Asif M Basit, Curator, Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

The span between the rise of Islam and as-Sa‘ah

How much time would span between the advent of Islam and the as-Sa‘ah – the Quranic term for the Day of Judgment – always remained unclear. The Holy Prophetsa of Islam repeatedly spoke of the advent of the Messiah and Mahdi as a sign of as-Sa‘ah but expressed his unawareness as to its exact timing. He is said to have asked some prophets – in a vision – the same question, only to have received the same reply as his own. This vision, however, gave him another clue that the second advent of Jesussa would be a harbinger of as-Sa‘ah.

Reading through the voluminous narrations of his companions, it appears that contemplating and reflecting on this question was a favourite topic and the as-Sa‘ah was usually perceived as lurking on the near horizons. This anticipation continued for decades and then centuries, but doomsday, as these lines are being written, has not struck. However, it remains a sad fact that Islam was struck with various other forms of doom and destruction in the meanwhile.

Sectarian divide

Even a not-too-detailed study of the ahadith (sing. hadith) sufficiently reveals that the Holy Prophetsa understood it to be centuries apart from his time. Had it not been so, he would not have mentioned the mujaddidun (reformers) to appear at the turn of every “century”. Also, if his ummah was to split into seventy-three sects, this too could not have happened over a few years or even decades – a phenomenon that he saw as a parallel to the Jewish nation. This too would have required centuries to transpire, and we now know that it did. History tells us that such scholastic differences and the subsequent schisms evolve over hundreds of years.

During this long stretch of time that has fallen between the time of the Holy Prophetsa and the yet-awaited as-Sa‘ah, his traditions were compiled through various phases. These collections resulted in an understanding of his sunnah (practices), which consequently led to the formation of schools of fiqh and also opened up new avenues for interpreting the text of the Holy Quran.

This prophesied schism, thus, took birth in the very early centuries of Islam, and at a time when the neighbouring, mighty Byzantine scholarship was undergoing a revival of Hellenistic philosophy. For any religious debate with them, an equal level of understanding of philosophical debate was required. Thus, philosophical polemics seeped through the walls of Islamic theology.

The European Renaissance

Philosophical debate and scientific investigation flourished in direct proportion, while religion faced an inverse trend. It took several centuries for Europe to enter the phase that is now referred to as the Age of Renaissance – where religious dogma came under strict scrutiny at the hands of scientific inquiry and philosophical awakening. Although Christianity remained the main target, religion suffered a setback as a whole.

The scepticism that pumped blood into the Renaissance had developed as a reaction to European monarchs who, claiming to be divinely anointed and appointed, would exploit the general masses in every possible way. Christianity began to be seen as a twin of economic exploitation and hence, the aversion and loathing for the latter automatically meant rejecting the former, as both fuelled mutual interests.

The European mind, having distanced itself from religion, entered the Age of Enlightenment – ironically so named to express repugnance for the term’s religious bases, and an inclination towards scientific/rational belief. This age saw the onset and rise of atheistic and agnostic tendencies that reached their apex in what is called the Modern Age.

Religion was painted as a nonentity or, more so, as a lethally poisonous entity for human society. Karl Marx summed this up in his famous dictum (1843), stating that religion is “the opium of the people”, used (or abused, if Marx is to be truly represented) to cool off any questions that might be sizzling in the general public’s mind.

In just a matter of years, this gust of disbelief had picked up so much momentum and pace that Nietzsche shouted aloud his bold slogan: “God is dead!” (1882).

