Ata-ul-Haye Nasir, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

Emergence of the Ahrar

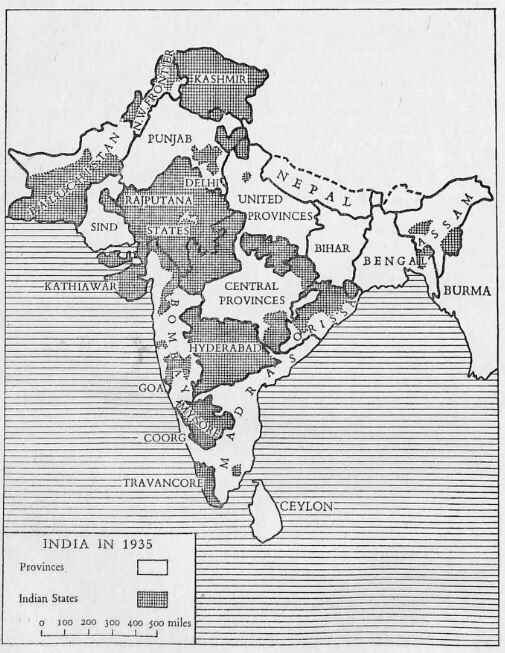

Some Muslim political activists in the All-India National Congress, who later broke away from the Congress due to some differences, joined hands and formed the Majlis-i-Ahrar-i-Islam on 29 December 1929.

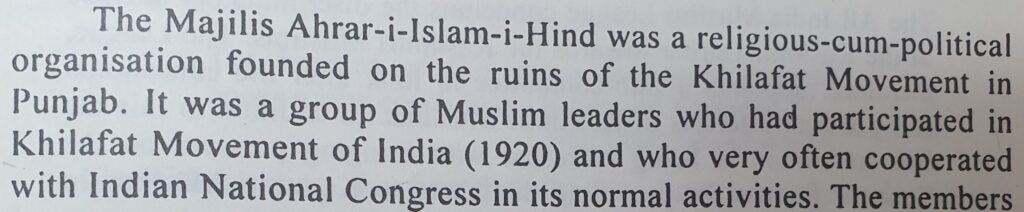

It “was a religious-cum-political organisation founded on the ruins of the Khilafat Movement in Punjab. It was a group of Muslim leaders who had participated in Khilafat Movement of India,” and “very often cooperated with Indian National Congress in its normal activities.” (Kashmir’s Struggle for Independence (1931-1939), Muhammad Yusuf Ganai, Gulshan Books, 2003, p. 102)

The founding members of the Ahrar were Maulvi Zafar Ali Khan, Maulvi Dawood Ghaznavi, Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari, Chaudhry Afzal Haq, Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar, Khwaja Abdur Rahman Ghazi, and Maulvi Habib-ur-Rahman Ludhianvi.

The Ahrar movement gathered “a group of Indian nationalists of the Moslem faith, who had found it unpalatable to work with the ‘Congress’ party.” (Coll 6/11 ‘Hejaz-Nejd Affairs: Economic Development in the Hejaz’ [27r] (54/504), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/L/PS/12/2077, in Qatar Digital Library, www.qdl.qa [accessed 22 September 2023])

Although the Ahrari leaders were pro-Congress, “they felt the need to establish a separate party, because they deemed it wise for them to be identified as a Muslim party from its name. Thus, on the suggestion of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the nationalist ulema laid the foundation of the Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam.” (Khuli Chitthi Banaam Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind wa Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam [Taqdim by Muhammad Jalaluddin Qadri], Maktaba-e-Rizwiyyah, Lahore)

Hence, “Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari was elected its first president. In December 1929, the Congress passed the resolution of complete self-government, and in April 1930, it initiated the Salt Satyagraha. The Ahrar were mentally consorted with the Congress, they left their own organisation unattended, and accompanied the Congress in the civil disobedience.” (Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari: Sawaneh wa Afkar, by Agha Shorish Kashmiri, Matbu‘at-e-Chitan, Lahore, p. 98)

Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar states that initially, the Ahrar had “no disagreement with the Congress,” and their prominent leaders “endured imprisonment during the civil disobedience movement in 1930,” which was led by the Congress. (Khutbat-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, compiled by Agha Shorish Kashmiri, Maktaba-e-Ahrar, Lahore, 1944, p. 145)

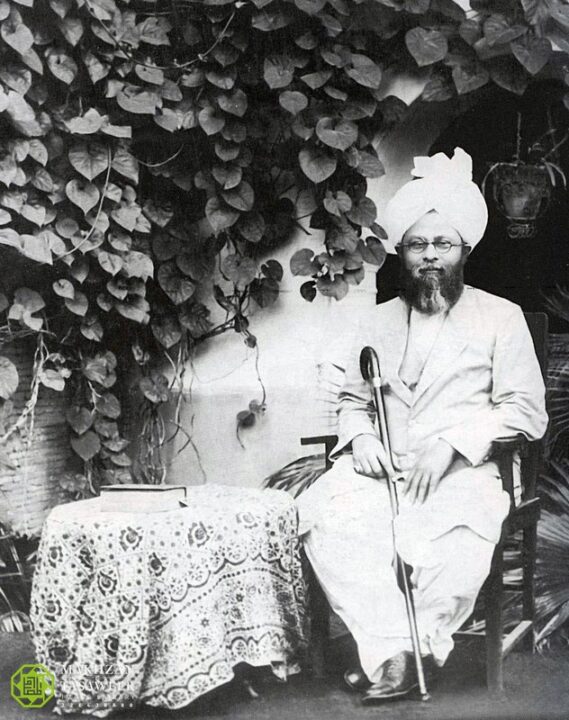

In May 1930, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud, Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra advised Muslims to refrain from such unlawful acts:

“The best option for the Muslims is to oppose any breach of the law and to urge the government to fulfil their demands.” The Muslims “ought to prove that they also desire the country’s freedom, just like the Hindus.” Ahmadi Muslims “should support Muslim rights in particular and the country’s rights in general,” and ought to “confront those who disrespect the law. Such people are not the country’s well-wishers, but rather, they are its enemies. They must be confronted in order to discourage the ideology that undermines the country’s freedom.” (A letter to the Viceroy, 1930: Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’s efforts in preventing Indian Muslims from indulging in agitation and violence”, Al Hakam, 5 May 2023, Issue 268, pp. 14-17)

Ahrar’s anti-Ahmadiyya campaign

Chaudhry Afzal Haq, known as the Mufakkir-e-Ahrar, has stated that opposition to Ahmadiyyat “was an important part of the Ahrar’s tabligh.” (Tarikh-e-Ahrar, Maktaba-e-Majlis Ahrar-e-Islam Pakistan, 1968, p. 198)

