Ata-ul-Haye Nasir, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat has faced significant persecution in Afghanistan since the early 20th century. During the time of the Promised Messiahas, two of his companions, Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahmanra and Hazrat Sahibzada Abdul Latifra were martyred in Afghanistan. The hostility against the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat continued in the coming years as well.

Persecution in the early 1920s

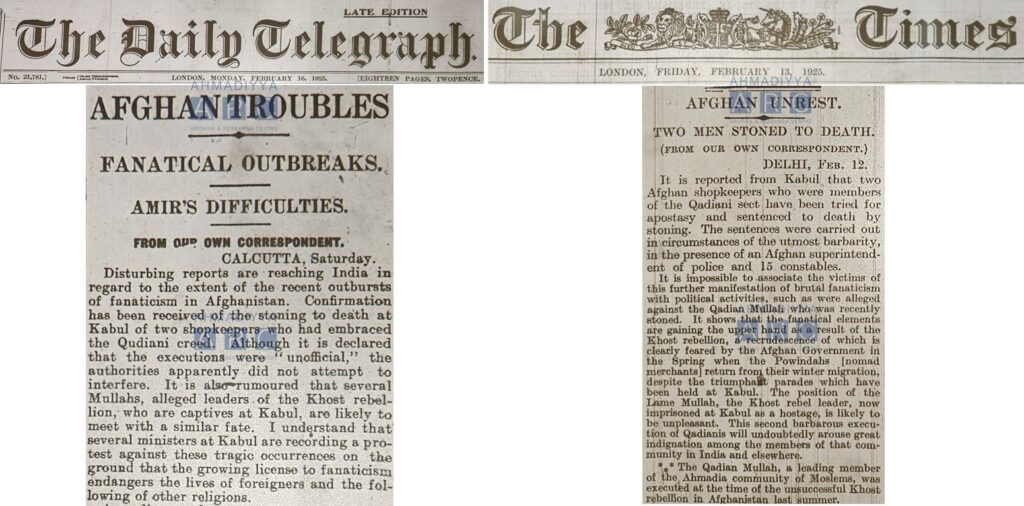

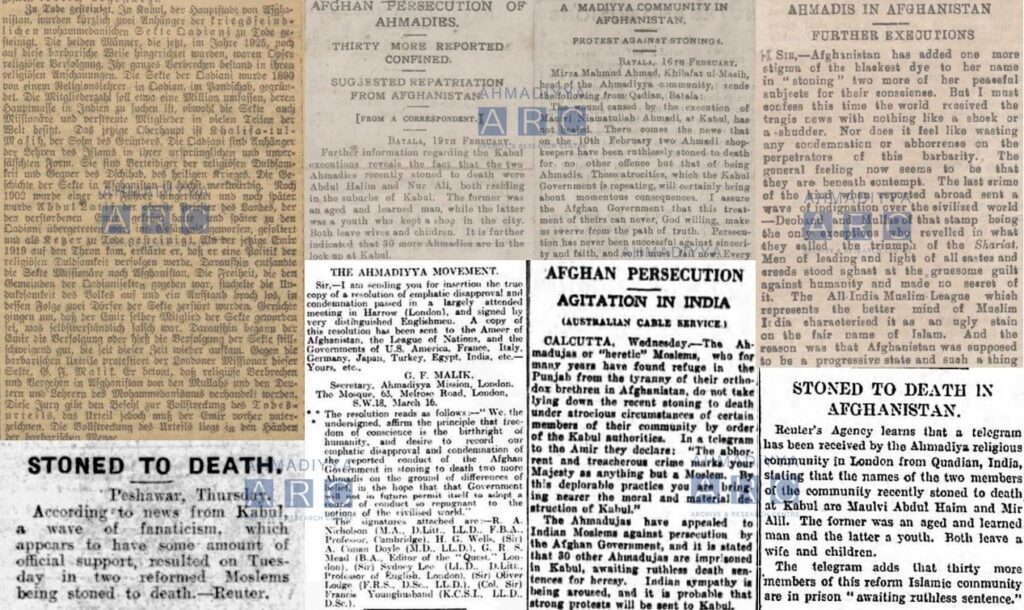

In the early 1920s, anti-Ahmadiyya sentiments were rising in Afghanistan, resulting in the brutal killings of three Ahmadis in 1924-25. It was believed that the prevailing rumours about Amir Amanullah’s conversion to Ahmadiyyat had prompted the “desire of Amir to advertise his orthodoxy.”1 British diplomatic correspondence from this period indicates a complex political landscape, wherein the officials seemed to be somewhat hesitant to protest against these brutalities due to certain diplomatic interests. On the other hand, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya recorded significant protests to raise awareness and, more importantly, to make it clear that such violence did not reflect the true teachings of Islam.

In 1924, while the anti-Ahmadiyya rhetoric was intensifying in Afghanistan, we find an interesting series of correspondence to and fro the Foreign and Political Department of the British Indian Government, wherein the officials enquired about the history of Ahmadiyyat in Afghanistan. A correspondence, dated 3 May 1924, stated, “Many years ago some Afghans Mullahs who came to Qadian in the Punjab, saw the founder of the sect & on return to Afghanistan were killed by a former Amir’s orders – since then the number of followers is said to have increased.”2

This correspondence continued throughout May 1924 and the next month, it was reported by the Military Attaché at the British Legation in Kabul that “an anti-Qadiani sermon” was preached on 20 June 1924. Another correspondence, dated 4 July 1924, mentioned the reports that Amir Amanullah “had started active persecution of Qadianis again to prove the orthodoxy of his own faith.” Another report stated, “Two Mullahs named Abdul Halim and Niamatullah were recently arrested on a charge of being Qadianis.” This was followed by some further correspondence between the officials with reference to a news report of The Bombay Chronicle, dated 14 August 1924, publishing the Jamaat’s appeal for the release of the imprisoned Ahmadis.

After severe torture for a month, Maulvi Abdul Halim Sahib was released, however, Maulvi Nematullah Sahib was stoned to death on 31 August 1924. The opponents’ hostility had reached a strange level, as the NWFP Intelligence Bureau Diary for the week ending on 15 January 1925 reported that “the possession of any photographs of the late Maulvi Niamatullah, Qadiani, has been prohibited in Afghanistan.”3

His Majesty’s Chargé d’Affaires at Kabul mentioned the martyrdom of Nematullah Sahib in a letter dated 2 September and expressed that this action “is evidently due to desire of Amir to advertise his orthodoxy.”4

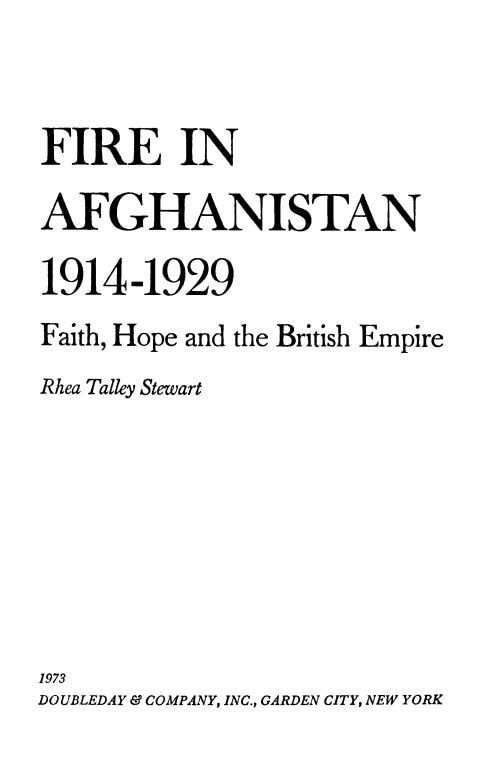

In her book, Fire in Afghanistan: 1914-1929, Rhea Talley Stewart has mentioned the persecution of Ahmadis in Afghanistan and stated that “two members of this sect entered Afghanistan in the summer of 1924, preaching their doctrines, and were arrested by the ecclesiastical courts and charged with heresy.”