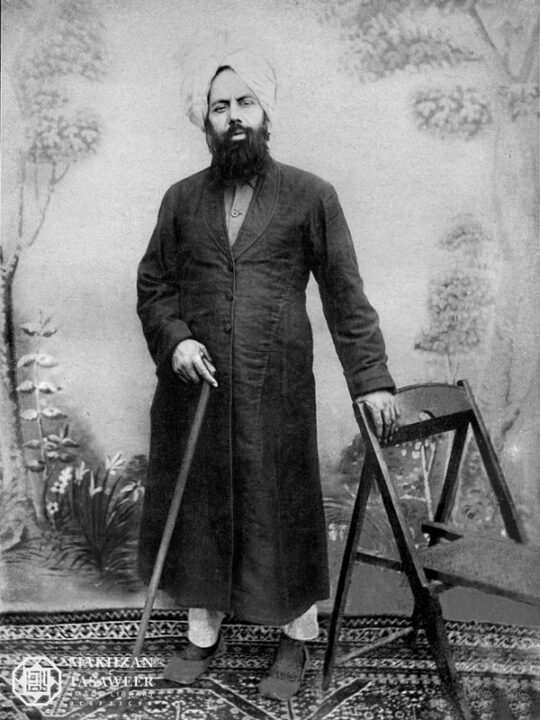

These two dicta of Western philosophy are representative of its spiteful aversion to religion. Chronologically speaking, the former emerged around the time of the birth of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian (1835), the latter around the publication of his work Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya.

A joint venture of politics and economics

What must remain before the reader is that the roots of these philosophical movements ran deep into the cycle of politics and economics, better referred to as political-economics, where both fed off each other. Where the Christian monarchical system had led people away from religion, poverty remained at the heart of their social problems. People had generally grown weary of being exploited by their feudal masters, who, with the Industrial Revolution, had become owners of factories and mills and hence their employers. Members of the general public still remained instruments in the machines that churned out and produced wealth for the elite class.

Revolting against the rulers and the elite establishment became fashionable. Industrialisation of the economy had brought about a certain level of economic ease, but in this process, machines had turned Man into mere labour – a working-class devoid of happiness and joy.

Where this contentment was lost remained beyond the working-class majority’s understanding and in its futile pursuit of happiness, God never occurred as a possibility to a collective psyche that had thrust away its faith in religion with much disgust.

Happiness was thus sought through a reactionary indulgence in materialistic joy and bodily pleasure, with the soul being nowhere in the equation. It is the same liberalist and individualistic tendency, albeit at its worst, that we see the West embracing today – in a world where the West is what dominates the entire globe.

Freedom of expression and liberalism

The Man of the industrial age had embarked upon a pursuit of his lost self but ended up embroiled in the roaring wave of individualism. I am who I am and I can do what I want, when I want. I can wear what I want (if I want to); do what I want, where I want. Such were the lines along which lay his reactionary response to the existential question. Modern Man revolted against any religious, social, ethical, or even political restriction and took pride in this newfound sense of freedom and liberty.

This happened at a point in history when existentialism had started to blossom and modern Man had crossed the threshold of Modernism and stepped into the wave of post-modernism. This turning point swept away the need for any religious, political or ethical affiliation – all pulled into the big black hole that had once devoured religion.

Chronologically speaking, all this happened around the time of the foundation of the Ahmadiyya community – the end of the nineteenth century.

As tides of irreligiousness washed the shores of human society with a never-before-seen vigour, religion struggled to find its feet, trying not to let the sand slip away from beneath them. The church was active and Isaac Newton can be seen as their stalwart who, despite being a very influential scientist, remained a devout Christian and worked to prove that science and religion were harmonious and not repulsive forces. Descartes, with his impressive mark on Western philosophy, too remained a Christian and tried to reconcile the two.

This effort to harmonise science and religion remained at the heart of the Renaissance as well as the age of Enlightenment. Universities like Oxford and Cambridge – now the bedrock of liberalism – were initially founded with the same goal, as the names of their affiliated colleges suggest: Jesus College, Trinity Christ Church, Magdalen College and Trinity College, etc.

Religion in the Age of Colonialism

By this time, European powers had gotten busy colonising other regions of the world. Christian mission societies, seeing their own continent becoming infertile for faith, headed to the colonies – or heathen lands, as they would call them – to win converts and thus resuscitate Christendom through propagating Christianity.

So organised were these societies that no other religion in the world could beat their resolute and concerted structure. Their mutual disagreements and schisms aside, a Catholic mission society was fully sponsored by the Vatican, and a Protestant one by the mighty Church of England. The huge funding required for such expansive ventures also came from the same powerhouses. Such societies, wherever they established themselves, would not only preach their faith but also establish schools and clinics for the natives. Such societies take credit, and rightly so, for introducing women’s education through their zenana schools in most colonial lands.

Where the teacher, the healer and the provider of life’s amenities – all three being otherwise scarce – were all Christians, the desired outcome of mass conversions became easily achievable. Adding further ease was the attraction of a religion that drew no lines of caste or creed – a system that had crushed the low-caste Hindus within their own faith.