The Ahrar initiated the anti-Ahmadiyya campaign, and as soon as this propaganda emerged as one of their strongest sentiments, they started to gain popularity amongst the Indian Muslims. While the Ahrar were taking gradual steps in their opposition to Ahmadiyyat, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra expressed:

“There is no doubt that we are less in number, however, being in the minority can never be a cause for fear. It is mentioned in the Holy Quran: کَمۡ مِّنۡ فِئَۃٍ قَلِیۡلَۃٍ غَلَبَتۡ فِئَۃً کَثِیۡرَۃً [‘How many a small party has triumphed over a large party’ (Surah al-Baqarah, Ch. 2: V. 250)], meaning that it has always been a practice in the world that the small truthful communities became victorious over hugely large parties. If it is true that we are a community that has been established by God Almighty, we will certainly be victorious in the world despite being in the minority.” (Khutbat-e-Mahmud, Vol. 12, p. 396)

Reasons behind the opposition

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, since its beginning, has been at the forefront of serving the Muslim cause. For instance, when the Shuddhi Movement reached its peak in 1923, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya greatly served the Muslim Cause to prevent the mass conversions of the Malkana Muslims to Hinduism. For more details, see “Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’sra response to the Shuddhi movement and the Jamaat’s relentless services for Islam”, Al Hakam, 17 December 2021, Issue 196, pp. 18-20)

Similarly, when the plight of the Kashmiri Muslims reached its peak, Ahmadis were seen at the forefront of striving for their rights. The Ahrar considered it a great ‘threat’ to their political aspirations. Thus, they harboured an agitation against Ahmadiyyat.

All-India Kashmir Committee

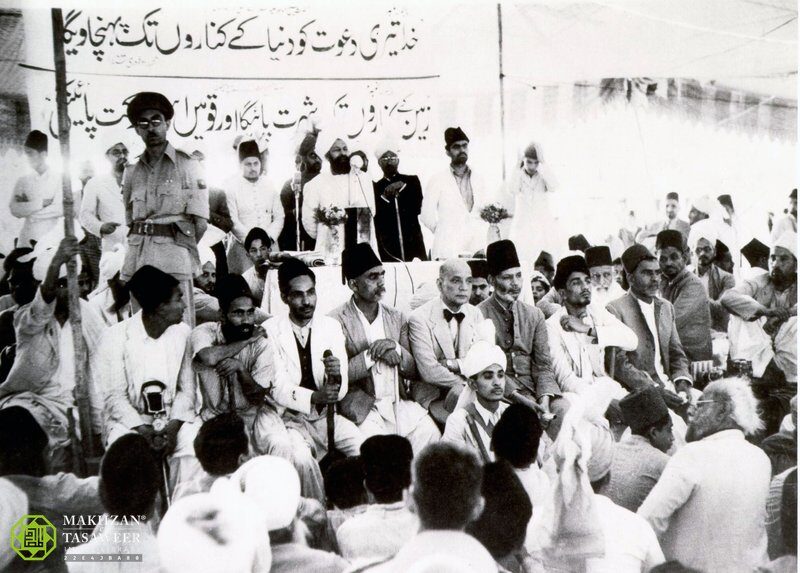

In 1931, prominent Muslim leaders gathered in Simla and formed the All-India Kashmir Committee, and Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra was unanimously elected as its president.

As soon as the charge of this committee was handed over to Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, a new wave of awareness and awakening regarding the rights of Kashmiri Muslims spread across India. Kashmir Day started to be celebrated all over India with the participation of people belonging to every Islamic school of thought. Huzoorra himself offered the most generous financial help. Upon Huzoor’sra encouragement, Muslims all over India began funding the Kashmir movement. Huzoor’sra efforts proved unparalleled, even at the level of negotiations and dialogue with the authorities.

For more details, see “Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s Services to the Muslim Cause: Guidance for Turkey, peace in the Arab World and the Kashmir Movement” (Al Hakam, 19 February 2021, Issue 153, pp. 41-44).

Ahrar’s reaction

Upon seeing the situation, Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam realised that Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya was a force against whom they would never be able to achieve their nefarious goals:

“To the chagrin of the Ahrars, Bashiruddin Mahmud[ra], leader of the Qadian section of the Ahmadis, was appointed president of the committee on Iqbal’s recommendation. […] The fact of an Ahmadi at the helm was an excuse to damn the All-India Kashmir Committee as a British plan to sabotage efforts to enlist Kashmir into a larger Muslim whole.” The Ahrar’s act of “discrediting the committee as an outpost of Qadian proved ineffective,” because “even the Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Hind decided to cooperate with the Kashmir Committee.” (Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Ayesha Jalal, Routledge, 2000, p. 356)

The Al-Adl of Gujranwala, dated 9 August 1931, alleged that the Kashmir Committee had been formed at British insistence since “the Ahmadis never participate in movements that criticise the policy of Government.” (Ibid, p. 358)

Thus, “the Ahrar leaders did not endorse the constitution of this Kashmir Committee,” in fact, “they were against Mirza Bashir-ud-Din[ra], who was chief of the Ahmadiya sect. The Ahrar, considering the people belonging to the Ahmadiya sect to be non-Muslims, felt that they had no right to speak for the Muslim community. Secondly, Ahrar leaders considered Ahmadiyas to be planted by the British, and therefore, they felt that Ahmadiya would serve the interests of the British in Kashmir. They also feared that the Ahmadiyas might establish an Ahmadiya state with the aid of the British in Kashmir.” (Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2011), p. 92)

This baseless and false idea has been floated by Shorish Kashmiri as well, who states that the British Government “convinced Allama Iqbal to join their ranks, and laid the foundation of the All-India Kashmir Committee. […] Mirza Mahmud Ahmad[ra] became its president; however, the Ahrar protested it, [and] naturally found a political ground which they were in need of to build up their stature as a separate party.” (Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari: Sawaneh wa Afkar, Matbu’at-e-Chitan, Lahore, pp. 101-102)