She further wrote:

“Maulvi Niamatullah was executed for his beliefs on August 31. And the form of his execution was this: he was led onto an open place at Sherpur, just outside Kabul, and those who attended took up big stones and threw them at him until he was dead. […]

“A week after this stoning Amanullah spoke in the mosque following midday prayers and asked for the denunciation of all Qadianis, who he said would be executed according to law. […]

“In India, whence the Qadianis had come, news of the stoning was a source of distress. The leaders of the Moslem League in India wrote Amanullah a strong letter of protest; Indian newspapers carried such condemnatory articles on the subject that the official Afghan newspaper, the Aman-i-Afghan, felt it necessary to defend both the conviction of Niamatullah and the manner of his execution. […]

“In spite of his public optimism and vigor, Amanullah privately was worried about the future. He issued an order forbidding any more arrests of Qadianis, but there lingered the history of having betrayed his principles.”5

In September 1924, when a certain individual was deputed at the British Legation in Kabul, a person named Jalal Khan Kabuli of Rawalpindi wrote to the Secretary to the Government of India (Foreign Department) that the deputed individual was a “staunch Ahmadi,” and advised to verify it from either “Khalifa Mirza Mahmud Ahmad Qadian” or “Maulvi Mohammed Ali”. He further said, “The appointment of an Ahmadi will be looked upon with feelings of hostility at Kabul, for Ahmadis are considered to be the chief source of mischief there.” He added, “Another way to find out if the man is an Ahmadi is to ask him to pronounce Mirza Ghulam Ahmad a heretic and he would never do it.” Later on, it was concluded by the officials that he was not an Ahmadi.6

The anti-Ahmadiyya sentiments continued to intensify and the clerics were being “appeased” by the government – a fact that was acknowledged (details to be presented later in the article) by the then Afghan Foreign Minister, Sardar Mahmud Tarzi Khan, who was also the father-in-law of Amir Amanullah.