For Muslims, weighing up between a dead prophet and Christ, who was alive – as the missionaries presented the case – was a major factor in making the choice natural and easier. Karl Pfander proudly boasted this parallel in his book Mizan al-Haq and provided missionaries with an efficient weapon to secure mass conversions from among the Muslims.

Leaders of certain factions of Hinduism took on the Christian challenge through proselytising, something that had thus far remained alien to the Hindu faith. The likes of Brahmu Samaj did not resort to proselytising but allowed converts into the fold of Hinduism – again, thus far a non-possibility. Tweaking the tenets of faith was also witnessed among Hindus, an example of which can be seen in a shift from their belief from polytheism to monotheism in the case of Brahmu Samaj.

This was happening at a time when the Promised Messiahas was working at the Sialkot courts as a deputy sheriff. He would spend his leisure time in polemical discourse with Christian missionaries. This post-mutiny era of the mid-19th century was an immensely challenging time for the religious climate of India, and Christianity emerged as a champion.

The mutiny of 1857 had produced a pollen of questions, dispersed all over the Indian Subcontinent by the winds of scepticism. The particle of this pollen that germinated best among the Muslims was the question of foreign rule – foreign in both the political and religious senses of the term. Did the British occupation of India make her Dar al-Harb or did she remain Dar al-Islam? (The former calling for Jihad, the latter otherwise.)

This issue, which called for interpreting Quranic verses and ahadith on such, or similar topics, was addressed by leaders of almost all Islamic sects. This exercise resulted in further divide amongst Muslims and the Holy Quran became heavily disputed like never before. Various verses got to be seen as mansukh (abrogated) and others as their nasikh (that abrogated the former).

Practically and realistically speaking, Muslim scholars took it upon themselves to edit the Word of God. This, for the general Muslim public, meant that if certain verses of the Holy Quran could be declared abrogated and, hence, invalid for our day and age, what else could there be in the text that called for revision? Such a sceptic view towards the Holy Quran, the core of the Islamic faith, led to the possibility of Islam’s edifice falling apart.

Where fundamentalist and orthodox scholars of Indian Muslims – the likes of Shah Waliullah of Dehli – were questioning the validity of the verses of the Holy Quran, liberal and moderate Muslim scholars saw it as a licence for drawing freestyle, innovative interpretations from the Quranic text.

Whatever the intentions, the objective seems to have remained the defence of Islam in the face of a storm that had whirled past the shores and was heading steadily towards the poorhouse of Indian Islam. The likes of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan rushed to find ways of proving that Islam was compatible with Western thought, science and philosophy in particular.

In such confusion, where distinguishing Islamic theory and practice from un-Islamic ones was based on opinion, everything simultaneously seemed right and wrong. This situation called for a judgement that could transcend opinion and declare what was Islamic and what was not; what was right and what was wrong.

This, however, was not possible without divine intervention. As Islamic theology turned into a hodgepodge, it was only God who could put everything back together by revealing what his faith actually meant in the face of modern challenges.

Such was the atmosphere of Islam when Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas wrote Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya.

Unlocking the door of divine revelation

As discussed above, Western philosophical movements and science had gradually taken the reins of the intellectual world. Sensory perception and pure reason had become the pivot of epistemology. Anything that failed the test was classified as “nothing”. How well-versed Hazrat Mirza Sahibas was with the intellectual trends of his time leaves his reader in amazement.

This understanding of modern intellectual trends is evident right from the very start of the very first part of Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya; the huge bulk of his works that followed over the years further testifies to it.

Hazrat Mirza Sahibas did not deny the importance of sensory sources of knowledge, but went on to prove that:

“If the testimony of reason relates to perceptible objects that can be seen, heard, smelled or touched, the ally that helps it reach the stage of certainty is called observation or experience. If the testimony of reason relates to events that happen or have happened in various ages and places, it finds another ally in the form of historical books, writings, letters and other records, which, like observation, bring clarity to the hazy light of reason, such that only a fool or madman will doubt them.