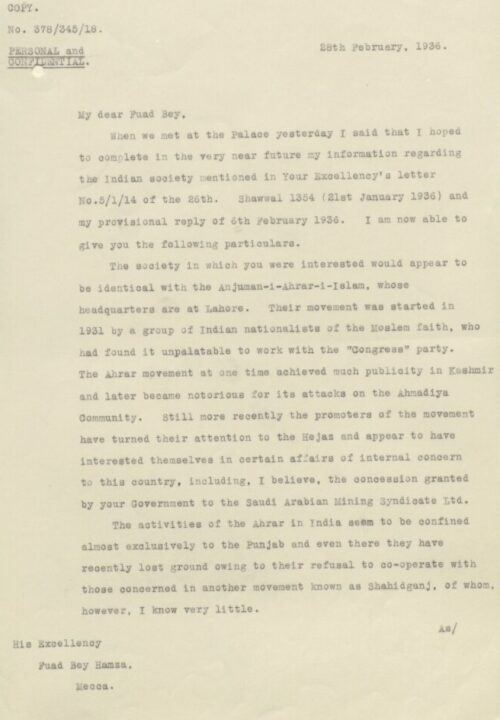

On 28 February 1936, Indian Government’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Saudi Arabia, Sir Andrew Ryan, wrote to the then Undersecretary of Saudi Arabian Foreign Affairs, His Excellency Fuad Bey Hamza, and provided information about Majlis-e-Ahrar as requested by Fuad Bey on 21 January. He mentioned the Ahrar’s opposition to Ahmadiyyat as well:

“The Ahrar movement at one time achieved much publicity in Kashmir and later became notorious for its attacks on the Ahmadiya Community.” (Coll 6/11 ‘Hejaz-Nejd Affairs: Economic Development in the Hejaz’ [27r] (54/504), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/L/PS/12/2077, in Qatar Digital Library, www.qdl.qa [accessed 22 September 2023])

In addition to the agitational politics, another plank of Ahrar’s ideology was “their move to declare Ahmadis as non-Muslims.” And “the Ahmadi involvement in the movement for Muslim rights in Kashmir intensified the Ahrar’s opposition to the Ahmadiya community.” (“The Pre-History of Religious Exclusionism in Contemporary Pakistan: ‘Khatam-e-Nubuwwat’ 1889–1953.” Modern Asian Studies 49, no. 6 (2015): 1840–74. www.jstor.org/stable/24734820.)

Ahrar create disorder in Sialkot

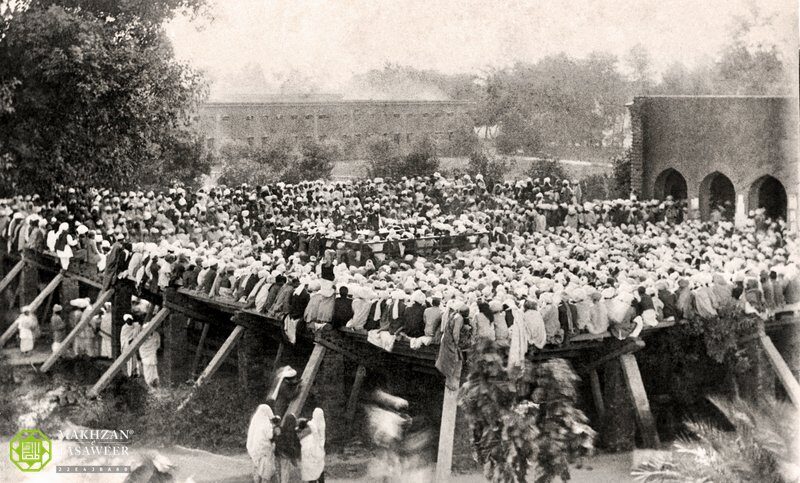

Following a session of the All-India Kashmir Committee, a public jalsa was organised by the Committee on 13 September 1931, where Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra was to deliver the keynote address.

While the president of the session began his welcome address, some mischievous individuals belonging to the Ahrar started making a hue, and police asked them to move away from the gathering. However, they began throwing stones at the gathering. Huzoorra was yet to arrive at the venue, and the administration of the jalsa informed Huzoorra about the situation and requested to not come to the jalsa. However, Huzoorra did not agree and came to the stage while the stones were still being thrown at the jalsa.

Upon seeing Huzoorra on the stage, the Ahrar intensified their vile act, and since most of the Ahmadis were seated around the stage, they were affected the most. The young Ahmadis made a circle around Huzoorra, but the Ahrar were throwing stones with such intensity that three stones hit Huzoor’s hand as well. Around 25 to 30 Ahmadis were seriously injured, and many others received minor injuries.

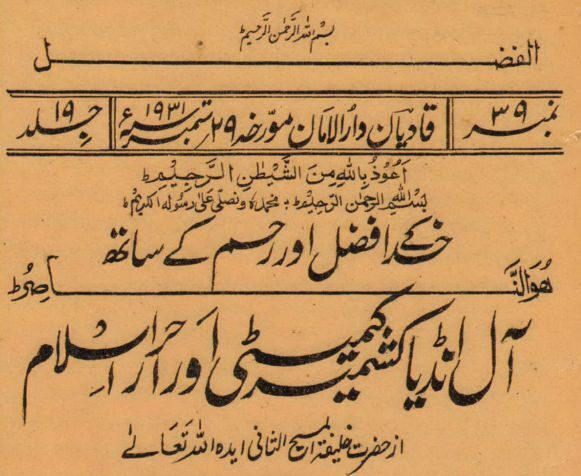

After an hour or so, once the situation calmed, Huzoorra delivered his speech. (Al Fazl, 20 September 1931, pp. 3-4)

Huzoorra narrated the details of the establishment of the Kashmir Committee, and stated that he wrote letters to the Ahrar leaders, such as Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar and Chaudhry Afzal Haq, and invited them to join the Committee. They did not even respond; however, Huzoorra came to know from other sources that they did not want to work with Ahmadis. Later on, when they were invited to cooperate in relation to Kashmir Day on 14 August 1931, they objected that since the president of the All-India Kashmir Committee was the Imam of the Ahmadiyya Jamaat, they were not willing to work along with it.

Upon this, Huzoorra wrote letters to Allama Iqbal, Maulvi Muhammad Ismail Ghaznavi, and Maulvi Ghulam Rasul Mehr, and said that if his being the president was the only cause of concern for the Ahrar, he was ready to resign from the presidency, provided they convinced the Ahrar to join the Committee and act according to the strategy of the Muslim majority. However, the Ahrar responded that they would work separately. (Al Fazl, 24 September 1931, p. 4)

Towards the end, Huzoorra said:

“I advise the Ahrar that – if anyone is present here from them, they ought to convey to their fellows – I do not care about these stones and do not hold any reactionary anger against them. There is still time; they ought to refrain from such acts for the sake of the oppressed brethren of Kashmir. They should come [to make peace], and I am ready to leave the presidency, but they must promise to obey the decisions of the Muslim majority. We have witnessed their morals today, and they can come to witness ours. I assure them that even after leaving the presidency, myself and my Jamaat will support them more than their own people. Presidency does not hold any significance to me; honour is attained by serving, [as it is stated by the Holy Prophetsa:] سید القوم خادمھم. […]

