgar method that wastes the time of both parties. Moreover, it is evident how wrong and contrary to the principles of justice it would be to deny a matter that is hundreds of times clearer and purer than one’s own accepted beliefs, falls within divine power, and carries historical proof. Undoubtedly, such a futile arguer wishes to waste his own and his opponent’s precious time, and it is obligatory in the method of debate to alert him with a dialectical (ilzami) response to preserve one’s time. Furthermore, since there are people of different natures in the world – some rare individuals who abandon their stubbornness upon hearing a demonstrative (tahqiqi) argument, and many common people who either lack the capacity to understand tahqiqi responses or some who have some capacity but wish to cast dust on the moon [i.e., deny the obvious merit] – their mouths are shut with ilzami responses. This is why a few of your accepted beliefs were presented to you in an ilzami manner; otherwise, the main focus of the response shall be on demonstration (tahqiq).” (Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Surma-e Chashm-e Arya, in: Id., 2021, Ruhani Khaza’in, Farnham: Islam International Publications, Vol. 2, pp. 130-131)

This passage reveals the Promised Messiah’sas emphasis on establishing truth through demonstrative means (tahqiq) as the primary focus. He viewed ilzam as a secondary tool, best reserved for specific situations or types of opponents.

Hazrat Mirza Bashir Ahmad’sra narration in Sirat al-Mahdi further supports this view:

ڈاکٹر میر محمد اسماعیل صاحب نے مجھ سے بیان کیا کہ حضرت مولوی نور الدین صاحب خلیفہ اولؓ میں یہ ایک خاص بات تھی کہ معترض اور مخالف کو ایک یا دو جملوں میں بالکل ساکت کر دیتے تھے اور اکثر اوقات الزامی جواب دیتے تھے۔ لیکن حضرت مسیح موعود علیہ السلام کا یہ طریق تھا کہ جب کوئی اعتراض کرتا تو آپ ہمیشہ تفصیلی اور تحقیقی جواب دیا کرتے تھے اور کئی کئی پہلوؤں سے اس مسئلہ کو صاف کیا کرتے تھے۔ یہ مطلب نہ ہوتا تھا کہ معترض ساکت ہو جائے بلکہ یہ کہ کسی طرح حق اس کے ذہن نشین ہو جائے۔

“Dr. Mir Muhammad Isma‘il[ra] related to me that Hadrat Mawlawi Nur ad-Din, the First Caliphra, had this special characteristic that he could silence an objector or opponent in just one or two sentences, and he often gave ilzami responses. However, the method of the Promised Messiahas was that when someone raised an objection, he would always give a detailed and demonstrative (tahqiqi) response, clarifying the issue from multiple angles. His aim was not merely to silence the objector, but rather to ensure that the truth would somehow become firmly established in their mind.” (Mirza Bashir Ahmad, 2008, Sirat al-Mahdi, Rabwah: Nizarat-e Isha‘at, Vol. 2., p. 20)

This account, alongside his own writings, reinforces the Promised Messiah’sas preference for detailed and demonstrative (tahqiqi) responses. This approach, aimed at fostering genuine understanding, aligns with the principles of burhan, which seeks to illuminate truth definitively. While acknowledging the occasional tactical necessity of ilzam, his emphasis remained firmly on demonstrative reasoning.

III. E. The legitimacy of ilzam in Islamic scholarship

While ilzam’s effectiveness in theological debate is evident, its legitimacy as a method of argumentation within the Islamic tradition has sometimes been questioned. Critics might argue that ilzam is inherently un-Islamic or intellectually dishonest, as it involves engaging with premises the arguer might not personally accept. This section will demonstrate that ilzam, far from being an unorthodox practice, is firmly rooted in established principles of Islamic jurisprudence and theological discourse.

Ibn ‘Aqil, in his discussion of permissible argumentative strategies, provides a framework for understanding the legitimacy of ilzam:

ولا يجوز أن يورد سؤالاً يتضمن إلزام خصمه ما لا يقول به؛ إلا ما تضمن إفسادا لمعنى العلة وهو الكس، أو إفساد ألفاظها وهو النقض. وكل سؤال كان للإفساد جاز أن يكون على أصل المستدل خاصة دون الملزم