“If the testimony of reason relates to metaphysical phenomena, which we can not see with our eyes, hear with our ears, touch with our hands, or substantiate through historical records, then a third ally comes to the aid of reason. This is known as divine revelation.” (Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, Part 2, Tilford: Islam International Publications Ltd., p. 93; henceforth referred to by the part and page number alone)

Knowledge acquired through reason was thus analysed:

“Besides, I have already explained in detail that the recognition of God by the Brahmu Samajists, which is based only upon rational arguments, is limited to ‘ought to be’ and that they fall short of the perfect stage of ‘is’. The present discussion also shows that the clear and open path of the cognition of Allah is discovered only through the Word of Allah and cannot be reached or attained by any other means.” (Part 3, pp. 117-118)

Where Muslim scholars were relying on rational arguments alone and saw no other way than to impose their own opinion on the questioning Muslims; where Muslims had turned against Muslims owing to the rationalisation of Islam; where the obsession with pure reason had rendered religion a nonissue; Hazrat Mirza Sahibas, through Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, opened a new avenue of epistemology by introducing divine revelation as the strongest source of all knowledge.

This contribution takes Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya to a high station not only in religious debate, but also in the discourse of epistemology.

A challenge to all faiths

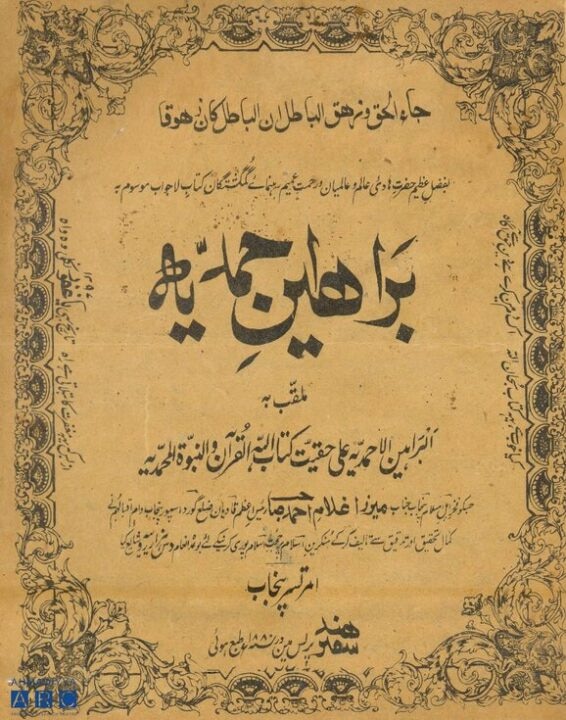

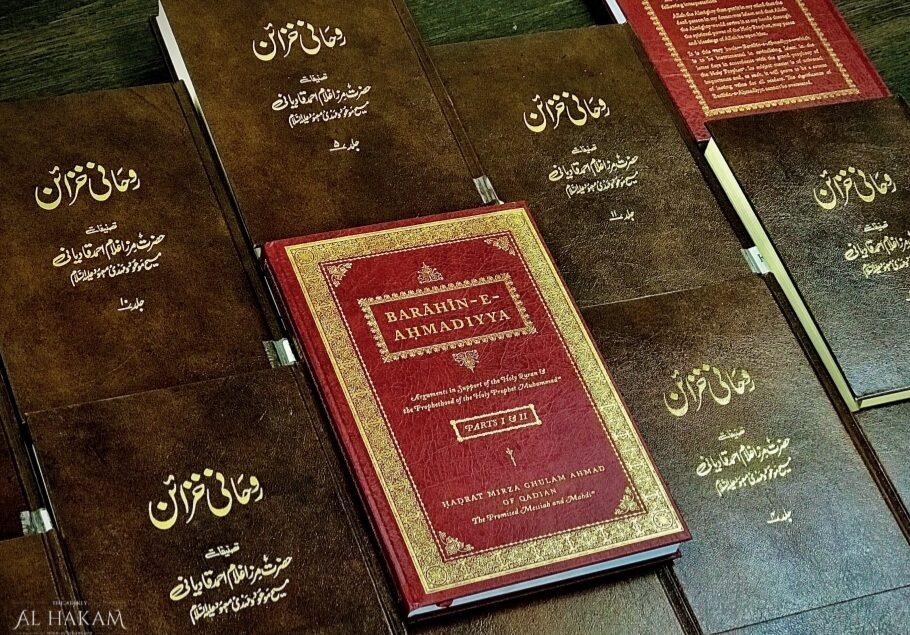

This work, commonly known as Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, was named in full by the Promised Messiahas as:

Al-Barahin Al-Ahmadiyyah ‘ala Haqiqati Kitabillahi l-Qur’an wa n-Nubuwwati l-Muhammadiyyah (Arguments in favour of the Holy Quran and the Prophethood of Muhammadsa)

This shows that the objective behind writing this book was not only to prove other religions, in their current state, to be misled and misleading, but also to fight off the challenge of Westernisation, before the current of whichall religions were on their knees.