“I already have immense responsibilities. I am the Imam of such a great Jamaat and have to work so much that I rarely get the opportunity to sleep before 12 or 1 at night. I have accepted this duty [Kashmir Committee’s presidency] only with the thought that the future generations of Kashmir would pray for us, and say that may Allah the Almighty bless those through whose efforts we are living a peaceful life. They [Ahrar] also have this opportunity to be the recipients of the prayers of Kashmiris.” (Ibid, p. 9)

Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra article in response to Inqilab

On 23 September 1931, a newspaper, Inqilab, wrote an article about the Kashmir Committee and the Ahrar. In response, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra wrote an article on 24 September and expressed his views on the points mentioned by Inqilab. Huzoorra mentioned the Ahrar’s anti-Ahmadiyya propaganda and stated that they had spread a false notion during their speeches at Sialkot and other cities that the president of the Committee was using his office to preach Ahmadiyyat. (Al Fazl, 29 September 1931, pp. 3-4)

Ahrar’s campaign to declare Ahmadis as non-Muslims

Ayesha Jalal mentions that the Ahrar began a propaganda campaign among the Muslim masses that Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra was “discriminating” against the non-Ahmadi Muslims, and thus, the Ahrars “embarked upon a public campaign to expel the sect from Islam.” (Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Routledge, 2000, p. 293)

Arjun Singh, editor of the newspaper Rangeen, states in his book Sair-e-Qadian:

“Majlis-e-Ahrar […] has set aside all its previous principles just to engage in antagonistic activities against Ahmadis without any reason. Moreover, nowadays, they desire to expel Ahmadi Muslims from Islam, and perhaps in the future, they will try to banish them from their homeland and subsequently from the rest of the world. However, we firmly believe that if there is any living group among Muslims, it is the Ahmadiyya Jamaat. As we have established before, the organisation and way of life of Ahmadis ensure their protection and safety. […] As their fellow countrymen, it is our duty to tell the Ahrar that a community can never be effaced with religious compulsion. We wish to categorically tell the Ahrar that their behaviour is causing great disturbance for the neighbouring communities as well, and the non-Muslims are thinking that in the presence of people favouring religious compulsion, it is difficult and impossible for the country to attain freedom.” (Sair-e-Qadian, Sardar Press, Amritsar, pp. 29-31)

Baseless ‘fear’ which scared the Ahrar

Aziz-ur-Rahman Ludhianvi, son of Habib-ur-Rahman Ludhianvi (one of the founding members of the Ahrar), states that “the Ahrar leaders felt that through the Kashmir Committee, all Muslims would convert to” Ahmadiyyat. They even wrote to the Maharaja, assuring him of their loyalty, and alleged that the Kashmir Committee was “preparing grounds to dethrone” the Maharaja “on the behest of the British.” (Raees-ul-Ahrar Maulana Habib-ur-Rahman Ludhianvi aur Hindustan ki Jang-e-Azadi, 1961, p. 159)

Janbaz Mirza, the official historian of the Ahrar, writes that Majlis-e-Ahrar believed that the Ahmadis and the British were “harmful to Islam and the freedom of India.” Hence, “in case the leadership of Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud[ra] was acknowledged, it would have harmed not only the Faith of the 3.2 million Kashmiri Muslims, but rather, the non-Indian Muslims would also be harmed by its impact. As a consequence,” Ahmadiyyat “would have engulfed the whole of Islam.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, 1975, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, p. 182)

Chaudhry Afzal Haq, known as the Mufakkir-e-Ahrar, mentions that the most surprising fact for them was that the “Jamiat-ul-Ulema announced to cooperate” with the Kashmir Committee, and “the well-aware religious people felt the danger that the Muslims of Kashmir would become apostates through the” Ahmadi Muslim missionaries. (Tarikh-e-Ahrar, Maktaba-e-Majlis Ahrar-e-Islam Pakistan, 1968, p. 94)