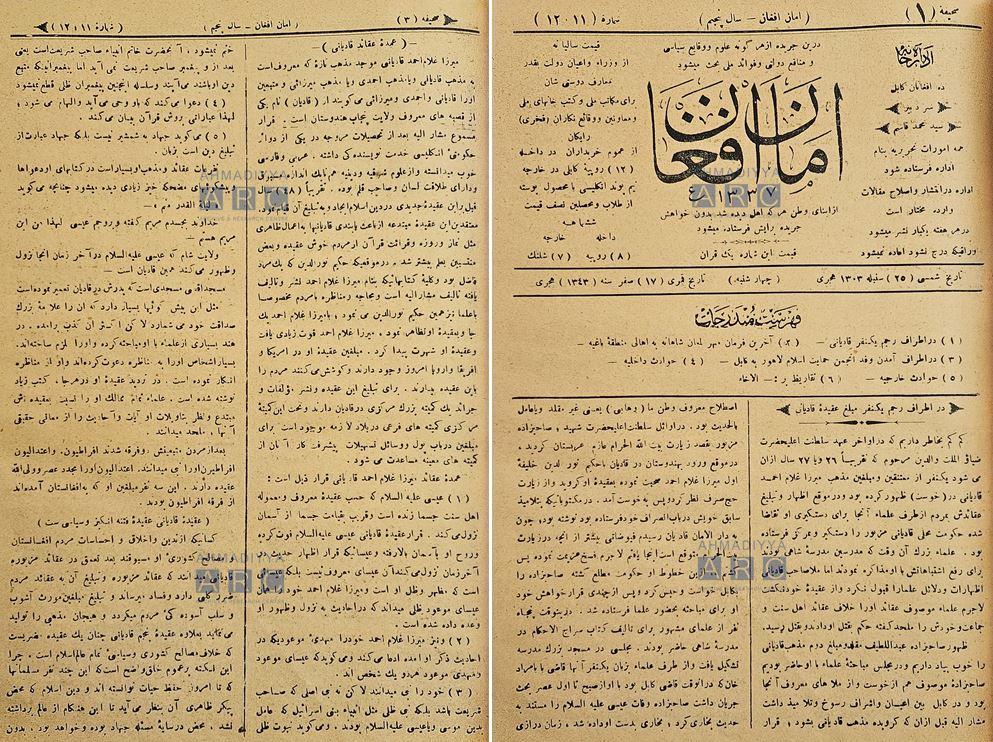

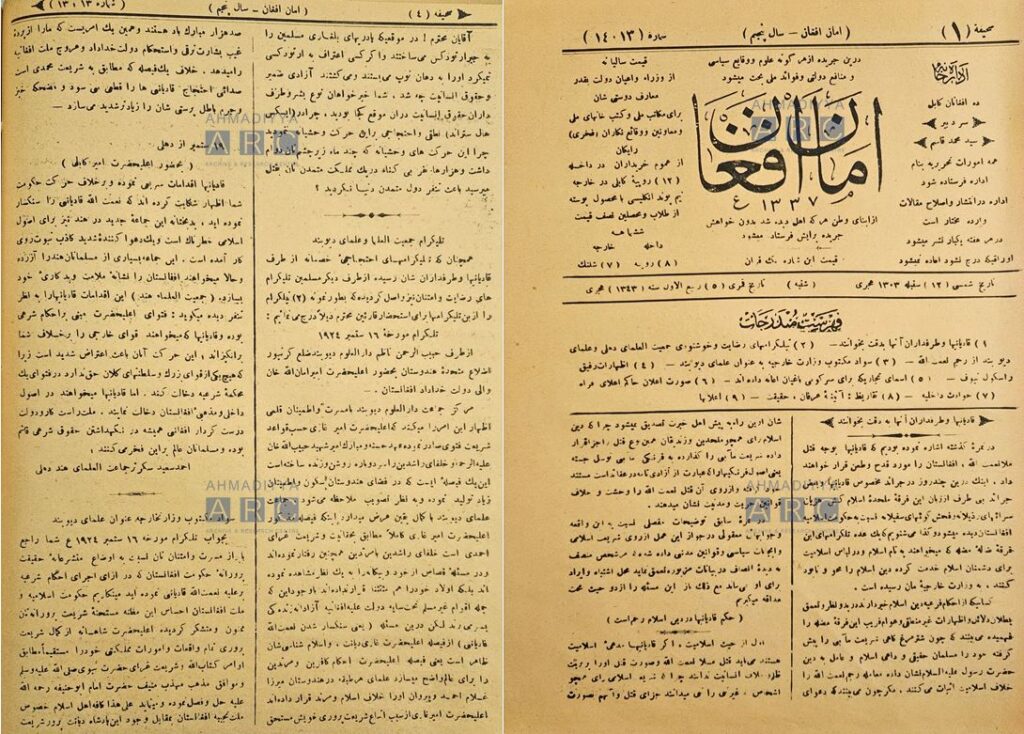

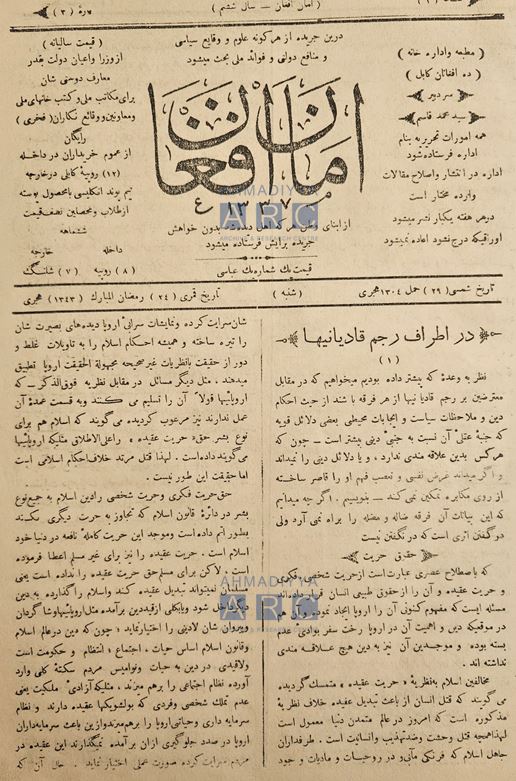

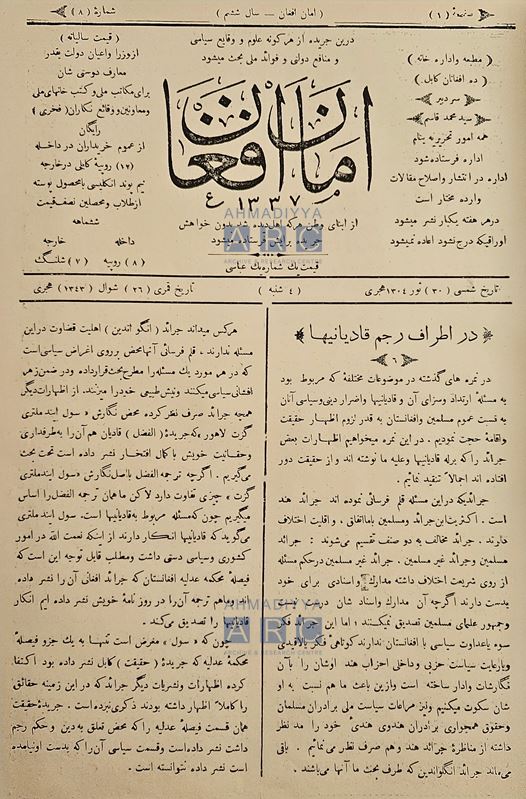

Looking at the Afghan press, we find that a prominent newspaper – Aman-i-Afghan of Kabul – published multiple articles about Ahmadiyyat, as indicated by Rhea Talley Stewart. As for the question of who controlled this newspaper, the statement of Sir F Humphrys – His Britannic Majesty’s Minister at Kabul – would suffice, wherein he wrote to the Indian Government that “it is unfortunately true that Aman-i-Afghan is semi-official organ of Afghan Government. It is controlled by Ministry of Interior.”7

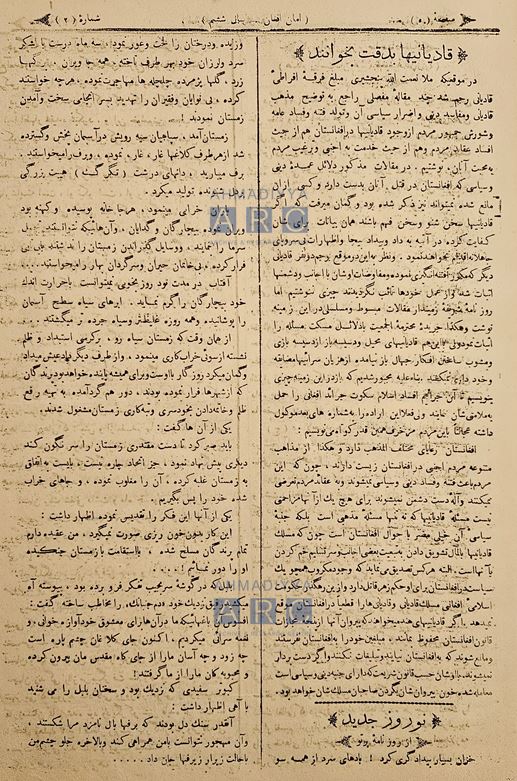

A four-page article featured in Aman-i-Afghan on 17 September 1924 (see above) which mentioned the martyrdom of Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahmanra and narrated some details of the visit of Hazrat Sahibzada Abdul Latifra to Qadian, the bai‘at at the hands of the Promised Messiahas, and the martyrdom when he returned to Afghanistan. After mentioning the martyrdom of Maulvi Nematullah Sahib, the article went on to give a detailed introduction of the Promised Messiah’sas claims.

Another article was published on 4 October 1924 (see below), which mentioned some telegrams from the Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind and scholars of Deoband. While this barbaric act of the Afghan government was receiving open condemnation from various Muslim circles, the above-mentioned telegrams justified it and even congratulated the Amir. This newspaper also published a series of articles following the martyrdoms in 1925; details to follow later in this article.

An extensive account of how the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat reacted to the martyrdom of Maulvi Nematullah Sahib in 1924 has already been published in Al Hakam, so this article will remain focused on the events that followed the martyrdoms in 1925.

The martyrs of 1925

As a result of the state-sponsored hostility, two more Ahmadis were martyred exactly a hundred years ago. Maulvi Abdul Halim Sahib and Qari Nur Ali Sahib were stoned to death on 5 February 1925, just for the sake of their belief in Ahmadiyyat. This atrocity was committed under the Amir’s umbrella, however, he gave the impression as if he had nothing to do with this barbaric act and wanted to convey this sentiment to the West as well.

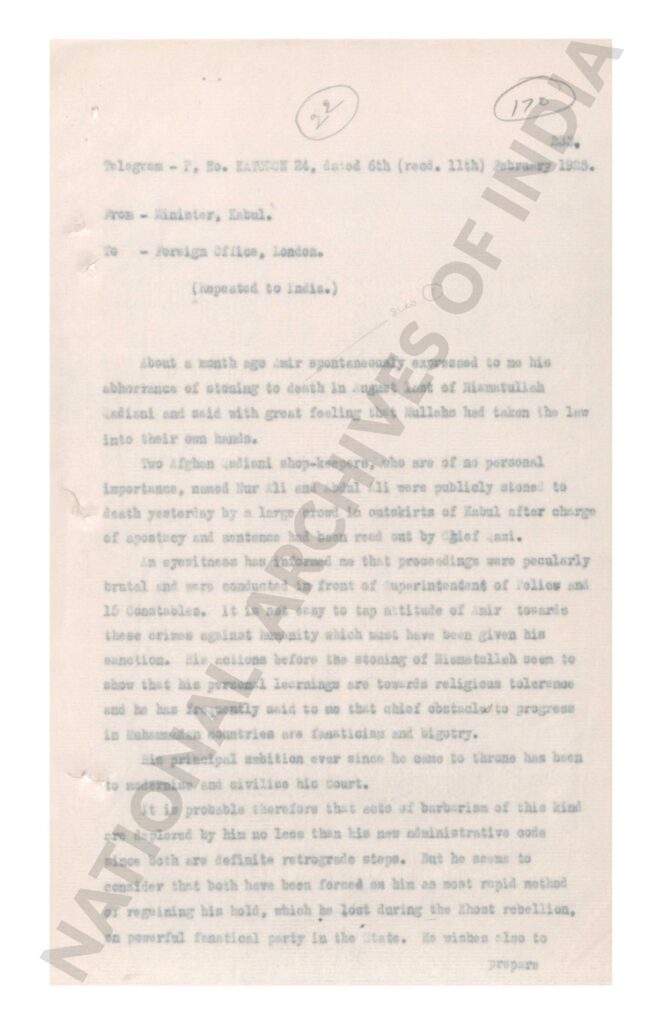

A day after these martyrdoms, Sir Francis Henry Humphrys wrote to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in London (see below), mentioning that a month ago, he had a discussion with the Amir who expressed his abhorrence against the killing of Maulvi Nematullah and “said with great feeling that Mullahs had taken the law into their own hands.” The Minister continued, “Two Afghan Qadiani shop-keepers” were “publicly stoned to death yesterday by a large crowd in outskirts of Kabul after charge of apostasy and sentence had been read out by Chief Qazi.” The Minister expressed his opinion that “it is not easy to tap attitude of Amir towards these crimes against humanity which must have been given his sanction.” A similar telegram was sent to the India Office as well.8

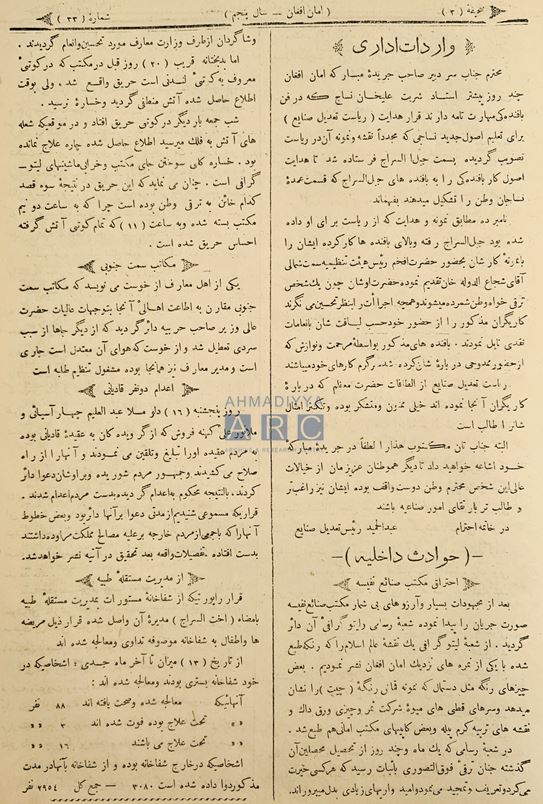

Aman-i-Afghan of Kabul published the news of these barbaric killings in its 9 February 1925 issue (see below). Its English translation, provided to the Indian Government by the Officer Incharge of the Intelligence Branch, NWFP, stated:

“Execution of Two Qadyanis.