He points to this danger at the very start of the book:

“If Muslim scholars—who are valiantly and vigorously debating with every disbeliever and atheist—were to give up this service to Islam, all the important traditions of Islam would soon disappear; instead of the traditional salutation [Assalamu ‘alaikum wa rahmatullahe wa barakatuhu], one would only hear ‘goodbye’ and ‘good morning’.” (Part 1, pp. 8-9)

The impetus and importance of this book are described at the very beginning, where the Promised Messiahas acknowledges the fact that a plethora of works of literature had been written, but they were addressed to followers of one religion or another.

“No matter how great or scholarly those books may be, they serve only the people to whom they have been addressed. This book, on the other hand, proves the divine origin of Islam and the superiority of the teachings of Islam over all faiths and establishes the authenticity of the Holy Quran through a comprehensive enquiry.” (Part 1, p. 9)

He further stated:

“This is why a book was urgently required to demonstrate, through rational arguments, the authenticity and divine origin of Islam in a manner that convinces all the other faiths.” (Part 1, p. 10)

What is called a gap area in the field of research – filled in by the works of researchers – emerge in religions over a certain period of time. The latter can only be filled through divine intervention. Such a unique gap, or gulf rather, had emerged in the mainland of religion and had to be filled with a unique work of Islamic understanding. As Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya aimed at defending the very entity of religion, it was done by defending the Quran and Islam, taking into account the Islamic belief that all religions were evolutionary stages of Islam.

Such a bold step was taken and a monetary challenge of ten-thousand rupees was offered to adherents of all other faiths. It was open for everyone and anyone to refute any argument presented in Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya from their own scripture and win the ten-thousand-rupee prize.

Although the scope of this article is not to address allegations, we might as well look at one as we go. Opponents of the Promised Messiahas ask why the font size of almost 25 pages in the first part of Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya is unreasonably huge – such that it allows only seven lines per page.

We would like to ask them in return to provide a parallel of such a bold challenge issued by any other scholar or leader working for the defence of Islam against not only other faiths, but also irreligiousness. The challenge was extraordinary, and hence, required extraordinary attention.

Even more amazing is the fact that the Promised Messiahas leaves the challenge open till the end of this world by saying the adherents of other faiths “shall not be able to face it until the day of judgement”.

As long as the challenge lies unaccepted, we take Barahain-e-Ahmadiyya to be a book of unique worth and value, not only in the history of Islamic literature but for the times to come too.

Disbelief: A by-product of pure reason

We have discussed above that as the Promised Messiahas embarked upon the task of writing this book, many objected to it and thought that there was enough literature to do the job. The Promised Messiahas addressed this question in part two of Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya:

“With even a little reflection, our critics will realize that the forms of corruption that have presently engulfed the world have no parallel in history. Whereas people in the past mostly fell prey to blind following, the danger we face today is the misuse of reason. Whereas people of the earlier ages were corrupted by senselessly following irrational ideas, they are now being led astray by false reasoning and logic. This is why pious and eminent scholars of the past did not have to employ the kind of arguments and reasoning that we have to employ today.

“The new light of our age (woe if this be light) is vitiating the spirituality of the newly educated. Instead of glorifying God, they glorify themselves; instead of following His guidance, they take themselves to be the guides. Today’s youth are generally inclined towards finding rational explanations and causes for all things, but on account of insufficient knowledge and wisdom, they end up being led astray rather than being guided.” (Part 2, p. 78)

Thus, the rationale for writing Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya was explained by the author himself: An obsession with pure reason, born out of Western philosophical trends, had spread its mighty wings to the extent that religion was now under its shadow. The situation was a never-before-seen one, and the solution had to be of a similar magnitude.

Seeing Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya as a response to the fast-spreading irreligious ideologies makes it a work of high stature. If it failed to defend Islam, and religion as an institution for that matter, it would be taken as a miserable failure altogether. There must be a test to see what this book actually did. We try a few below.