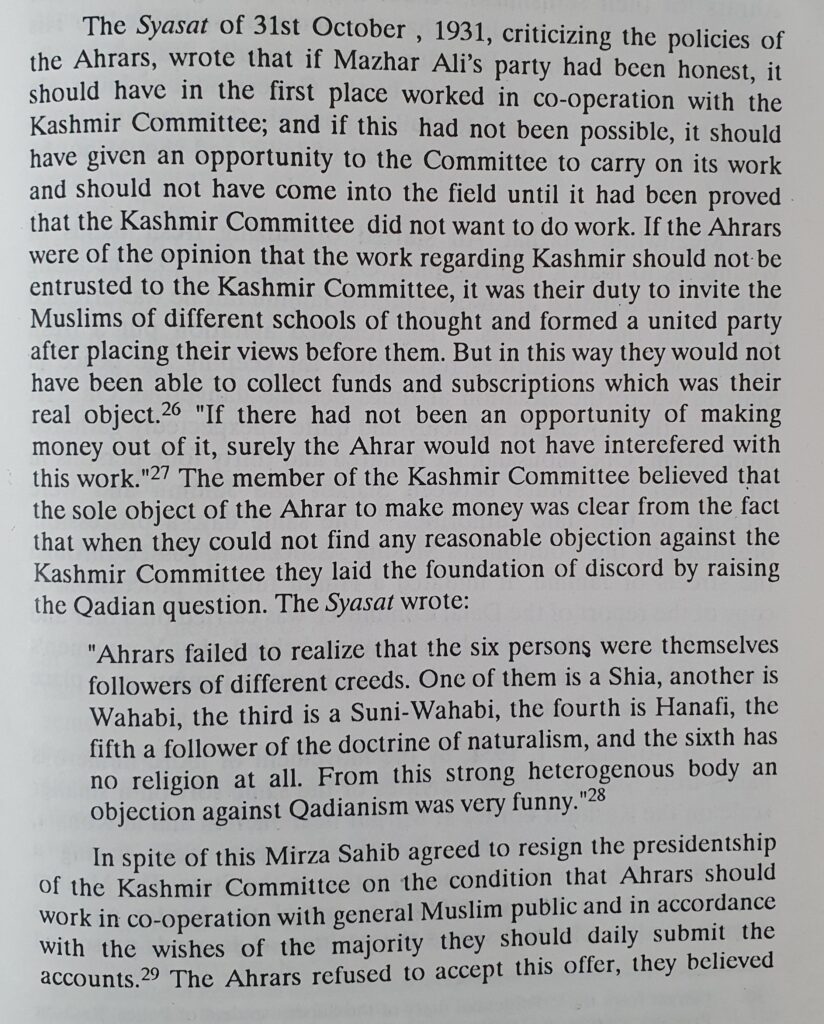

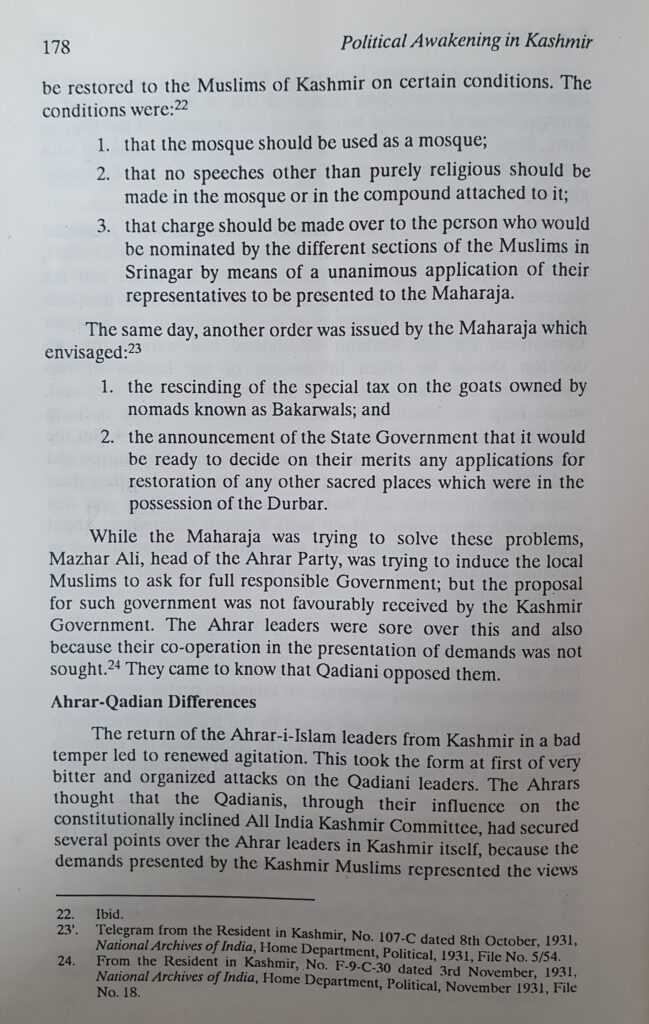

In relation to the members of the Kashmir Committee, Ravinderjit Kaur has cited an excerpt from the newspaper Siasat, which stated that the “Ahrars failed to realize that the six persons were themselves followers of different creeds. One of them is a Shia, another is Wahabi, the third is a Suni-Wahabi, the fourth is Hanafi, the fifth is a follower of the doctrine of naturalism, and the sixth has no religion at all. From this strong heterogenous body, an objection against Qadianism was very funny.” (Political Awakening in Kashmir, APH Publishing Corporation, New Delhi, 1996, p. 179)

Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra response to such assumptions

Addressing a gathering of the All-India Kashmir Committee in Sialkot, on 13 September 1931, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra responded to such false notions and said:

“One must ponder as to what really went wrong that all of these people – which included leaders, religious scholars, flag-bearers of freedom and liberation, well-versed in philosophy – joined together and [supposedly] suddenly decided, ‘Let us betray everyone so that the whole world could become Ahmadi.’ What magic did I possess that I managed to include all of them in this ‘conspiracy’? […] Only a mad person can assert that all of these leaders have carried out this collective ‘conspiracy’, and they have joined me despite being aware that ‘I will convert the non-Ahmadis to Ahmadiyyat’. The truth is that they presume that all of the wise people are among them, and the rest are mad. These people consider me an enemy of Islam; however, what is their loss if Islam can be helped through me? […] Maulvi Meerak Shah Sahib knows that Ahmadis are not even one per cent in Kashmir, but still, the rumour was spread there that ‘I wish to gain its kingdom.’ […] These are all provocative and unwise thoughts.” (Al Fazl, 24 September 1931, pp. 7-8)

During his Friday Sermon on 13 November 1931, Huzoorra mentioned the plight of the Muslims in Kashmir, and said, “I extended my help to these 3 million people, who were weak and helpless like orphans, and I did so without thinking about the progress of Ahmadiyyat through this [service].” (Al Fazl, 19 November 1931, p. 6)

Then, during a speech on 27 December 1931, Huzoorra mentioned that Ahmadis were selflessly helping the oppressed Muslims of Kashmir, and “if God Almighty inculcates love in someone’s heart towards us due to this service, we cannot deny this blessing of God Almighty, however, we cannot make it a tool to preach Ahmadiyyat.” (Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 12, pp. 405)

Civil Disobedience Movement in Kashmir by Ahrar

The peaceful movement for the rights of Kashmiri Muslims was achieving great success under the leadership of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, however, “On 1 October 1931, the Working Committee of the Majlis-e-Ahrar held its emergency meeting in Lahore, where” they “decided to initiate the civil disobedience movement in Kashmir.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, 1975, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, p. 193)

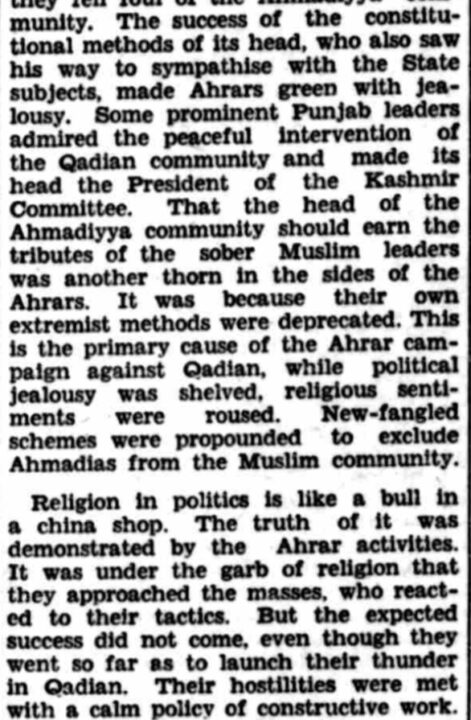

In fact, “the success of the constitutional methods of” Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra “who also saw his way to sympathise with the State subjects, made Ahrars green with jealousy. Some prominent Punjab leaders admired the peaceful intervention of the Qadian community and made its head the President of the Kashmir Committee. That the head of the Ahmadiyya community should earn the tributes of the sober Muslim leaders was another thorn in the sides of the Ahrars. It was because their own extremist methods were deprecated. This is the primary cause of the Ahrar campaign against Qadian, while political jealousy was shelved, religious sentiments were roused. New-fangled schemes were propounded to exclude Ahmadias from the Muslim community. […] It was under the garb of religion that they approached the masses, who reacted to their tactics. But the expected success did not come, even though they sent so far as to launch their thunder in Qadian. Their hostilities were met with a calm policy of constructive work.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 14 December 1937, p. 10)