“Mulla Abdul Alim [sic., Halim] of Chahar Asia, and Mulla Noor Ali, who sold old things, were the followers of the Qadyani creed. They preached this creed to people and led them astray from the right path. The public was excited and set up a case against them. As a result they were sentenced to death on Thursday the 16th Dalv (5th February) and were put to death by the people. According to what we have heard, a case has long been proceeding against them. Some of their letters, to a number of foreigners with whom they had correspondence, which are against the interests of the country were caught. Details of the matter will be published later, after ascertaining the truth.”9

From the above-quoted letter and news report, one point is clear that it was their belief in Ahmadiyyat and its preaching for which they were sentenced to death and executed. Though Aman-i-Afghan mentioned the alleged political activities, it surely did not present it to be the reason behind their execution. However, in the coming weeks, this newspaper began emphasising the political aspect along with the religious one, though they had no evidence to support this rhetoric. Clearly, it was a desperate attempt to neutralise the backlash received from all over the world.

A file in the India Office Records, titled “Afghanistan: Persecution of Ahmadiyya Sect (P.3607/24)”, manifests that following the martyrdoms in 1925, the British bureaucracy was extremely hesitant in conveying even an informal protest to the Amir of Afghanistan, considering their diplomatic interests and relations. In light of Sir F Humphrys’ suggestion about “an informal demarche”, the officials suggested that it was better “for Sir F. Humphrys to refrain from any comment, however informal.” However, they also expressed that it was “rather repugnant to one’s sense of fitness that the British representative should condone, in any degree, the perpetration of these brutalities under the approval of a Ruler to whom he has recently been delivering messages of personal sympathy from His Majesty the King.” Another point was raised that the “Government of India may be expected to deprecate any comment by Sir F. Humphrys, seeing that in the case of Niamatullah (when there was more direct pressure on us), they ‘considered that it would be dangerous to make any representation, however informal’ (P.4828/24).” Moreover, they feared a “possibility that if Sir F. Humphrys protests to Tarzi, and Tarzi informs the Amir (as he will), the Amir (especially if his conscience is really a little uneasy) may resent the interference.”

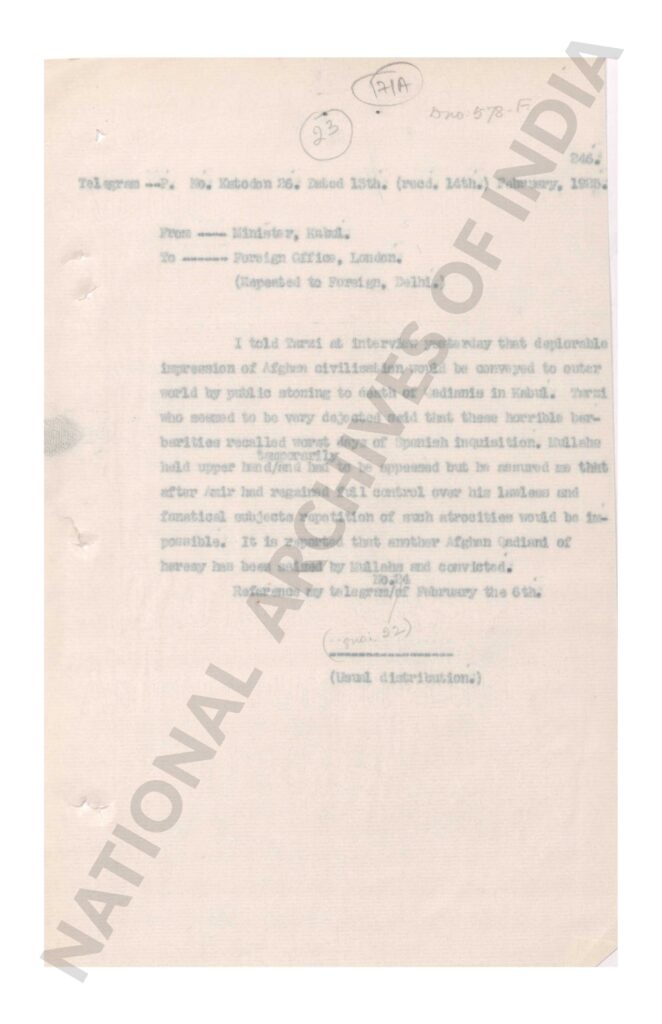

Thereafter, Sir F. Humphrys had a meeting with Sardar Mahmud Tarzi Khan, the then Foreign Minister of Afghanistan and Father-in-law of Amir Amanullah. A telegram to London, dated 13 February 1925, narrated its details. Humphrys told Tarzi that “deplorable impression of Afghan civilisation would be conveyed to outer world by public stoning to death of Qadianis in Kabul.” In response, Tarzi said that the “Mullahs held upper hand temporarily and had to be appeased.” He assured the British Minister that once Amir regained complete control over the country’s situation, such events would be impossible to occur. Concluding the letter, the Minister wrote, “It is reported that another Afghan Qadiani of heresy has been seized by Mullahs and convicted.” A similar telegram was sent to the India Office as well.10