A study in Sociolinguistics

One of the scientific theories to blow air into the sails of atheism is the Darwinian theory of evolution. Charles Darwin presented this theory in his work “Origins of Species” in 1859. The Darwinian Man had evolved through various stages of being an ape through becoming human, hence throwing out the window the Biblical theory of the creation of Adam – a theory also testified to by the Holy Quran. This not only shook the Church to its core, but also the institution of religion altogether.

As for the Holy Quran, this theory could be lethal to not only its doctrine of creation but also to the Quranic epistemology. If the ancestors of mankind were apes, what was to become of the Quranic claim of وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الاَسْماءَ کُلَّھَا, meaning “And We taught Adam all names”? (Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.32)

If this Quranic claim were to be rendered meaningless through Darwin’s theory, it would naturally mean the falling apart of Quranic creationism and, consequently, of the very existence of God, the Creator.

Hence, the emergence of human language becomes an important question and brings to the surface an important debate about linguistic philosophy, tributaries of which lead into the question of the existence of God.

Noam Chomsky, the champion of modern-day linguistic philosophy, is a proponent of the Darwinian theory of evolution but also admits that language is an element that is unique to humans and that no trace of it can be found in other species of the animal kingdom. He also sees this as a gulf between Man and other species that might never be bridged. (Noam Chomsky, Language and Mind, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1968)

Richard Dawkins, a flagbearer of modern atheism, is also perplexed about the origins of human language (Unweaving the Rainbow, 1998), as is Terence Deacon (The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain, 1997).

The Promised Messiahas resolves the issue thus:

“Some people have fallen prey to the delusion that language is a human invention.” (Part 4, p. 15)

“Someone may say in support of this notion [i.e. languages have been invented by man] that we ourselves observe that languages are constantly undergoing hundreds of natural changes and alterations, from which it is proven that Man is involved in the changes. It should be borne in mind that this idea is a serious misconception. It is not through human intention or volition that languages change, nor can any law be laid down which establishes that human nature causes a language to change at certain times. On the contrary, careful study shows that all changes in language—as indeed in all things celestial or terrestrial—only come about through the special will and power of the Cause of all causes [i.e. Allah].

“It can never be established that mankind, jointly or severally, invented all the languages that are spoken in the world. If anyone harbours the doubt that, as God Almighty always causes languages to change through a natural process, why is it not possible that languages may have originated in the same way in the beginning without any particular revelation, then the reply is that the general law of nature at the beginning of the universe was that God created everything solely through His omnipotence. Reflection upon the heavens, earth, sun, moon, and on human nature itself would reveal that the beginning of time was the age of the manifestation of pure divine power, in which the usual [physical] means were not involved at all. Whatever God created in that age was done with such a magnificent omnipotence that it astonishes the human mind. Observe the celestial bodies—the earth, the heavens, the sun, the moon, etc.—how this immense task was accomplished without resorting to any means, builders, or labourers, solely by His will and a single command.

“Hence, when, at the time of creation, all things were initially brought about by divine command, and were caused by divine will without any involvement of natural causes and physical means, why then should we think, like the disbelievers, that God was incapable of creating languages even though He created everything else solely through His power? He who proved His perfect powers by creating Man without the agency of parents, why should His power be regarded inadequate in the matter of languages?” (Part 4, pp. 16-17)

The Promised Messiahas addressed issues that were to later become focal in the discipline of Sociolinguistics:

“The thought may cross someone’s mind as to why God does not reveal the knowledge of languages to present-day savages who have to make do with gestures, and why a newborn child who is left in the wilderness is not granted any revelation. Such thoughts result from a misconception regarding divine attributes. Inspiration and revelation is not a phenomenon that can occur gratuitously, without taking into account the potential required of the recipient. Requisite potential is, in fact, an absolutely necessary condition for divine inspiration and revelation. The second condition is that there must exist a real need for the revelation.