A complicated situation which was faced by “both the British and the Dogra government was that the Ahrar party, watching Kashmir slipping through their fingers into the hands of the Kashmir Committee, decided to send jathas (bands of volunteers) into state territory through the Jammu province. They claimed that the Kashmir Committee was run by Ahmadiyyas for the propagation of their ‘sacrilegious’ sect in Kashmir.” (Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir, Chitralekha Zutshi, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 220)

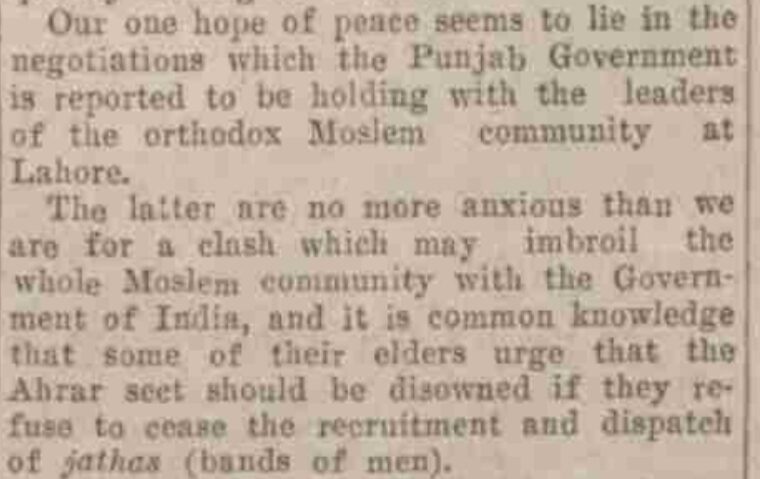

It was feared that these acts of the Ahrar would “embroil the whole Muslim community with the Government of India, and it is common knowledge that some of their elders urge that the Ahrar sect should be disowned if they refuse to cease the recruitment and dispatch of jathas (bands of men).” (Aberdeen Press and Journal, 7 November 1931, p. 7)

It was due to their unconstitutional and unlawful methods that the Ahrar leaders failed to attract the support of decent Muslim opinion for themselves in order to satisfy their ambition to exist as an individual entity. (Political Awakening in Kashmir, Ravinderjit Kaur, APH Publishing Corporation, New Delhi, 1996, p. 158)

Baseless accusation by Ahrar and Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra response

Janbaz Mirza narrates that since Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari was expressing certain opinions against the British policy in India, the Government arrested him from Delhi under Section 124. As a protest against his arrest, Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar sent a letter to the Viceroy of India, stating that “it is generally believed that Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud[ra] is the factor behind the arrest of Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari under Section 124. I have information that the Delhi government is not alone in approving the action against Shah Ji.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, 1975, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, pp. 221-222)

Refuting this false allegation, Al Fazl wrote on 27 October 1931:

“Another false notion that is being spread nowadays is that the arrest of Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari during his activities in Mughalpura occurred at the behest of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih II, may Allah be his Helper. Due to the fact that this incorrect statement is being spread widely and an attempt is being made to misguide the public, we announce that this is a completely incorrect and false statement. In this relation, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih II has stated, ‘I consider it to be against decency to hatch conspiracies of arrest and imprisonment against those with whom one has some disagreements.’ It is hoped that after this statement, no one will have any kind of misunderstanding.”

Ahrar’s desperation

In October 1931, a delegation of the Ahrar leaders presented certain demands to the Maharaja, such as the establishment of a Responsible Government in Kashmir, however, it was rejected. “The return of the Ahrar-i-Islam leaders from Kashmir in a bad temper led to renewed agitation. This took the form at first of very bitter and organized attacks on the” Ahmadi “leaders. The Ahrars thought that the” Ahmadis, “through their influence on the constitutionally inclined All India Kashmir Committee, had secured several points over the Ahrar leaders in Kashmir itself.” (Political Awakening in Kashmir, Ravinderjit Kaur, APH Publishing Corporation, New Delhi, 1996, p. 178)

Kaur further states:

“The Syasat of 31st October, 1931, criticizing the policies of the Ahrars, wrote that if Mazhar Ali’s party had been honest, it should have in the first place worked in cooperation with the Kashmir Committee; and if this had not been possible, it should have given an opportunity to the Committee to carry on its work and should not have come into the field until it had been proved that the Kashmir Committee did not want to do work. If the Ahrars were of the opinion that the work regarding Kashmir should not be entrusted to the Kashmir Committee, it was their duty to invite the Muslims of different schools of thought and form a united party after placing their views before them. But in this way, they would not have been able to collect funds and subscriptions which was their real object. ‘If there had not been an opportunity of making money out of it, surely the Ahrar would not have interfered with this work.’” (Ibid, p. 179)

Allah is the Protector of Ahmadiyyat

During his Friday Sermon on 13 November 1931, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra said that generally, the non-Ahmadi Muslim members of the All-India Kashmir Committee provided him with great support as the president of the Committee; however, “there is another group [Ahrar] that opposed us well, and in some areas they opposed us with such severity that the local Ahmadis found it difficult to even visit the markets. In some places, they even physically beat the [Ahmadi] women, children, and elderly, and it is said that they announced, ‘We would crush Ahmadiyyat, send mobs to Qadian, and make lives difficult for Ahmadis.’ However, if this Community is from God, and we firmly believe it to be so, no one can ever dare destroy it. […] It is time for us to instil diligence, wakefulness, and a spirit of faith within us, and not to frighten ourselves from these hardships, but rather, we ought to be happy that Allah the Almighty has provided means for bringing us closer to Him.