The Ahmadiyya response

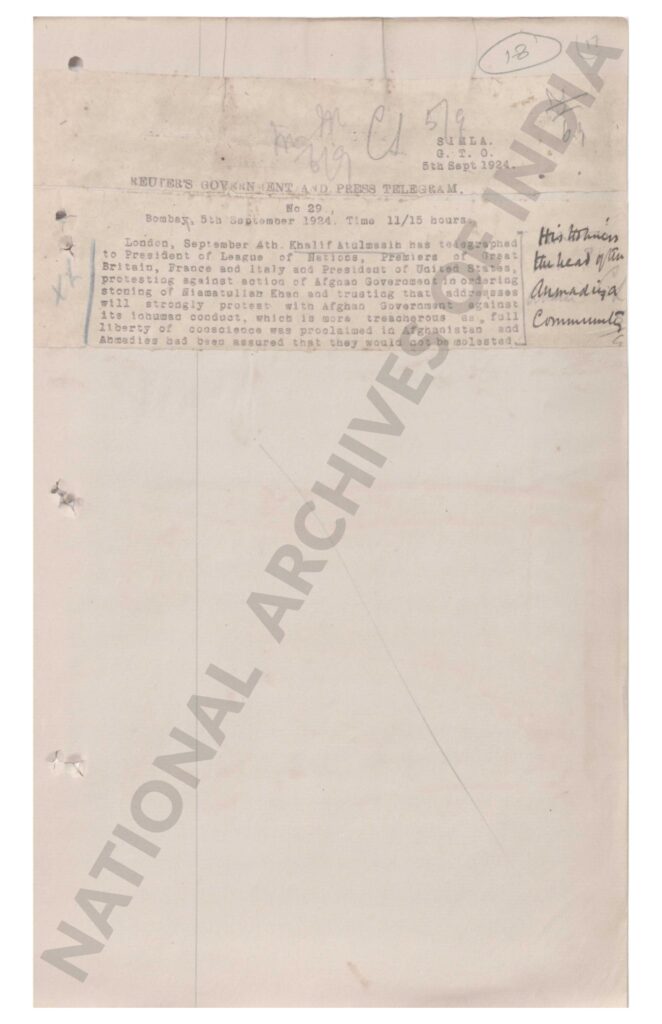

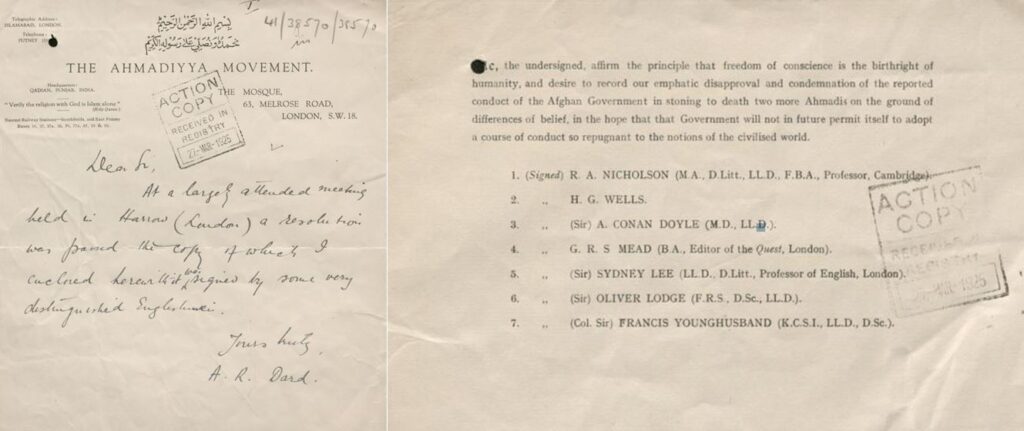

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat’s reaction in 1925 was similar to what had been in the past; patience and prayers amidst persecution and hardships. However, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra also wanted to make the world aware of this barbaric act and to raise awareness. For this, Huzoorra not only sent telegrams to The League of Nations, Viceroy of India and the Secretary of State for India, but also instructed the Ahmadiyya Mission in London to hold a protest meeting to highlight this atrocity. Hence, a protest meeting was held in Harrow, London, at the Greenhill Hall of the Harrow Spiritualist Society. This issue caught the attention of the press from around the world, including England, Scotland, Ceylon, Australia, Canada, America, Hungary and the Netherlands. Its details will be narrated later in this article.

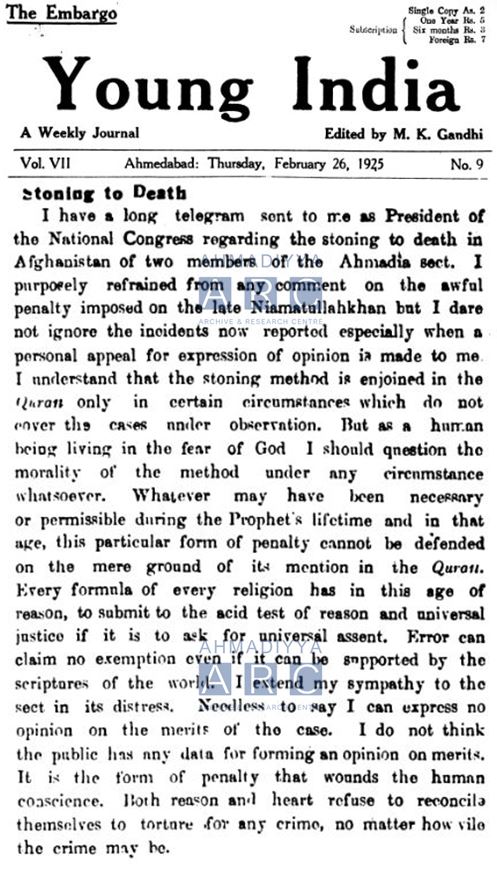

As for the question about the need for such protests and condemnation, it must be noted that these barbaric killings in the name of Islam had provided fuel to the non-Muslims who were already leaving no stone unturned in their anti-Islam rhetoric. It was as if their propaganda of portraying Islam as a violent religion got a new life. On one hand, statements from various prominent non-Muslims leaders, for instance MK Gandhi, attributed false notions to the Holy Quran and Islam in relation to the punishment by stoning to death, on the other, certain Muslim sections commended this barbaric act of the Afghan government and declared that it was in accordance with the Islamic sharia. In such a situation, it becomes clear that the Jamaat’s protest did not aim to harm Islam – as asserted by the Afghan press and certain Muslim leaders – but rather, the objective was to save Islam from the false objections and to highlight the fact that Islam is a peaceful religion and its teaching is against any kind of violence. The need of the time was to clarify that in case of such incidents, Islam cannot be blamed, however, those people must be condemned who have committed such brutality in the name of Islam.

Anyway, when the news reached Qadian, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra delivered a heartfelt speech and emphasised that such oppressions can never halt the progress of a divine community and that the victory always belongs to the Truth (sadaqat). Huzoorra declared that he held no grudge or anger in his heart against the Afghan government in response to its barbaric act. However, Huzoorra declared, “This era will ultimately end, the Amir will also diminish and his helpers and supporters will be gone as well. However, the belief on the basis of which they committed these atrocities shall live on in the world.”

Huzoorra stated that though the opponents of the Promised Messiahas will exist in the world, they will be reduced to a minority, and speaking of that time, Huzoorra advised Ahmadis to never leave morality in the times of majority and power. Huzoorra expressed his hope from the coming generations that upon reading about these atrocities in history, their grudge and passion may not lead them away from morality, just like the Christians drifted away from morality upon gaining power. Huzoorra concluded:

“I advise the coming generations that when God Almighty grants them government and kingdom in return for our humble services, they should not look upon the atrocities of these tyrants, but ought to act with patience as we are enduring now. Moreover, they should not lag behind us in showing morality, but rather, they ought to even surpass us.”11

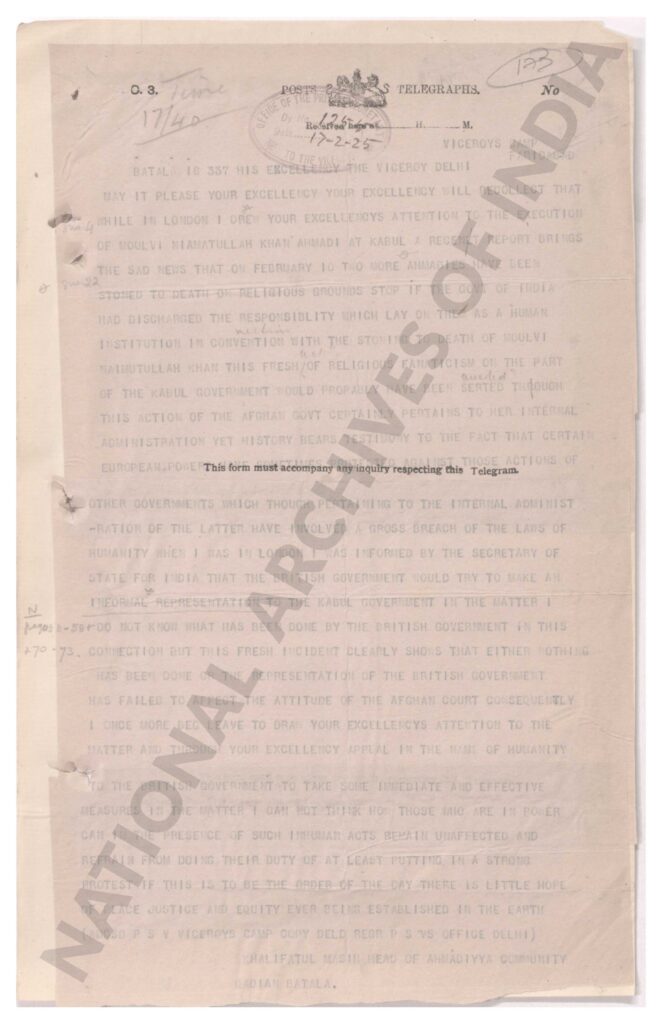

Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra sent a telegram (see below) to the Viceroy of India, informing him about this inhumane act of the Afghan government. It was received by his private secretary office on 17 February 1925.