“In the beginning, when God created man, teaching languages through revelation was a matter that fulfilled both of these conditions. Firstly, the first Man possessed the requisite ability to receive revelation— as should have been the case. Secondly, there existed a genuine need that demanded revelation. For, at that time, Adam had no kind friend, except God Almighty, who could have taught him to speak and could have, through His teaching, made him attain the level of decency and civility. In fact, it was God Almighty alone who fulfilled all the essential needs of Adam and, by educating him in good morals and by cultivating in him good manners, exalted him to the rank of a true human being.” (Part 4, pp. 19-20)

It is interesting to note that Sociolinguistics was recognised as a discipline much later, after the time of the Promised Messiahas. (For details, see Sociolinguistics in India by Thomas Callan Hodson, first published in 1939)

After a healthy and rich debate on Sociolinguistics, the Promised Messiahas concluded it as follows:

“The knowledge of language itself comes from God. It was He who taught us individual letters and words. They are not the invention of Man’s mind. The only thing that Man invents is the use of those words in various combinations.” (Part 3, p. 37)

The use of words in meaningful combinations, referred to by the Promised Messiahas, is known as syntax in linguistics. Linguistic scientists and philosophers, after decades of experimenting, have now come to agree that no animal, including the alleged ancestor of humankind, has shown any sign of ability to learn language, owing to its inability to create meaningful words – not to speak of syntax. (For details, see Babel’s Cornerstone by Derek Bickerton)

This conclusion, drawn by modern scientists and linguistic philosophers, bears testimony to the unique argument given by the Promised Messiahas for the existence of God. His argument spans beyond sociolinguistics and opens new avenues for creationist/evolutionist discussions.

While we wait for someone to bring an example of such scholarship – as the one presented by Hazrat Mirza Sahibas – from those turbulent times of Islam, we will continue to proudly present Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya as one of its kind, and with no parallel.

Modern debates in Psychology

They say that three theories have shaken the modern world: the Copernican model of the heliocentric galaxy, the Darwinian theory of evolution, and the Freudian theory of psychoanalysis.

Having dealt with Darwin, we now take a look at the ground-breaking theory of Sigmund Freud.

Freud is credited, and rightly so, for having changed the direction of psychological studies by proving that the human mind is controlled primarily not by the conscious mind, but by its unconscious vault – where lies the key to human personality. He proved that it was delving into the depths of the unconscious mind that could help understand and manage neuroses and various forms of psychoses.

Freud’s work on the unconscious mind took shape between 1900 and 1905, where he presented the human mind as an iceberg – a tiny bit above the surface, the gigantic mass below: The hummock (the part above the surface of water) manifests what is actually stored in the bummock (the part submerged in water). It is the bummock, or the unconscious mind in Freudian analogy, that remains of focal value.

Before moving on, it is important to understand the etymology of the term “psychology”. A combination of Psyche and Logos – Greek words for “soul” and “study” respectively – the collective term means “study of the soul”.

Like God, the soul too had failed modernity’s test of sensory experience and, hence, was seen as a redundant concept with no link to reality. Yet, we see that one of the vital issues in the modern world is mental health, gulping up billions of dollars in research and treatment. Never before was mental health such an excruciating problem as it is in modern times.

We now go back to the time of the Promised Messiahas, two decades before Freud’s model of the human mind came out. Huzooras, in Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, presents two parallel systems: one of the human body, the other of the soul attached to it:

“It should be borne in mind that God has created certain remedies for physical illnesses and has brought into the world excellent things like antidotes, and so on for diverse types of pains and disorders and has invested these remedies from the beginning with the characteristic that when a diseased person, whose illness has not gone beyond remedy, uses these medicines with proper care, the Absolute Healer bestows, to some degree, health and strength upon the patient according to his capacity and ability, or restores him fully to health. Likewise, God Almighty has, from eternity, invested the pure spirits of these accepted ones with the characteristic that their attention, prayers, companionship and high resolve are the remedy for spiritual ills. Their souls become the recipients of diverse types of grace through visions and converse with the Divine, and then, all that grace manifests a grand effect for the guidance of mankind. In short, these men of God are a mercy for the creatures of God. As it is the divine law of nature in this world of cause and effect that a thirsty one slakes his thirst by drinking water, and a hungry one satisfies the pangs of hunger by eating food; in the same way, by Divine Law, Prophets and their perfect followers become the ways and means of healing spiritual ills. Hearts obtain satisfaction in their company, impurities of human nature begin to recede, darknesses of the ego are lifted, zeal of love for the Divine surges, and heavenly blessings manifest their splendour. Without them, none of this can be achieved, and these are their special signs by which they are recognized.” (Part 3, pp. 253-254)

The mind-body relationship has remained a favourite issue in philosophy and psychology. In philosophical and psychological terms, the issue is all about identifying the link between the body and the soul, or the mind as the two would like to call the latter.