“Moreover, despite the people’s animosity towards us, it is our duty to treat them with benevolence and kindness. Ignorant is the one who says, ‘We should mistreat a certain person since they are opposing us.’ […] Thus, it is our duty to treat them in a good manner, despite them being our opponents, and not to commit any act that holds any aspect of animosity. […] Hence, the need of the time is for us to exhibit the same examples that have been taught to us by the Promised Messiahas:

گالیاں سن کر دعا دو، پا کے دکھ آرام دو

کبر کی عادت جو دیکھو تم دکھاؤ انکسار

“[‘If they abuse you, pray for them; if they hurt you, comfort them; If they show arrogance, you show humility.’ (Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya [English], Part 5, p. 201)] […]

“If we exhibit such examples, their hearts will also feel the anguish, and the sentiments of love will be inculcated in their hearts. At last, a day will come when Allah the Almighty will create perfect unity within the Muslims for their progress, and Satan will be disappointed in its efforts to create division and anxiety and will know that it is impossible to instil disunity within this community. […] So, we should never be disappointed and need to have firm faith that Allah the Almighty will create means for the betterment of the Muslims and will inculcate unity among them for their progress. Only those people who are followers of Satan get disappointed, whereas the beloved ones of God are always those who never get disappointed in His mercy.” (Khutbat-e-Mahmud, Vol. 13, pp. 285-287)

Maharaja’s announcement and Ahrar’s behaviour

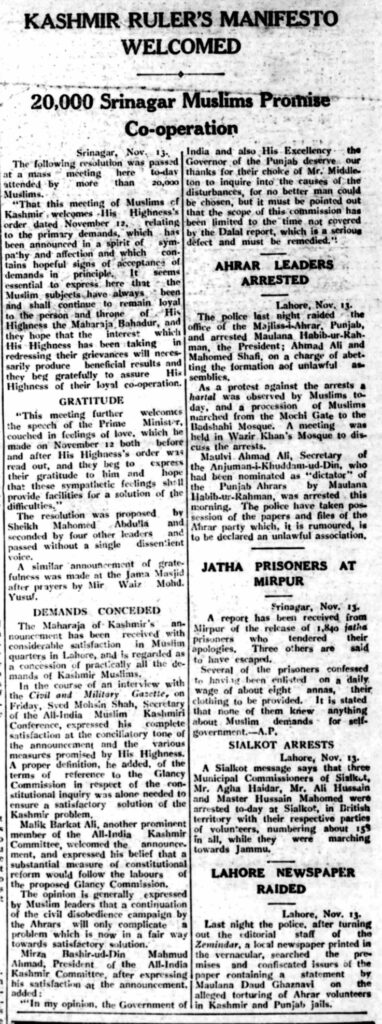

On 12 November 1931, the Maharaja of Kashmir made an announcement and promised the Kashmiri Muslims to accept certain demands of them. The Maharajah “ordered that matters of immediate concern are to be inquired into before the handling of the question of constitutional reform by the Commission over which Sir Reginald Glancy is to preside.” (The Yorkshire Post, 13 November 1931, p. 9)

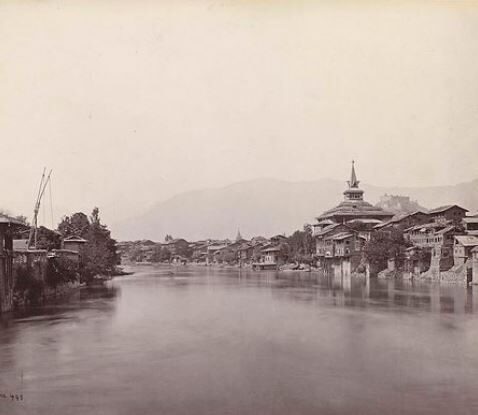

The next day, on 13 November, more than 20,000 Muslims gathered in Srinagar and passed a resolution to welcome this step from the Maharaja. However, it was “expressed by Muslim leaders that a continuation of the civil disobedience campaign by the Ahrars will only complicate a problem that is now in a fair way towards [a] satisfactory solution.

“Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, President of the All-India Kashmir Committee, after expressing his satisfaction at the announcement, added:

“‘In my opinion, the Government of India and also His Excellency the Governor of the Punjab deserve our thanks for their choice of Mr. Middleton to inquire into the causes of the disturbances, for no better man could be chosen, but it must be pointed out that the scope of this commission has been limited to the time not covered by the Dalal report, which is a serious defect and must be remedied.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 15 November 1931, p. 1)

It was believed that the “Ahrars have lost the little sympathy they ever had by their unreasonable behaviour, and except in the Nationalist section of the Urdu Press, they can find support in no Muslim paper. Indeed, their manifestos are definitely excluded from publication in the two English organs of the community.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 16 November 1931, p. 3)

Chiragh Hassan Hasrat states that “the inquiry commission had been announced, and the Kashmiris seemed to be satisfied to a great extent. When the movement of the Ahrar intensified, the people feared that these agitated youngsters might spoil all the efforts.” (Kashmir, Qaumi Kutub Khana, 1948, p. 165)

Chaudhry Afzal Haq’s statement

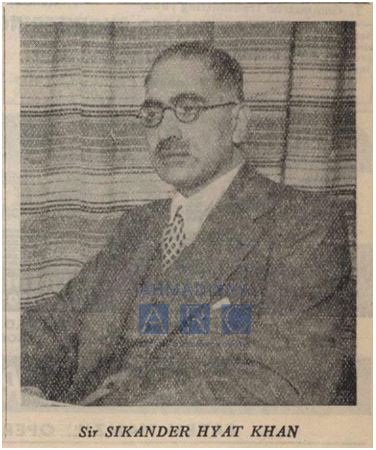

Janbaz Mirza has mentioned that after the appointment of the Glancy Commission, a meeting took place at the house of Sir Sikander Hyat Khan, where Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra was also present. Janbaz Mirza states that Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra “validated the appointment of the Glancy Commission; however, Chaudhry Afzal Haq did not support any decision of the Glancy Commission and declared its appointment to be fruitless for the Kashmiris. On the same day, Sheikh Abdullah accepted the Glancy Commission in his statement issued from Kashmir. After these developments, Ahrar’s civil disobedience took a new turn, and in addition to the Maharaja of Kashmir, this battle began to be fought directly against the Hindu Press, toady Muslims,” Ahmadi Muslims, “and Britain.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, 1975, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, p. 221)

Mentioning the meeting, Chaudhry Afzal Haq states that he addressed Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra and said:

“With the grace of God, we have also made a resolve that we will try our utmost to efface this Jamaat [Ahmadiyyat].” (Tarikh-e-Ahrar, Maktaba-e-Majlis Ahrar-e-Islam Pakistan, 1968, p. 126)

During a speech on 28 December 1944, Huzoorra stated that during the above-mentioned meeting, Chaudhry Afzal Haq said that since Ahmadis did not support him in the elections, “we have made a firm resolve to crush Ahmadiyyat.” Upon this, “I smiled and said that if it was possible for a human to crush Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya, it would have been crushed a long time ago, and even now, if it can really be crushed by a human, it surely does not deserve to live on.” Sir Sikandar tried calming down Afzal Haq; however, he repeated, “I have been disrespected, and now I am determined to crush Ahmadiyyat.” (Al Maud, Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 17, pp. 591-592)

‘Do not threaten us with fire’

During a speech on 27 December 1931, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra said that the Ahrar are “opposing Ahmadiyyat everywhere. One of their leaders has stated that their opposition to Ahmadiyyat holds great benefit for them since they could never achieve fame among the public without it.” Now, “such circumstances have occurred in Punjab that upon witnessing them, one is reminded of the Promised Messiah’sas time. Particularly, the opposition in Sialkot is very serious, and Ahmadis are being made subject to hardships,” and they are threatening to bring mobs to Qadian.