Another telegram was sent to the Secretary of State for India in London. Later, the Secretary wrote to the Viceroy of India, informing that “Telegram dated 16th February received from Khalifatul Masih appealing for protest to Afghan Government. If you think it desirable he might be informed confidentially of action taken by H.M. Minister [Sir F Humphrys].”

Huzoorra sent a cable to Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahim Dardra – the then incharge of the London Mission – and stated that though these barbaric acts “cannot intimidate us and the result will prove to be the opposite of what the Afghan Government means to achieve, yet such results cannot justify the action of Kabul Government; hence it is our duty as well as that of every lover of freedom of conscience to protest against these outrages.”12

According to an earlier programme, Dard Sahibra was scheduled to visit the Netherlands to deliver lectures in Amsterdam on 19 and 22 February 1925, as he was invited by a society called Vrij Religieuse Tempel. However, after the martyrdoms in Afghanistan, he had to stay in London. So, the martyrdoms caught the attention of the Dutch press as well. For instance, Algemeen Handelsblad of 19 February 1925, mentioned that Dard Sahibra had to stay in London due to the martyrdom of two Ahmadis in Afghanistan. The same periodical mentioned this postponement in its 24 February 1925 issue, along with an introduction to Ahmadiyyat and claims of the Promised Messiahas, originally published in De Tempel.

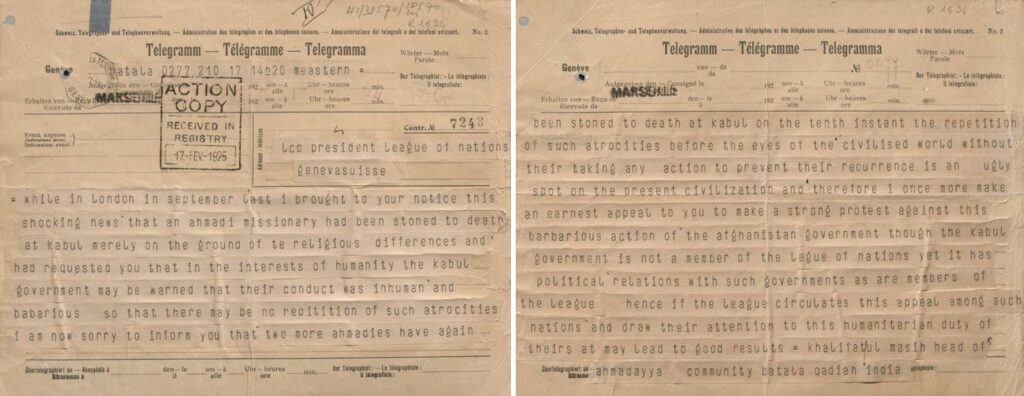

Huzoorra sent a telegram to The League of Nations as well (see below). An acknowledgement was received on 18 February which stated, “The Secretary General of the League of Nations has the honour to acknowledge the receipt of a telegram, dated February 17th, from the Head of the Ahmadyya Community at Batala, concerning the execution of two Ahmadies at Kabul.”

According to The Evening Star of Washington D.C., dated 20 February 1925, “The League of Nations received a communication” from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, “protesting against the execution of ‘two more members of their community’ at Kabul by order of the government. The community appeals to the league for intervention. The secretariat turned over the matter to the section for protection of minorities, under which it falls.”

The same news was published by The Montreal Star of Canada, on the same day. The Sun of Sydney, Australia, also wrote on this subject in its 21 February 1925 issue.

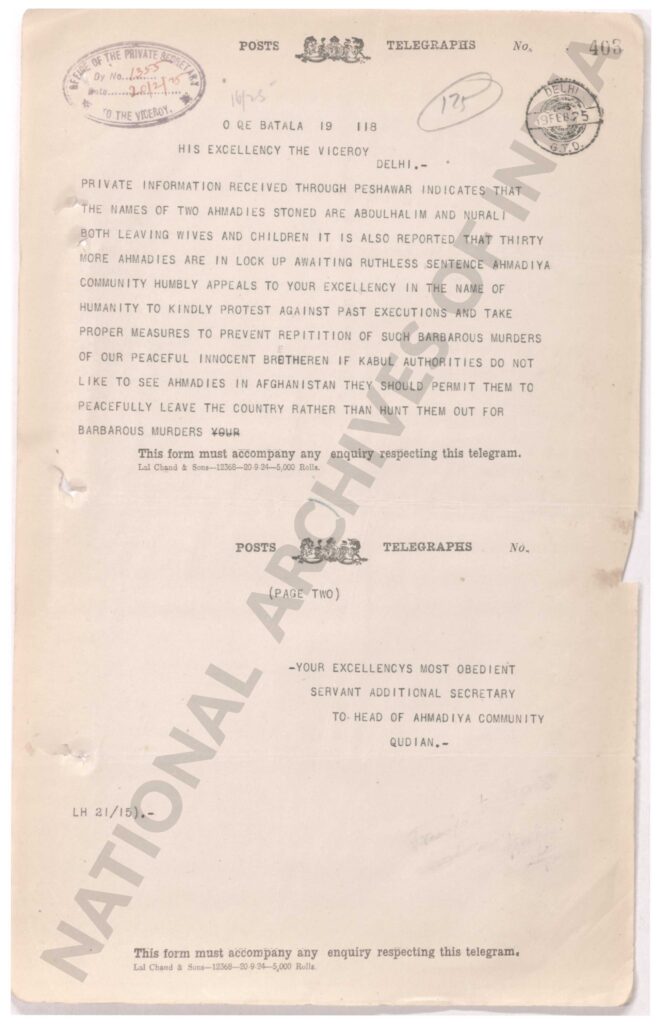

Upon the direction of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, a telegram was sent to the Viceroy of India, wherein it was stated that according to some private information received through Peshawar, the two martyrs in Kabul were Maulvi Abdul Halim Sahib and Nur Ali Sahib, and that 30 more Ahmadis in lock-up there were awaiting a ruthless sentence.

This cable was quoted by a prominent British newspaper, The Manchester Guardian, under the heading “Stoned to Death in Afghanistan”, on 23 February 1925.

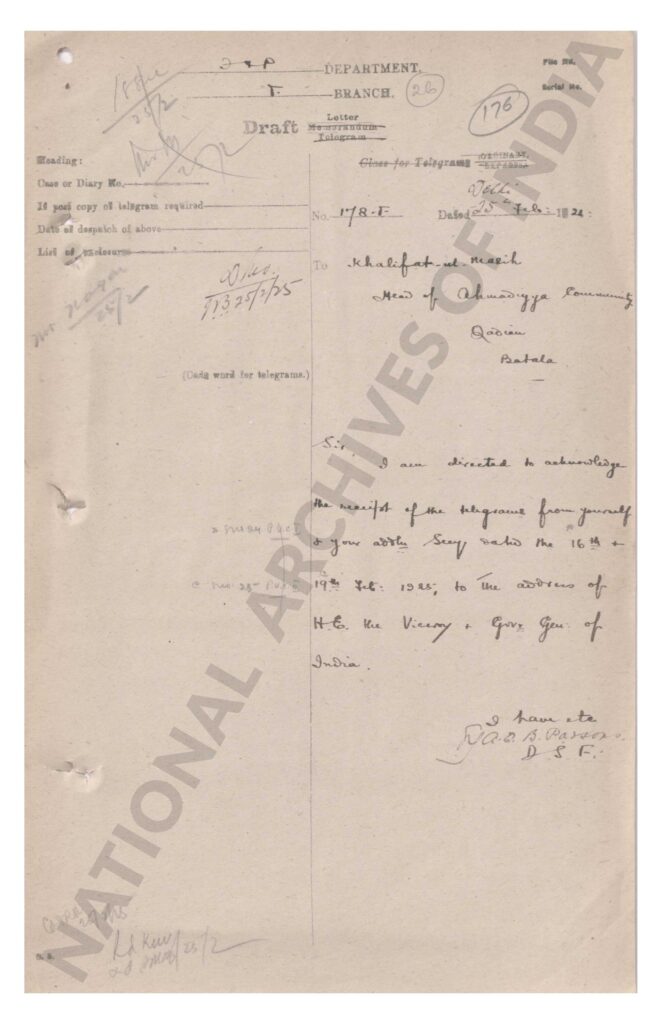

An acknowledgment from the Viceroy’s office was received on 25 February 1925, stating:

“To,

“Khalifatul Masih, Head of Ahmadiyya Community

“Qadian, Batala

“Sir

“I am directed to acknowledge the receipt of the telegram from yourself & your addit. Secy. dated the 16th and 19th Feb. 1925, to the address of H.E. the Viceroy & Gov. Gen. of India.”

Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra sent the latest information to the London Mission as well, where Hazrat Malik Ghulam Faridra had already sent a letter to The League of Nations on 13 February; its acknowledgement was received on 17 February. He quoted an excerpt from The Times of 13 February 1925 that reported on this barbaric act. He informed The League of Nations, “As it forms a continuous series of barbarous and atrocious murders the representatives of the Ahmadiyya Community in London think of holding again a meeting of protest to condemn this recent outrageous act of the Afghan Government.”

The protest meeting in London

The Spalding Guardian reported on 21 February 1925 that the “Ahmadiya Moslems in London propose to hold a meeting of protest against the stoning to death after a trial for apostasy of two members of the Ahmadiya community in Kabul.”

Thereafter, the protest meeting was held in Harrow, London; wherein a resolution was passed and its copies were sent to The League of Nations, the Amir of Afghanistan, the Viceroy and Governor General of India, and press around the world. The signatories included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sir Francis Younghusband. An acknowledgement was received on 28 March 1925.

The Yorkshire Post, dated 24 March 1925, published the correspondence received from Hazrat Malik Ghulam Faridra about the resolution.

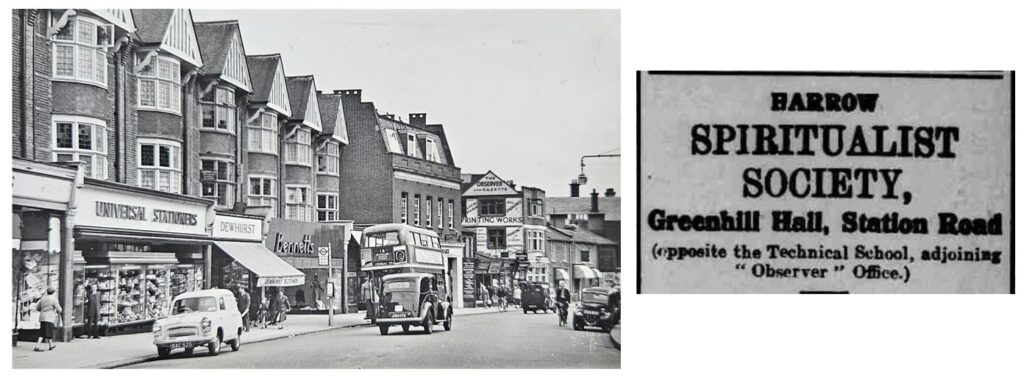

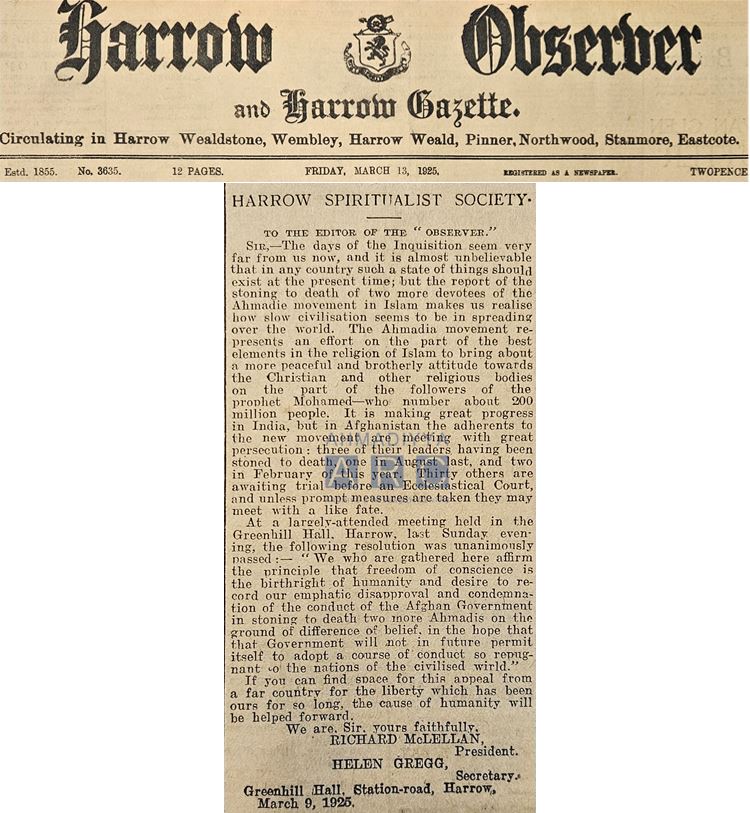

We learn from the Harrow Observer and Harrow Gazette (see below) that this protest meeting was held at the Greenhill Hall of the Harrow Spiritualist Society, on Sunday, 8 March 1925. This hall was located at “325 Station Road, HA1 2AA”.

The President of this Society expressed his impressions about the martyrdoms and the protest meeting in his letter to the Harrow Observer, that was published on 13 March 1925. He stated:

“The Ahmadia movement represents an effort on the part of the best elements in the religion of Islam to bring about a more peaceful and brotherly attitude towards the Christian and other religious bodies on the part of the followers of the prophet Mohamed[sa]” and it is “making great progress in India, but in Afghanistan the adherents to the new movement are meeting with great persecution: three of their leaders having been stoned to death, one in August last, and two in February of this year.”

Mentioning the protest meeting, he wrote:

“At a largely-attended meeting held in the Greenhill Hall, Harrow, last Sunday evening,” a “resolution was unanimously passed.”

After quoting the resolution, he stated:

“If you can find space for this appeal from a far country for the liberty which has been ours for so long, the cause of humanity will be helped forward.

“We are, Sir, yours faithfully,

“Richard McLellan, President,

“Helen Gregg, Secretary,

“Greenhill Hall, Station-road, Harrow

“March 9, 1925.”

A newspaper of Budapest, Hungary, also published an article that mentioned the martyrs and gave an introduction of the Promised Messiahas, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra and Hazrat Sahibzada Abdul Latifra Shaheed. It also mentioned that “the London missionary of this sect, G. F. Malik, protested against the barbaric sentences.” (Pester Lloyd, 13 March 1925, p. 5)

Other newspapers which reported on this subject, included The Leicester Mail (12 February 1925), South Wales Daily Post (12 February 1925), Evening Despatch (12 February 1925), Edinburgh Evening News (13 February 1925), The Telegraph (16 February 1925), The Pioneer Mail and Indian Weekly News (20 and 27 February 1925), The Manchester Guardian (21 February 1925), The Times of Ceylon (5 March 1925) and The San Francisco Examiner (8 March 1925).

The Civil and Military Gazette of Lahore published a lengthy article, titled “The Kabul Executions” and stated:

“The barbarous execution of two humble Qadiani Afghan shopkeepers at Kabul has aroused feelings of horror in India and it will, no doubt, be the subject of severe comment in other countries besides. When a few months ago, the news reached India of the stoning to death of the Qadiani Niamatullah, it was accompanied by hints that the victim had been involved in a conspiracy against the Afghan Government! This was strenuously denied by the Community to which he belonged and it may be noted that the Afghan newspapers themselves did not hesitate to confirm those denials by publishing the judgment of the Court which tried him, a translation of which was reproduced in our columns. Whatever may have been his alleged offence, the terribly brutal character of the punishment inflicted received general condemnation.”13

We also learn that during a session of the U.P. Muslim League, a telegram from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat was read out which mentioned the Kabul martyrs and urged the Muslim community of British India to condemn this barbaric act of the Afghan government. It was demanded that “something practical should be done to make the Afghan Government realise that the outside Muslim world condemn these atrocities of the Kabul Court and asking the President to send a strong protest to the Amir on behalf of the Muslim community.”14

The Daily Mail of Brisbane, Australia, dated 27 February 1925, wrote that “in a telegram to the Amir,” the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community “declare: ‘The abhorrent and treacherous crime marks your Majesty as anything but a Moslem. By this deplorable practice you are bringing nearer the moral and material destruction of Kabul.’