Behaviourists seek the solution to psychological problems through, as their name suggests, whatever becomes manifest in the form of thoughts and actions. The dualists, on the other hand, see the mind and body as separate entities, albeit as having the ability to influence each other. However, all such discussions emerged long after the time of Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya.

The Promised Messiahas saw them as two distinct, separate entities and highlighted the importance of the soul:

“Leaving aside matters of greater profundity, reason is perplexed at the very first step—what the soul is, how it enters [the body], and how it departs. On the face of it, nothing is seen as departing or entering. Even if you were to enclose a living being at the time of its last breath inside a glass chamber, nothing would be seen departing from it. Similarly, if germs are produced in some matter that is enclosed within a glass chamber, one cannot discern the path of entry of these souls.” (Part 4, p. 81)

We must remember that the Promised Messiahas was not writing a book on psychology. Nor was Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya intended to be a book of scientific inquiry. Huzooras was proving the supremacy of Islam over all Man-made intellectual disciplines. He was, however, acquainted with debates in the modern intellectual world which seemed to remain in his stream of thought. His aim always persistently remained proving the existence of God – non-existence of Whom had led to the vices of the modern world. He stated:

“The egg is even more astonishing as to how the soul flies into it, and if the chick dies inside, by what way does the soul escape? Can any wise person resolve this puzzle through the use of his intellect alone? You may run wild with your conjectures as much as you want, but nothing actual and certain can be established through reason alone.

“That being the case at the very first step, what can this defective reason discover with certainty about the matters related to Hereafter?” (Part 4, p. 81)

As if he saw what tumultuous times awaited the mental health of humankind in future, he wrote:

“Alas! Why do you not understand that it is impossible to find a remedy for every anxiety of the soul and to treat every malady of nafs-e-ammarah through self-conceived imagination and conceptions?

“It is the law of nature that when a man is overpowered by some carnal desire or is subjected to a spiritual calamity—for instance, when his anger is fuelled, or his sexual desires are aroused, or he runs into some trouble, or he is in mourning, or is stricken with grief and a painful situation, or has been overcome by some carnal or spiritual disturbance— he cannot cure his maladies and motives that have taken control over both his mind and soul, merely through his self-admonition and advice. Rather, to remove such passions, he is in need of a counsellor who commands the respect of the listener, is venerable, truthful in his speech, perfect in his knowledge, and trustworthy of fulfilling his promises; and furthermore, has the power to achieve that which inspires awe, hope, or comfort in the listener’s heart.” (Part 4, pp. 81-82)

Having highlighted the fact that the fast-paced modern technological advancement – shunting everything to do with the soul – might bring physical ease and convenience, he went on to explain that it could deeply injure the soul. As if addressing psychologists, he stated:

“All of these matters are such that a wise man would himself admit that he needs them when he finds himself in a situation of being overpowered by his ego and afflicted with anxiety. Rather, those whose souls are highly refined, seekers after truth, and those whose hearts are disgusted at the very onset of the turbidity and sordidness of sin, implore like a sick man for such treatment themselves when they are in situations where they are overpowered by their egos, so that they might be cured of their internal constriction by hearing some words of inspiration or warning, or by listening to some words of satisfaction and comfort flowing from the tongue of some man of God.” (Part 4, p. 82)

Hence, Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya is a marvellous work in that it drew the attention of the modern world towards vital issues of human psychology. Where psychologists reached the point that all mental disturbances have roots in the unconscious mind, the Promised Messiahas guided them through the massive balls of tangled wool that lie therein, and also through untangling them.

Huzooras said that “Man’s wonderful soul has been fashioned for the complete cognition of God.” (Part 3, p. 140)

This serves as a great indication towards resolving mental health issues of our day and age.

Conclusion

A lot has been written about the immense contribution of Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya to Islamic literature and a lot more will be written. This article was only a sneak peek into the marvels and treasures that lie therein. Lest bias prevail, I conclude with the words of Wilfred Cantwell Smith, who stated the following about the Promised Messiah’sas work:

“It arose as a protest against Christianity and the success of Christian proselytization; a protest also against Sir Sayyid’s rationalism and Westernization, and at the same time as a protest against the decadence of the prevailing Islam.” (Modern Islam in India, A Social Analysis, 1943, p. 324)