“Our response to them is, ‘What is your significance? If you wish, bring along all the governments and nations of the world and try to overpower us, and if you succeed in your attempt, you would have the right to call us liars.’ If these people made such an attempt, they would come to know what power they were confronting. […] This is a Divine Community and it is His desire and Will to make it successful; no human power can ever do anything against it.” However, “we do not say, ‘We will crush them’, but rather, we say, ‘God will crush them, regardless of how great armies they gather along with them against us. In Islamic terminology, the synonym for the word ‘animosity’ is ‘fire’, and the Promised Messiahas had received a revelation:

آگ سے ہمیں مت ڈرا۔ آگ ہماری غلام بلکہ غلاموں کی غلام ہے۔

“[Do not threaten us with fire, for fire is our servant and indeed, the servant of our servants. (Tadhkirah [English], p. 537)]

“Thus, it is merely their imaginary thought that they could overpower us. Even if they kill us all and then burn us and throw the ashes in the air, Ahmadiyyat will still remain established in the world, spread to every nation and continent, and be seen in all corners of the world. This is a seed that has been planted by God,” and even if all nations joined together, they would be unable to harm Ahmadiyyat. (Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 12, pp. 405-407)

Ahrar’s ‘Anti-Qadian Day’

To express their hate towards Ahmadiyyat, the Ahrar held a series of ‘Anti-Qadian Days’, such as on 17 January 1932. This act of the Ahrar was emphatically condemned by a newspaper, “Rahnuma” of Rawalpindi, on 21 January 1932. The article described their acts as an attempt to harm Muslim unity.

During his Friday Sermon on 22 January 1932, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra advised Ahmadis that though the Ahrar were spreading hate against the Jamaat and fueling the anti-Ahmadiyya sentiments within the Muslim Community, they were required not to fear this opposition and continue to help the oppressed Muslims of Kashmir through prayers and financial sacrifices. (Khutbat-e-Mahmud, Vol. 13, p. 341)

Tabligh: Response to Ahrar’s opposition

During his Friday Sermon on 5 February 1932, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra said that the Ahrar were spreading hate and mischief against Ahmadis and holding public gatherings, where they “used abusive language against the Promised Messiahas and carried out various kinds of mischief.” Ahmadis are required to respond to such acts through tabligh with more zeal, “and to show to the opponents that we cannot abandon the name of the Promised Messiahas with the fear or fright of anyone.” (Khutbat-e-Mahmud, Vol. 13, p. 358)

Kashmiri Muslims were ‘suspicious’ of Ahrar

Gradually, the reality of Ahrar began to unfold. The religious veil was used merely to attract the attention of the Muslim masses; however, the goals were completely political:

“The Ahrars in Lahore” are now “turning to the Congress campaign and initiating civil disobedience. […] These incidents are opening the eyes of all thinking Muslims to what we ourselves have maintained from the beginning, namely, that the so-called Ahrar Muslims were nothing other than a section of Congress, detached to entrap their brethren into the Congress fold. The same tactics, the same slogans, have been evidenced throughout the Maclagan Engineering College dispute, the contest with the Ahmadiyyas at Sialkot, the later phases of the Kashmir campaign and now openly in the civil disobedience movement.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 3 March 1932, p. 2)

“Kashmir’s political and religious circles always remained suspicious of Ahrar’s support or help so they refrained from helping Ahrar emerge as a forceful political party in Kashmir.” (Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2011), p. 99)

According to Ayesha Jalal, “the story of the Congress’s unofficial support of Ahrars in the Punjab for the most part has been kept under wraps. Needing something of a base among Muslims in the province, the Ahrars were an obvious choice.” On the other hand, “having survived the ignominy of being bested by the Ahmadis in the contest for Kashmir, the Ahrars were not prepared to be dictated to by others.” When Sheikh Abdullah formally dissociated himself with the civil disobedience campaign, “the Ahrars charged him for being on the payroll of the Kashmir Committee and, more damagingly, a henchman of the Ahmadis. Refuting the accusations as plainly sinister, the Kashmiri leader maintained that he was proud of being a member of a non-sectarian organization devoted to the welfare of the persecuted.” (Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Routledge, 2000, pp. 361-362)

Chiragh Hassan Hasrat states that the Kashmiri leaders “were very hesitant to cooperate with the Ahrar. It had several multiple reasons. First, the Ahrar had a blemish for being a by-product of the Congress, which was not completely cleaned yet.” On the other hand, the Ahrar “did not respect the young Kashmiri leaders, and insisted that whatever is decided on the issue of Kashmir, must be done after consulting them. Whereas the stance of the young Kashmiri leaders was, ‘If you can help us like the Kashmir Committee is doing, you are most welcome, otherwise, do not interfere in our matters.’” (Kashmir, Qaumi Kutub Khana, 1948, pp. 165-166)

A Kashmiri leader, Sheikh Abdullah, wrote in his book Aatish-e-Chinar that “the All-India Majlis-i-Ahrar saw our misery as a good opportunity to build up their political stature.” (Aatish-e-Chinar, p. 139, Published by Ali Muhammad & Sons, Srinagar)

The Ahrar began spreading rumours about Kashmiri leaders, about which Sheikh Abdullah writes, “In order to put veil on their shortcomings, they gave currency to the story that Sheikh Abdullah has become an Ahmadi,” however, “I had no links at all with Ahmadiyyat in terms of beliefs.” (Ibid, p. 143)

Ahrar agitation was ‘un-Islamic’

It was believed that “the whole Ahrar agitation” was “un-Islamic, and undesirable in the interests of the community. The agitation began, for a purely sectional reason, in order to attack the lead of a sect, with which the Ahrars were not in sympathy.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 7 March 1932, p. 3)

In an interview in Lahore, in 1932, Sheikh Abdullah “paid high tribute to the services rendered to the Kashmir Muslim cause by the Kashmir Muslim Committee and particularly by its president, the head of the Ahmadiyya community of Qadian. As for the Ahrars,” he “considered that the policy of their leaders had been ill-advised and certainly too dictatorial for the Kashmiris, and had done more harm than good.” (Ibid, 11 July 1932, p. 3)

By the end of 1932, witnessing their failure in various attempts to sabotage the peaceful movement for the oppressed Kashmiri Muslims, the Ahrar hatched a vicious plan to initiate a much stronger and dangerous campaign against Ahmadiyyat. Its details will be presented in the second part of the article, insha-Allah.