“The [Ahmadis] have appealed to Indian Moslems against persecution by the Afghan Government, and it is stated that 30 other [Ahmadis] are imprisoned in Kabul, awaiting ruthless death sentences for heresy. Indian sympathy is being aroused, and it is probable that strong protests will be sent to Kabul.”

The martyrdom of Ahmadis in Afghanistan came under discussion during a session of the Central Legislative Assembly of India as well, where a member presented some questions in regard to this incident, asking for more elaboration on this.15

Aman-i-Afghan’s ‘violent articles’

The Aman-i-Afghan of Kabul was trying to neutralise the protest and condemnation – emerging through the worldwide press – against this barbaric act of the Afghan government. In an article, dated 9 April 1925, it was reiterated that the two Ahmadi martyrs were indulged in political activities against the country, though without any evidence. Two British Indian periodicals, Zamindar and Al Jami‘at were also commended for their articles. Maulvi Zafar Ali Khan’s Zamindar published multiple articles, justifying the killing of Ahmadis in Afghanistan by declaring them apostates.

In this article, it was stated:

“The Islamic Government of Afghanistan does not at all give room to the Qadyani creed and the Qadyanis in Afghanistan. If the Qadyanis of India desire that their followers should remain immune from the grip of Afghanistan’s Penal Law, they should not send their preachers to Afghanistan and should prevent them from coming to, and preaching in, Afghanistan. If they do not abstain they will be treated according to the Shari’at law, which has both the religious and political sides. Those of them who hold the policy will be responsible for the blood-shed of their followers!”16

On the other hand, the Zamindar of 16 April 1925 alleged that a large number of Ahmadis were employed at the British Legation in Kabul. Zamindar wrote that it was feared that the British Legation in Kabul became the centre for rendering secret help to the Ahmadis. It further mentioned that certain prominent Englishmen have also adopted a resolution disapproving of the stoning of some Ahmadis to death in Kabul. The British Government should restrain Englishmen from such reckless doings, otherwise its relations with Afghanistan will become strained. It should not interfere in the internal affairs of Afghanistan.17

Zamindar’s aim was just to fuel the anti-Ahmadiyya sentiments which were already growing in Afghanistan, as evident from the barbaric killings of Ahmadis.

Upon such statements, the Indian Government asked Sir F Humphrys, “Can we state that no Ahmadis are employed and do you think it advisable to issue contradiction?” The response was, “No Ahmadis are employed in Legation. I consider in view of offensive articles in Aman-i-Afghan” that “it would be advisable to publish contradiction.”18

Hence, the Indian Government instructed Zamindar to publish a correction, which was published in its 28 May 1925 issue, which read:

“In our issue of April 16th we wrote in the course of a leader headed ‘Incurable sore on the body of Islam’ as follows:

“‘We learn from some source that there is a preponderating majority of Qadianis at the British Legation, Kabul. If this report is correct, our fears are not groundless.’

“We learn now that the above report is not true.”19

Aman-i-Afghan published a series of articles, titled در اطراف رجم قادیانیھا (literally, “Regarding the stoning of Qadianis”), implying that Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya was presenting incorrect information about this incident.

The first part of this series, dated 17 April 1925, stated that they aimed to write a response to the protests expressed against the stoning to death of these two Ahmadis.

The third part stated, “In Afghanistan also the Ulema, like the Ulema of other Islamic Countries, have declared the Qadyanis to be heretics and they demand their execution at the hands of the Government. The Government of Afghanistan, being an independent Islamic Government, considers the Ulema’s Fatwa worthy of execution. The agitation of a number of the enemies of Islam cannot prevent it from carrying out the commands of its religion.”20

After the third part, Sir F Humphrys wrote to the Foreign and Political Department of the Indian Government and sent details of the “violent articles that have been appearing lately in the ‘Aman-i-Afghan’ on the subject of Qadianis.” He added, the Afghan Foreign Minister, “Mahmud Tarzi recently told me that he dissociated himself absolutely from the sentiments expressed in these articles, and I gather that the Amir has felt obliged to publish them as a sop to the fanatical party.”21

It was expressed in another correspondence that “the arguments ring hollow, and the clumsy attempt to associate the Qadiani creed with political intrigue and sedition is lacking in conviction.”22

Aman-i-Afghan stated in the fourth part that Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya had, God forbid, corrupted the religion of Islam and that they portrayed themselves as Muslims and helpers of Islam, however, on the contrary, they served the enemies of Islam.

The sixth part began with the following statement:

“In the previous issues, we have discussed various topics related to the issue of apostasy and its punishment, the Qadianis and their religious and political harm to the general Muslim community and Afghanistan, as much as necessary to state the truth and establish evidence. In this issue, we would like to briefly criticise the statements of some newspapers that have written about the Qadianis and against us, and which have strayed far from the truth.”23

Aman-i-Afghan criticised all those periodicals which highlighted the protest raised by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat against this barbaric act, and it was asserted that the Anglo-Indian newspapers were unaware of the true facts and circumstances. Aman-i-Afghan’s above-mentioned article was discussed in The Civil and Military Gazette’s 2 July 1925 issue as it implied that this Indian newspaper was spreading incorrect notions and supporting the Ahmadiyya view on this incident. Aman-i-Afghan commended those Muslim leaders, periodicals and organisations which spoke against the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat. It particularly commended, once again, Maulvi Zafar Ali Khan and the editorial staff of the Al Jami’at.

The National Archives of India holds the record of various telegrams that were sent to the authorities, including the Viceroy of India, by various chapters of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, to record their protest against these barbaric killings. These chapters included Ceylon, Karachi, Kerang, Sambrial, Burma, Malabar, Multan and Calcutta.24

Conclusion

The history of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat testifies that the opposition could never halt its progress; rather, it has always proved to be fruitful. The most influential newspaper of Afghanistan, controlled by the Afghan Ministry of Interior, served as a means to spread the claims of the Promised Messiahas – though its articles incorporated particular perspectives pertaining to the Ahmadiyya beliefs which were based on the editor’s own comprehension or convictions. It surely testified to the Promised Messiah’sas statement where he said that “my opponents are actually my servants and helpers, because they convey my message to the east and to the west.”25

Endnotes:

- National Archives of India (NAI), Government of India: Foreign and Political Department, File No. 60/11-E

- Ibid., File No. 178-F

- Ibid.

- Ibid., File No. 60/11-E

- Fire in Afghanistan – 1914-1929: Faith, Hope and the British Empire, 1973, New York, pp. 280-282

- NAI, Government of India: Foreign and Political Department, File No. 60/11-E

- Ibid., File No. 579-F

- Ibid., File No. 178-F

- Ibid., Translations of extracts from Afghan newspapers for the year 1925, File No. 187/1-F

- Ibid., File No. 178-F

- Al Fazl, 19 February 1925, p. 7

- The Review of Religions, March 1925, p. 3

- The Civil and Military Gazette, 17 February 1925, p. 5

- Ibid., 26 February 1925, p. 11

- NAI, Foreign and Political Department, File No. 31/35-F

- Ibid., Translations of extracts from Afghan newspapers for the year 1925, File No. 187/1-F

- Ibid., Government of India: Foreign and Political Department, File No. 579-F

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- NAI, Translations of extracts from Afghan newspapers for the year 1925, File No. 187/1-F

- Ibid., Government of India: Foreign and Political Department, File No. 579-F

- Ibid.

- Aman-i-Afghan, 20 May 1925, p. 1

- NAI, Government of India: Foreign and Political Department (Frontier), File No. 178-F

- Malfuzat [English], Vol. 2, p. 112